We bring in two experts to discuss. Scott Tranter currently leads data science and engineering efforts at Dynata. He’s also the co-founder of Optimist Analytics, which was acquired by Dynata in 2021, and is an investor in Decision Desk HQ, which provides election results data to news outlets, political campaigns, and businesses. We also have with us professor Katharine Donato, who holds the Donald G. Herzberg chair in international migration at Georgetown University, and is the director of the Institute for the study of International Migration in the Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University.

Xiao-Li Meng: Katherine and Scott, thank you so much for joining us. Since this is a data science podcast, the first question is about data. What are the current reliable opinion polls available out there about the general American public sentiment toward refugees and migrants, and how do we know these opinion polls are reliable?

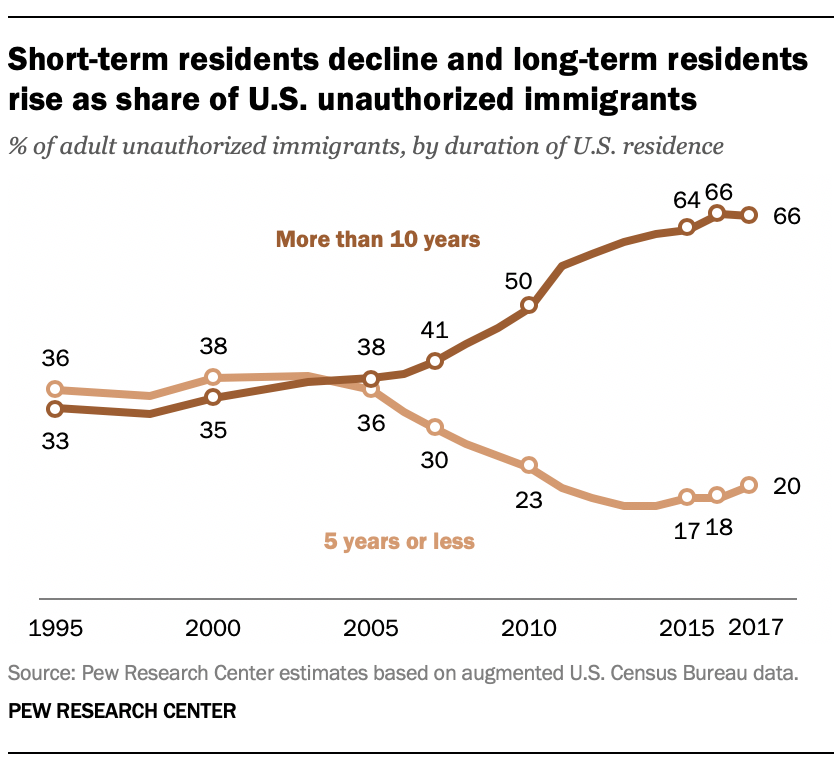

Scott Tranter: Let me break that down into two questions: What are good ones, and how do we know they’re reliable? I still think Pew is probably the best resource for what I would call unbiased research on the American public opinion. They do a very good international public opinion as well on immigration issues and things like that. One of the reasons is that it’s very longitudinal. They have some questions on immigration going back 30, 40, 50 years now, probably even longer than that. And they’re very good and well-funded. They don’t miss quarters. They don’t miss reportings. And so we can look back at the 90s, of what people thought about cross-border immigration between U.S. and Mexico, and see how it’s evolved over the last 20 years as debate. How do we know it’s reliable? That’s the ever-pressing question with polling: Is it reliable?

And I think, Xiao-Li — you and I have talked many times. It’s statistics. We’re getting close, but we’re probably wrong somewhere. And the key is to know where we’re wrong. That’s a long way of me saying I think Pew does a good job because they’re consistent. They may be wrong, but they’re looking at attitudinal shifts and if they’re off by five, they’ve been off by five for 30 years and they get us right directionally, which I think is the important part when people look at polls. Don’t look at the numbers and look for precision, look at the numbers and look for trends. And I think that’s what everyone should take away from stuff like that.

