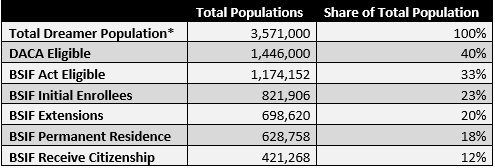

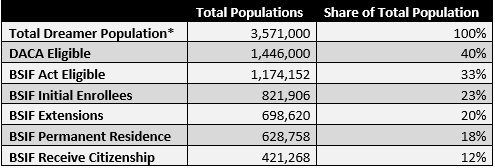

House Republicans will vote on their “compromise” immigration bill this week. Moderate Republican supporters of the bill may argue that its many restrictionist features—including draconian asylum provisions, cancelling the applications of 3 million people waiting to immigrate legally, and permanent reductions in legal immigration—are a small price to pay to help the entire Dreamer population gain a “pathway to citizenship.” However, an analysis of the Border Security and Immigration Reform Act (BSIF) shows that even under the most generous assumptions, the bill would likely initially legalize only 821,906 people, provide permanent residence (i.e. a pathway to citizenship) to 628,758, and result in citizenship for 421,268.

As provided in Table 1, only a third of the Dreamer population would likely receive status under the House plan (H.R. 6136), and just 18 percent would likely make it onto the pathway to citizenship. Only 12 percent would likely apply for and receive citizenship. Moreover, even the pathway to citizenship is tenuous, since—for all Dreamers in DACA or without legal status today—it is contingent on a future Congress appropriating money for a quite expensive (at least $25 billion) wall and security system along the Southwest border of the United States.

Table 1: Dreamer Populations and Eligibility Under Border Security and Immigration Reform Act

Sources: Authors’ calculations (see below) based on population estimates from Migration Policy Institute (DACA eligible and total Dreamer Population based on American Hope Act); Border Security and Immigration Reform Act (H.R. 6136)

*As of December 31, 2016

If Congress wants to help a larger number of Dreamers, then it would need to establish clear legalization criteria with lower costs and fewer risks, while providing greater legal certainty for the parents of Dreamers to mitigate fears of coming forward. Members of Congress should not exaggerate the extent of the legalization of Dreamers as a way to justify politically questionable policy choices, including reducing the annual level of legal immigration and eliminating several current immigration categories.

Restrictive Criteria in the House Bill

Back in January, President Trump promised a pathway to citizenship for Dreamers—up to 1.8 million of them. That’s still just half of the 3.6 million Dreamers—unauthorized immigrants who entered the country as minors—estimated by the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) to be in the United States as of January 1, 2017, but it’s still far more than the estimated number of Dreamers who will likely receive permanent residence under the House compromise legislation that will receive a vote this week.

The BSIF Act creates a four-part framework for potentially receiving permanent residence—a “path to citizenship”—and later citizenship (see Table 2 at the end). First, Dreamers would need to meet a set of basic criteria to receive conditional nonimmigrant status, a temporary renewable legal status. Second, after six years, most would need to apply for a renewal of this status. Third, they could apply for permanent residence over a 15-year period if they met a final set of requirements. Fourth, they could apply for citizenship five years after receiving permanent residence. Each stage will reduce the population that ultimately will become U.S. citizens.

The House immigration bill would use the same restrictive basic criteria as the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. Its authors argue that if the requirements were good enough for President Obama who created DACA in 2012, they should be good enough for Democrats today. But as an act of prosecutorial discretion, DACA was never meant to be permanent immigration law, and in any case, President Obama tried to update its eligibility requirements in 2015, only to be stopped by the courts. The bill wouldn’t stop there. The House plan imposes additional eligibility requirements that would exclude even more Dreamers from receiving permanent protection.

