Before the cuts: a bureaucracy baseline from an employment equity lens

2025/07/19 Leave a comment

As this article is behind the Hill Times paywall, am sharing this analysis on my blog (have added Indigenous hiring, separation and promotion tables):

Working site on citizenship and multiculturalism issues.

2025/07/19 Leave a comment

As this article is behind the Hill Times paywall, am sharing this analysis on my blog (have added Indigenous hiring, separation and promotion tables):

2025/06/17 Leave a comment

Good question:

The federal public service continued to increase the number of women, Indigenous people, visible minorities, and people with disabilities in its ranks between 2023 and 2024, according to the latest report on employment equity. But as the federal public service now begins to shrink for the first time in over 10 years, some have raised concerns that job cuts will hamper progress for equity-seeking groups….

TBS publishes some rich infographics and infographics: Employment Equity Demographic Snapshot 2023–2024

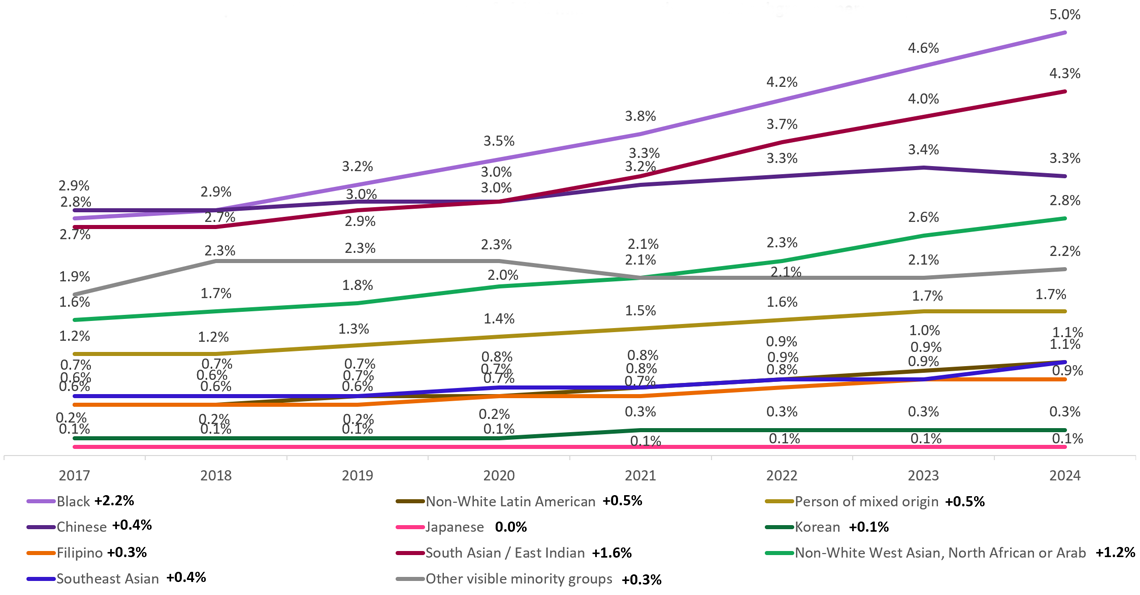

Figure 33: Representation trends for members of visible minorities by subgroup – percentage

2024/07/30 Leave a comment

Of note and very likely (employment equity excerpt):

…Mr. Poilievre said he wanted to live in a country where people pay lower taxes and are burdened by fewer rules, but also where they “have freedom of speech, where they’re judged on their merits, not their ethnicity, gender, sexuality, etc., where parents have ultimate authority over what their kids learn about sexuality and gender, where we go after criminals not after hunters and sport shooters, where we rebuild our military to have strong standing in the world.”

The Liberal agenda of promoting diversity within the public service – gone. Protections for gender-diverse youth – gone. Efforts to combat discrimination in the criminal justice system – gone.

Pretty much every major element of the Liberal environmental, social and justice agenda – gone….

But there is a reason the Conservatives are so far ahead in the polls. Things don’t feel right. Even the most fervent supporter of open immigration (and I am one) is alarmed by the out-of-control flood of people coming into the country. Inflation and high interest rates have lowered the standard of living for millions of people. The regulatory environment has become far too complex. And the Liberals have failed to persuade most of us that they get all this and are working to fix it….

Source: Pierre Poilievre makes his case for dismantling what the Trudeau government has built

2024/06/05 Leave a comment

My latest analysis, focussing on diversity among executives as well as an update on hirings, promotions and separations:

Source (behind firewall): Executive Diversity within the Public Service: An Accelerating Trend

2024/04/18 Leave a comment

Definitely worth a look, for the richness of the data as well the insights into the government’s diversity and inclusion priorities and how it stitches the narrative together with political and Canadian public priorities.

Intro has the key messages:

In Budget 2024, the government is making investments to close the divide between generations. For younger Canadians, the government is taking new action to reduce tax advantages that benefit the wealthy, is investing to build more homes, faster, is strengthening Canada’s social safety net, and is boosting productivity and innovation to grow an economy with better-paying opportunities.

These efforts will improve the lives of all younger Canadians, and their impacts will be greatest for lower-income and marginalized younger Canadians, who will benefit from new pathways to unlock a fair chance at building a good middle class life.

This starts with a focus on housing. Resolving Canada’s housing crisis is critical for every generation and the most vulnerable Canadians. The government is building more community housing to make rent more affordable for lower-income Canadians, including through:

These investments provide Canadians and younger generations with opportunity ––finding an affordable home to buy or rent; having access to recreational spaces, amenities, and schools to raise families.