Xiao-Li Meng: And this is a question for both of you. You both talk about this, the importance of thinking about things over time. As we know, the public tends to pay particular attention to issues like refugee migrants during times of crisis. Whether it’s Syria, Venezuela, now it’s Ukraine. How have things changed over time?

Scott Tranter: I think when we look at some of the polling in and around some of these countries before they become in the news — you mentioned Syria, you mentioned Ukraine. The southern border, while it is persistent in U.S. politics, has times of spiking and not spiking. It’s largely changed when we look at the U.S.-based stuff, it’s largely revolved around political party lines. And the messaging has roughly been the same over the last 10 or 15 years. It’s not necessarily about the specific reason it popped up. During the 2020 election, it was around some of these migrant caravans coming from South America up through Mexico, across the border. It really wasn’t about that specific caravan, while that’s what the news covered. That was symbolic of the larger immigration issue as a whole. Whereas we see internationally when it’s about Syria, or Ukraine, it’s usually not about that specific instance.

It’s about, what do we think about foreign aid? All of a sudden the public remembers that we spend billions of dollars on foreign aid. It’s not hundreds of millions of dollars, things like that. That’s been primarily how the public has been viewing it over the last 10 or 15 years, mostly because of how they are consuming their news and where they get their news from. I think what’s interesting or what I’ve noticed has changed is there isn’t a whole lot of movement, and I’d be curious to see what Katharine thinks on this in general — feelings about, should we support refugees overseas or by and large, should we support change to our immigration policy in the U.S.? The opinion lines have been pretty solidified, which is interesting because we do know from public opinion research and sociology and political science that you can change people’s opinions.

These things happen quite a bit. And I think there’s an opportunity here for people who want to push their side to change up the messaging a little bit to get what they want, because we do see that in small-scale tests, whether it be message testing, ad testing, or focus groups. There’s quite a bit of consistency. There’s not a whole lot of change over the last 10 or 12 years in the messaging or what we’ve noticed in opinion, but it doesn’t mean it can’t change in the future.

Katharine Donato: I do think you bring up an important point, which is that as we think about countries to the south of our border at this point, really not Mexico, as much as northern, central America. The story that’s told in the U.S. is very politicized. And actually, that goes back 30 years. Thirty years of one party viewing the border and viewing the issue in one way versus another. But that view is very different than what’s believed with respect to Ukraine, with respect to Syria, with respect to Afghanistan. And because that story of refugees who come from those places come from a situation of international import, international aid and international relationships. The entire country was following the Afghan evacuation in August. I think primarily because we had been — we as a country and so many Americans had made relationships and understood the real life experience in Afghanistan and understood people and said, “We really have to do something. We have spent decades in this country and we really need to get these people out.”

We, in theory, could have that same opinion about Honduras, but we don’t, and that’s partly because the politics and the messaging around the countries south of the border has never been the same kind of messaging that recently we’ve seen with Afghanistan and Ukraine. And you could argue that kind of messaging doesn’t exist for smaller scale movements of people who are forced to move.

Think about the Rohingya in Bangladesh. That was certainly forced movement, but it wasn’t about international relationships between the United States and other countries. It wasn’t about international aid. And there still are over 700,000 people from Myanmar living in Bangladesh with I don’t know what kind of future there and more and more kids being born stateless because Bangladesh isn’t giving them birth certificates. These sorts of situations when they’re not part of foreign aid and foreign assistance really just sit and fuel other issues that are problematic over time.

Liberty Vittert: I do have a question about these movements of people. Something like the Afghanistan crisis. It was a very easy thing for someone to wrap their head around. These people helped us. The Taliban’s now coming to kill them. If we don’t get them out, they’re going to be killed. That’s a very easy thing for me to understand. Whereas with something like the southern border, when I was recently there, I met people who had been forced out of Honduras because the government was trying to kill them, but I also met a family who was coming up because the father simply couldn’t find a job, but it wasn’t like the government was coming to try to kill him. I can understand how there’s confusion between those two types of people specifically for Americans. Is there real data on how many people are coming from our southern border that are what you would normally think of as a refugee, like the Afghanistan crisis versus people who are coming for other valid reasons, but not necessarily for refugee status?