The House bill will exclude Dreamers who entered after June 15, 2007, who entered at any age over 15, or who were over the age of 31 on June 15, 2017 (or 37 today). By the time the bill is implemented, people who had been residing in the United States for 10 or 11 years would be excluded from receiving status under the bill. The bill also requires a high school degree or equivalent or high school enrollment if the applicant is younger than 18. These restrictions were also in DACA, but the new bill would go even further to restrict eligibility. An applicant would be disqualified for having more than a single non-traffic-related misdemeanor, including immigration-related offenses; ever having missed an immigration court appearance; or having ignored an order to leave the country.

The biggest new restriction would be the requirement that Dreamers who are not students, disabled, or primary caregivers demonstrate that they can maintain an income of at least 125 percent of the poverty line. Not only do many Dreamers have incomes beneath this threshold, but also, if they have already lost DACA or never applied, it will be impossible for them to receive a legal job offer or demonstrate legal employment for the purposes of their application. This creates a catch-22 for applicants: prove you can support yourself in order to get work authorization in order to support yourself. (This provision should also concern employers which could see their records become the focus of government attention.)

In addition, receiving status under this bill will be far more expensive than receiving status under DACA. The bill would impose a fine—what the bill refers to as a border security fee—of $1,000. In addition, applicants would need to pay a fee to cover the cost of their application. DACA also had an application fee of $495, but the fee under this new bill would likely be more than double that because it requires an in-person interview and a medical examination. This will make the legalization more like applying for permanent residence, which costs $1,225. All told, applicants would need to pay about $2,225—4.5 times as much as DACA. This comes on top of any attorney fees. Many DACA applicants cite the cost as a primary challenge. MPI’s analysis also points to income as “strongly affecting” Dreamers’ ability to apply.

Finally, the bill would impose a 1-year filing deadline. This means that applicants would have just one year to gather their information, find an attorney, and save $2,225 to apply. For comparison, only 64 percent of DACA applicants submitted applications in the first 13 months of the program. This time limit will needlessly suppress applications.

Why Relatively Few Dreamers Would Even Receive Temporary Relief

In January 2018, the Migration Policy Institute used the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey to estimate that there were 1.3 million Dreamers eligible for DACA. Another 120,000 were too young to apply for DACA, but would be eligible under this legislation so long as they were enrolled in school. However, this eligible population must be reduced based on the new requirements. We estimate conservatively that the income threshold would exclude about 15 percent of the DACA eligible population. This figure is based on the share of Central American immigrants who entered between 1982 and 2007 who are below 125 percent of the poverty line, are not in school, and are not unable to work due to disability or being the primary caregiver, as recorded in the 2017 Current Population Survey.

The misdemeanor requirement is more difficult to place a precise number to, but the government says that 17,079 DACA recipients have at least two arrests, assuming that 75 percent of those arrests ended in conviction. That would reduce 12,809, or 2 percent of the DACA recipient population. Assuming that this rate would apply to the DACA eligible population as a whole (even though it is more likely that that population has more convictions that the DACA population itself), this would reduce the eligible population by another 26,000. Thus, the maximum number of Dreamers initially eligible for status under the House bill is 1.17 million. Even this is likely an overestimate because we cannot estimate how much the noncriminal restrictions (e.g. prior removal orders, false claims of U.S. citizenship, etc.) could further reduce the eligible population.

Even fewer will actually apply. Even after six years of DACA, only 61.4 percent of the eligible population applied for and received DACA. While the promise of a pathway to citizenship could result in a higher participation rate, other elements in this bill will suppress application rates, neutralizing the greater incentives to apply. Furthermore, the initial status is temporary, and the pathway to citizenship is not guaranteed. In fact, unless Congress funds the border wall repeatedly in future years, the path to citizenship would never materialize at all. Moreover, the fact that the cost will be about 450 percent higher will prevent many Dreamers from applying (as noted above).

Many Dreamers failed to apply for DACA because they didn’t realize that they were eligible, believing that they had to have finished high school or that those who had been ordered to leave the country could not sign up. This bill’s new and more complex eligibility requirements will only introduce more confusion. The risk of a denial may keep some from taking the risk to apply. Nearly 8 percent of applicants for DACA were rejected.