Katharine Donato: Let me say this: Reasons and motives are messy. Every time I go to either border — the U.S. southern border, the Mexican southern border, doesn’t matter — people tell you all kinds of things. Let me step back by saying, in response, that you can wrap your head around the idea — and most Americans did that. We worked with these people for 20 years in Afghanistan. And so many of them now, as the Taliban takes over, are going to be at risk and we owe it to them and our country to move these people out and give them a place for them to raise their children in a peaceful way. But migration from northern central American countries started growing in the late 80s. It took off in the 1990s. There was essentially no migration from northern central America before the mid-1980s.

And then 20 years later, we’re wondering why there are so many children at the border. Those kids are trying to reunite with their parents who are in the U.S.

What I don’t understand is why we can’t wrap our heads around the fact that we, the United States, has been relying on the labor of immigrants from northern central America and from Mexico for decades. And then we’re surprised that when the kids get to be 13, 14, 15, they want to live with their parents?

Back in 2014, I was saying this. Why aren’t we helping evacuate those kids to go to the U.S. in a legal, safe way versus what has happened?

Which is they hire smugglers and come up to the border. To me, that’s a very simple thing that people could get their heads around, but there’s a lot of resistance to recognizing how much we in the U.S., our lives are subsidized by the lives of immigrant laborers. We do as a nation and as an economy rely on immigrant labor and yet we can’t wrap our arms around the fact that there could be kids and grandkids who want to reunify after years of living without their parents. These kids want to reunify with them here.

Liberty Vittert: It’s funny, I wrote an article using a lot of data about how we need to increase immigration or risk economic disaster for the United States, but I’m totally with you. And it makes so much sense. I can’t help but wonder though, is there a difference in the way Americans feel versus Europeans? Scott, is there any data on this: Are Europeans more willing to accept immigrants or is the U.S. more willing to accept immigrants? I think with news messaging, I always imagine that America’s the most closed off, but maybe it’s not. Do we have any feelings about this or knowledge about this?

Scott Tranter: It’s funny you bring that up, because I always talk about it. Let me bring up one extreme example. You look at the country of India and how much immigration they allow. Naturalized immigration. I think it’s in the low four digits. A country with over —

Liberty Vittert: What? You mean like 1,000 people?

Scott Tranter: Yes. Naturalized. They allow guest workers and things like that, but they’re just like, “No, we’re not going to naturalize someone from Canada who wants to move to India.” And I think we see that a lot. I’m using an extreme example there, but let’s take a look at the Syria refugee crisis. And a lot of those folks were moving through Eastern and Western Europe. And you would see in places like France, especially the suburbs of Paris, lots of riots, lots of opinions and lots of, to be honest, racism against Syrian immigrants as they came through. You see this in Germany, you see this in Hungary. You see this in Poland. You saw this in Ukraine, too. Immigration is a huge issue in Europe and it’s highly polarizing. And I would argue in some instances more polarizing than it is in the U.S. because I think they have a little bit more in-your-face protests about it and things like that.

But the U.S. is by no means the worst and by no means the best if your measurement in worst and best is acceptance of immigrants. It’s a big issue everywhere. What’s interesting is the rhetoric and some of the opinion and messaging around it. In the U.S. in the early 2000s, the messaging was always, we don’t need immigration because we’d like the Americans in the job. Over the last five or six years with unemployment sitting somewhere between 3 and 5 percent, which is historically low, that’s a harder message to do. But in places like France, where you will see unemployment, especially in regions, at 10 to 15 percent, that’s still a pretty potent argument. And it’s one of those things I think internationally is an issue. Enlightened might be the wrong word, but I don’t necessarily think our European friends are looking at immigration any better or worse than we are. They’re looking at it with similar problems and on similar scale.

Katharine Donato: I totally agree that it’s not the worst here. We do have a system to naturalize and you can set yourself up to naturalize after getting permanent residency. It takes time. It’s an investment, but it can be done. And in many parts of the world, no one can be naturalized, or as Scott said, very, very few people can be naturalized. There’s a long history of many European countries not allowing citizens to be foreign nationals. But even during periods of tight restrictions, there are still foreign nationals who are permitted to live in the U.S. permanently and to be naturalized. I talk about all the problems in the U.S. system and at the same time recognize that we are in one of the nations that along the lines of citizenship and some other factors has a pretty good track record. I’d love to hear Scott talk about the border for people who don’t know much about the border and many people in the U.S. — and if we just think about the southern border, many people in the U.S. and in Mexico really know very little about the border.

The border is a really unique, specific place, physically, and economically with respect to the movement of people. And yet when it comes to the politics around the border and the political opinion around the border, in the minds of many, they equate the border to migration. When in fact the border is so much more than that. I think if we were able — we, the big broader U.S. — if we were able to see the border as more than migration, we actually could do some really good things that would strengthen that regional border place, which for me is typically 20 to 40 miles from the border north and south. And we could strengthen it in so many ways that would make it a better place for everyone there.

Scott Tranter: I know we’re on the data podcast, so I will bring in a qualitative focus group I was in. It was interesting. We’re in Minnesota and you’re asking people about what the border meant to them. So Minnesota, right, they have the Canadian border, but they’re pretty far away from the southern border. And they had some pretty strong opinions about how the border affected their day-to-day life. Think about that. They think the U.S. southern border affects their day-to-day life and they might make an argument… They might say, “We need a strong southern border because I want trucks to pass through freely so I get goods better.” They might make an economic argument, or et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. But no, they were making a safety and fairness argument.

And the safety and fairness argument was — first, they’re like, “An unprotected border lets in a lot of people we may or may not like, whether they be criminals or terrorists” or whatever it is. So there’s an aspect there. And a fairness is, “it’s not that we don’t like them, it’s just why do they get to cut the line?” And for them, the border is symbolic of those two things. And if we sat in focus groups, and I’m sure there have been some poll questions constructed, although they’d probably be pretty poorly constructed poll questions that ask at that… Generally speaking, I would say if you’re asking it within 30 or 40 miles of the border, you’ll probably get a better answer. But if you’re asking it anywhere in America, the border pretty much is equated with fairness and safety and things like that, whether that’s true or not.

And I think that is just the easy answer for folks. And that’s what has been drilled in for the last 15 or 20 years with 30-second ads and 10-second flashes and 10-minute fiery speeches. And it’s one of those things I think we need to get off the sound bites — and a little bit that’s the public. I blame the public for this — we’re just people of convenience, and I don’t really want to think about this much longer than the 15 seconds that’s in front of me. That’s the answer in all public opinion. If we are doing this on climate change and how to educate people on that, it really boils down to, we have got to stop speaking in 15-second increments. If we ask the border question of some very staunch Republicans who own hundreds of acres on the U.S.-Mexican border, they’re actually fairly pro-immigration as far as it goes in the political spectrum. They vote Republican every single time and they own property on the border and they own guns and all the other things.

But they’re like, “Look, unless you’re going to put a hundred-foot fence up and then man someone every 10 feet, the wall isn’t an answer. We have to have a comprehensive… We have to have a way to get it. And oh, by the way, I want some of these workers to work on my farm and they want to work on my farm and then they want to go work somewhere else.” And I think, the closer you get to the issue, the more educated people get. It’s just because they have to spend more than two minutes on it.