The uncertainty and distrust associated with the Trump administration’s enforcement actions would only add to the concern about handing over information. As we’ve noted before, many Dreamers expressed concern that their application could be used to target their families. The House bill attempts to address this fear by limiting how their application information can be used, but it amplifies the fear in other areas by providing enforcement resources and new legal authorities to the administration to speed up deportations. A future Congress could change this privacy protection at any time, and at this point, few immigrants may trust the administration to follow this type of technical “firewall.”

According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the last major legalization—the 1986 amnesty—had only a two-thirds participation rate, despite the less strict criteria than the ones contained in BSIF. Ultimately, we conservatively chose to use the CBO’s higher rate of 67 percent, rounding it up to 70 percent—10 percentage points higher than DACA’s initial enrollment rate. Based on this analysis, we can conclude that at most 820,000 Dreamers would receive initial legal status under the House GOP proposal.

Why Relatively Few Dreamers Would Receive Permanent Residence & Citizenship

Under DACA, which had no additional requirements at all to extend status other than maintaining residence in the United States for another two years, just 85 percent of initial enrollees maintained status through the end of the program. Some of this drop-off can be explained by people failing to graduate high school for a variety of reasons, but the additional cost is important as well. Under the House bill, applicants for extension of their temporary status would be required to pay a fee of another $1,225 fee (2.5 times more than DACA) and have stayed in the United States for another 6 years. Assuming this rate remains roughly the same, only 698,620 would likely end up receiving an extension under the House bill.

After receiving the extension, Dreamers—as well as some legal immigrant Dreamers*—would be able to apply for a pathway to permanent residence. The bill creates a complex points system that will prioritize applications from those with more education, longer work histories, or better language skills. But the minimum threshold for points is low enough that anyone who qualified for the initial status would be eligible to apply. Of course, there is not a strong incentive even to apply for this status, and the cost of applying for permanent residence is another $1,225. They would have to apply over the course of a 15-year period, starting five years after the initially received status. We assume that about 90 percent would apply for permanent residence. Thus, only 628,758 Dreamers would likely receive permanent residence—a path to citizenship—under the House proposal.

Finally, only about two thirds of those who receive permanent residence are likely to apply for citizenship. While Dreamers are probably more likely to apply for citizenship than other immigrants, immigrants from Mexico and Central America are much less likely to apply for citizenship than immigrants from other countries—all have naturalization rates below 50 percent—and 89 percent of DACA recipients are from Central America or Mexico. These two facts work in opposite directions, leading us to assume that Dreamers will naturalize at the average rate for all immigrants—67 percent. Based on this assumption, just 421,268 immigrants are likely to become U.S. citizens under the House compromise bill.

Conclusion

In the best case scenario, the House GOP plan would likely provide a pathway to citizenship to fewer than 630,000 Dreamers—barely a third of the president’s promise in January and just 18 percent of the entire Dreamer population. Moreover, only an estimated 421,000 immigrants are likely to become citizens.

If Congress wants to fulfill the president’s promise of a pathway to citizenship for 1.8 million Dreamers, it would need to institute a broader legalization program for Dreamers with as few risks and costs, and as little confusion, as possible. Congress would also need to provide legal certainty in some form for their parents to mitigate fear of coming forward. Members of Congress should also not exaggerate the extent of the legalization of Dreamers as part of a strategy to justify questionable policy choices, including reducing legal immigration and eliminating several immigration categories.

Table 2 compares the eligibility criteria and requirements under the BSIF Act to those under DACA and the Securing America’s Future (SAF) Act, which is the other bill under consideration this week.

Table 2: Comparison of Pathways to Status & Citizenship Under House Bills and DACA

*The legal immigrant Dreamers would slightly increase the eligible population, but there are so few who would meet the requirements (10 years of continuous residency before the bill passes plus 5 or 6 more after it is implemented) that it would not substantially alter these numbers. In any case, the estimates of the Dreamer population from MPI could include people in temporary statuses that have characteristics similar to those without status (inability to access welfare or receive certifications for legal employment).