Liberty Vittert: We can say, what is the general American public feeling or we can say, what is the general international feeling towards the refugees or immigrant movements, but how does it break down? If we’re actually trying… If political parties either direction, or if organizations — nonprofits — are trying to sway American public opinion one way or the other in terms of how they feel about refugees and migrants, who is it that they need to sway? Who feels which way? And what is the kind of messaging that works? What can actually make someone feel better? Scott, I remember USA for UNHCR did some work. And there were things that surprised me that actually swayed people negatively, gave people less affinity for the cause. That surprised me. How do we figure those things out?

Scott Tranter: I think public opinion polling is important, but I think we also need to go upstream with some of the message testing and how we present this information. And let me give you a parallel. When looking at trying to convince people about climate change, what a lot of organizations found was that we don’t talk about the scary parts of climate change, we talk about if the sea is going to rise, then your flood insurance is going to get higher. That actually happened to convince a lot of people who are like, “I don’t know, climate change may be a thing, may not be a thing, but if you’re telling me my home insurance is going to go up, my flood insurance is going to go up, I’m going to start paying attention to this.” If we take that example to immigration, maybe we don’t talk about some of the hard… It could go either way. Maybe we don’t talk about some of the hard economic choices. We talk about the moral choices. And then we see things like the Catholic church specifically in the U.S., they’re considered relatively pro-immigration and that’s the angle they go, and they seem to have some efficacy there. Or on the flip side, I’ve seen some testing on some ads where people crossing the border, they’re going to be here, whether or not you think they should be here or not. So they should be in the system so they can be contributors and they can not be in the shadows of society. That’s reason and logic. And that’s a long way of me saying there are a lot of different ways to do it and different pockets of people respond differently but what we really need to do is take the one step beyond the public opinion and really start message testing this and seeing what different groups it goes against.

Katharine Donato: And I would say the message testing has to be not done at one point in time only because we do live in this very dynamic political landscape at the moment. A dynamic, let’s say, just in the last 10 years, if we think about politics. We need to be able to do that message testing, make a commitment to do it over a period of years and different months in a year so that we can really figure out whether or not something is specific to a particular time and place, or whether it truly can make a difference across, let’s say, much of one country over a period of a few years.

Xiao-Li Meng: Speaking of informing the public and educating the public, having longer conversations to make sure everybody understands what things really are… There’s one thing that has changed over the time and is increasing becoming a concern for all of us — and Katharine, thank you for your wonderful article for Harvard Data Science Review about misinformation, that you wrote about how the trigger is misinformation about a set of announcements about entry and exit restriction at the Venezuela and the Columbian border. My general question here is, first, what do we know about the impact of this misinformation? As Scott just said, a 15-second ad can influence people’s thinking and 15 seconds of misinformation can probably do quite a bit of damage. And my second question probably is even a little bit harder: How do we make sure that particularly for the data science community itself, that when we study those issues, that we make sure we don’t fall into the trap — for example, select or study something that supports our ideology, because that can distort the information?

Katharine Donato: Let me say that the piece that I wrote for the journal, we looked at certain announcements and certain events, and then tried to… We used Twitter data to look at the conversation before and after those events and those announcements. And on the one hand, there is a lot of concern and we need to be concerned about misinformation and all the information that is not empirically supported, but on the other hand — and one of the events that we focused on was the president of Venezuela when he announced that there is a miracle drops cure to COVID. We were interested in seeing after that day, how much that messaging sustained itself. And for the first few days we saw in terms of frequency a lot of messaging, but the key finding is that messaging drops down to almost zero within the first two weeks of that announcement.

It wasn’t successful from Maduro’s point of view, I assume, or his people, because I’m assuming that they had hoped to make this announcement because they wanted other things to happen. And that the announcement itself just has no salience on Twitter by a month afterward. That gives me some hope that some forms of misinformation will not have the saliency that I would worry about. That I would worry about. And you can measure that by — in this case, we use Twitter, but you could also look at other forms of organic data that would help you, let’s say, from online newspapers and different languages. And you could look at any event or any announcement and try to understand whether or not a conversation about that event or announcement shifts over time. That’s interesting. That is something that before this age of social media, we couldn’t do. We did look at the conversation, but we didn’t have the same data. We didn’t have the same amount of data. We didn’t have all of the data analytics we have now.

On the one hand, we’re moving forward. On the other hand with all of the social media, we have certainly evidence of — I don’t know if it’s more or less; I fear that it’s more — misinformation and the ability for computers to create more of that misinformation on their own. Increasingly, in all areas of the social sciences, we move toward using these data more, absolutely. If we have a fabulously important question, we also have to prioritize the misinformation piece. What are we going to do to answer the question, to me now, is only half of the question that ultimately needs to be asked and answered because the other half has to be, how do we know what we’re seeing is real? And how do we understand the various forms of manipulating the messaging or the conversation that we’re studying?

Liberty Vittert: Professor, is there a specific example over the past X amount of years of a trend that really surprised you or that you think that people wouldn’t know about when it comes to sentiment?

Katharine Donato: I don’t know how much people know about it because you can’t really tell in this politicized environment we’re living in. I think a lot of people know this, but they don’t own it as knowledge that’s important, at least that’s my sense. I’m not a politician, but the fact that you have 80 percent or so, give or take, of the American public supporting DACA and supporting a way of making DACA become more permanent as a status — that’s the program that President Obama through executive action started in 2012. It just actually had its 10 year anniversary. DACA stands for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals and I think estimates are about 700,000+ people in the United States have DACA. It is not a legal status. It is a status and it’s temporary, but it does allow people who came in either with their parents or without their parents, as children, to move their status toward regularizing it so that they can work in the U.S. and they can be above the table versus below.

When you look at public opinion about DACA recipients, you just see very high numbers, a lot of support. And yet it’s 10 years old and we still have 700,000 or more people without a formal regularized status. And when I talk and I tell people about the support for DACA, sometimes people know. People on both sides of the political spectrum or on all sides will know there’s a lot of support for the DACA recipients. And yet at the same time, there’s been no change, no ability in Congress to move it forward. That’s just one of several examples I think. Generally, the U.S. public is in support of immigration and yet we hear so much more in the media about, let’s say, the problems on the immigration side. I don’t know if it’s just that people don’t know some of the findings about public opinion nationwide or they just don’t then own it to move some change forward.

Liberty Vittert: Given all of this misinformation, given all these conversations about refugees and migrants, Scott, you are the caller of the elections coming up in 2022 and 2024. How much will these conversations be affecting ‘22 and ‘24?

Scott Tranter: That’s always my favorite question, especially when we’re four months out. What I have been amazed about is the public’s ability to not have any attention span. And what I mean by that is whatever we’re talking about today, if we’re talking about it in the final four to two weeks, then maybe, but if we know what we’re going to be talking about in the final two to four weeks in October, we should all go start a political consultancy, because we will all be bajillionaires and pick the winner.

Liberty Vittert: We’ll go to Vegas and bet on the winner.

Scott Tranter: Vegas or the UK where you can actually bet on this stuff. The answer is that it’s possible, but politics doesn’t drive the news. Politics reacts to the news. And what does the news do? The news is very, what can I get attention on? If you tell me what we’re going to be talking about in October, I’ll tell you what the issues are, but I don’t think anyone can do that.

That’s a long way of me saying immigration is always going to be an issue on people’s radar if it’s polled. It is consistently polled on the top five of issues. It’s usually not the number one. Occasionally it gets number one. For instance, in 2008, it was number one in Arizona for the presidential. Why? Because John McCain ran on those types of things, but it is usually top five. And when I say top five, everyone could probably guess it’s big broad issues like immigration, healthcare, jobs, and economy. Sometimes you separate those out and then there’s usually some foreign affairs aspect or something like that. But those generally are what they are. Today, the number one issue, by and large, is inflation, which is a proxy for the economy.

Liberty Vittert: It’s the economy, stupid. Isn’t that the quote?

Scott Tranter: It’s the economy stupid. Yeah, James Carville and Paul Begala used to say that. It’s one of those things, and why is that important? It’s because gas in California is above seven bucks a gallon. That’s what they care about and that’s what’s on the news. And I don’t know if this will be an issue this fall. I do know that border issues, immigration issues are fundraising issues for both the Democrats and the Republicans. Even though it’s not maybe talked about in the news, it’s what a significant amount of Republican candidates use to their position on what they think should do with the border. They will raise millions if not tens of millions of dollars on their position. And so will Democrats, by the way. Democrats will also, off their immigration positioning, raise millions, if not tens of millions of dollars. It is an issue that resonates. Whether it’s an issue that moves the middle or moves the sway-able voters, that’s a different question. And I don’t have an answer for that, but it does move money among the opinion hardened left and right.

Xiao-Li Meng: Thank you, Katharine and Scott, for this really both informative and thought-provoking conversation. Unfortunately, we have to wrap up. But we always end with this magical wand question, and today’s question is, what data do you want? If you can wave your magical wand, what data do you want about refugees that you don’t have?

Katharine Donato: What I really want are detailed movement histories. And when I say detailed I don’t just want to know if you’ve moved because you were forced to move. I want to know when you moved, how long it took you to get to wherever you’ve gone, what’s happened in the place that you’ve been received and, importantly, if you’ve moved beyond that first move. We know very, very little about secondary and tertiary movements among forced migrants, whether they’re formally refugees embedded by the UNHCR or not. Remember that less than 1 percent of refugees get resettled. UNHCR vets people, gives people the refugee label following global protocols, and then most refugees remain refugees and can’t really leave where they are, but we don’t really know that. We just know that only 1 percent get resettled. What happens to everyone else and what happens even after you get resettled?

I would like to see migration history data that are timed that would allow us to understand the first, second, third moves of people. And then we could really tie such data, if they’re tied to time and place. We can then integrate other traditional data sources with them. We could certainly understand climate-induced migration and environmentally induced migration in a much deeper way than we have. We have some survey data that offer those kinds of detailed migration histories, but they’re very specific to place and certain migration circuits around the world. And none of the global multilateral organizations collect such data because they’re in the business of providing relief as well as some other things. They’re too busy, but I think we could make a really significant move forward if we had such data about people who were forced to move.

Xiao-Li Meng: Thank you. Scott?

Scott Tranter: In my answer, it’s going to be a little more specific. I would love… Specifically in the U.S., economic migration history. What I always wondered is if you’re a person who crosses the border, you walked 10, 15, 20, 30, 40 miles in an area I would never walk to a place where you’re not sure how you’re going to feed or shelter yourself. And then a lot of these people, by and large, are getting jobs and then they are working themselves up to pay for shelter or send their kids to school and things like that.

And I think if we had good economic data on what happens to these immigrants, especially in the U.S., on how they integrate themselves into society, I think that’d be much more enlightening and move us away from the anecdotes of, “They’re just coming here so they can rob a 7/11 or they’re just coming here so that they can walk into an emergency room and glum off healthcare.” I think if we had hard data, irrefutable data on what these people did once they came across — and not just 30 days after, but years after — I think we’d do away with the anecdotes and really bring some hard data to it.

Xiao-Li Meng: Wonderful. And both of you, I’ll just remind the whole data science community how hard it is in this humanitarian study to collect data. And I really want to thank both of you, but I also want to just again, make a plea to the general data science community through this podcast, that there is so much more can be done, should be done. And the data science community can help. And I think I keep using the words data science here in a broadest sense because lots of things here are really about even how to ask the question, what to measure, and in this geo-space, one of the hardest things about collecting data is that you will have countries, regimes that will actively conceal their data. This is another level of complication that I think really the whole data science community can help to work on. And, again, thanks to both of you for such a thought-provoking conversation, and thank you again for your time.

Liberty Vittert: Thank you both so much.