Having a place to call home creates a broad range of benefits. When survivors of domestic partner violence can find affordable housing, this creates a safe home base for their children to break cycles of violence and poverty. When Indigenous people can find affordable housing that meets their specific needs that means they can access culturalsupports to help heal from the legacy of colonialism. When persons with disabilities are able to find low-barrier or barrier-free housing, this enables them to utilize the entirety of their homes.

To ensure that young people and future generations benefit from continued actions for sustained and equitable prosperity for all, this budget makes key investments to guarantee access to safe and affordable housing, help Canadians have a good quality of life while dealing with rising costs, and provide economic stability through good-paying jobs and opportunities for upskilling.”

Interestingly, no mention of the employment equity task force and its recommendations, although it is mentioned in the Budget.

Immigration aspects are limited to “continued funding for immigration and refugee legal aid” (but the Budget has significant funding for immigration and reflects the government’s pivot away from unlimited temporary workers and international students and post 2015 ending annual increases).

The Budget also has a reference to “Permit the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC) to disclose financial intelligence to provincial and territorial civil forfeiture offices to support efforts to seize property linked to unlawful activity; and, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada to strengthen the integrity of Canada’s citizenship process (with little to no detail).”

No surprise, but the 2019 and 2021 election platform commitments to eliminate citizenship fees remain unmet.

The Government’s proposed reduction in the public service by 5,000 public servants over four years (1,250 per year) is meaningless as the 2022-22 EE report shows annual separations more than 10 times that:

One thought that crossed my mind while browsing this close to 40 page document is whether this level of detail and effort would survive a change in government. Unlikely IMO, given the pressure to reduce spending and the CPC general aversion to excessive employment equity reporting and measures.

Source: Budget 2024, Statement on Gender Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion

2024/03/28 Leave a comment

The latest report, with a range of additional information compared to previous reports: EX1-5 level breakdowns, more longer-term data sets, summary salary distribution, seven-year hiring, promotion and separation datasets, top five/bottom five occupational group etc. Overwhelming amount of data than needed for more general audiences but wonderful for nerds like myself.

In addition, TBS has implemented, on a provisory basis pending the revision to the EE Act, in this report separate equity group for Black public servants, as recommended by the EE Task Force. However, likely reflecting data issues, it has not done so for LGBTQ as also recommended by the Task Force, giving the impression of being a secondary priority and likely reflecting greater advocacy (Black Class Action class action etc).

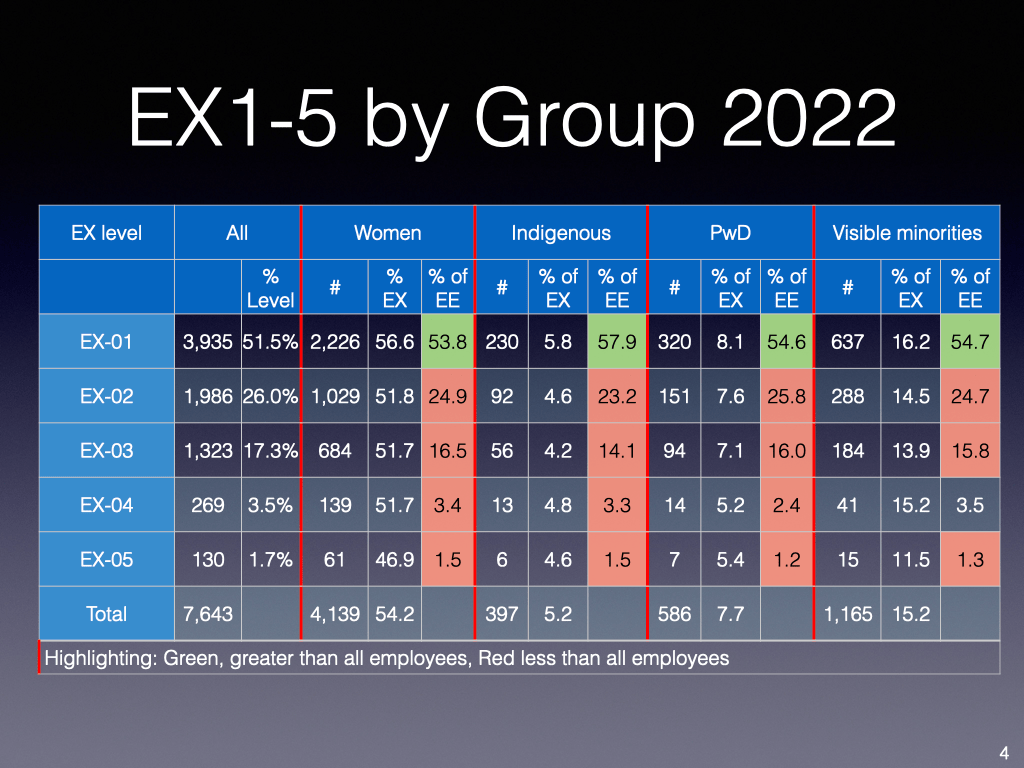

Needless to say, representation by EX level will likely provoke the most interest.

Figure 1 provides the overview numbers, with relatively small variations between the equity groups, with the expected pattern of greater representation at the EX-1 level with the exception of visible minorities at the EX4 level which match the general EX4 population.:

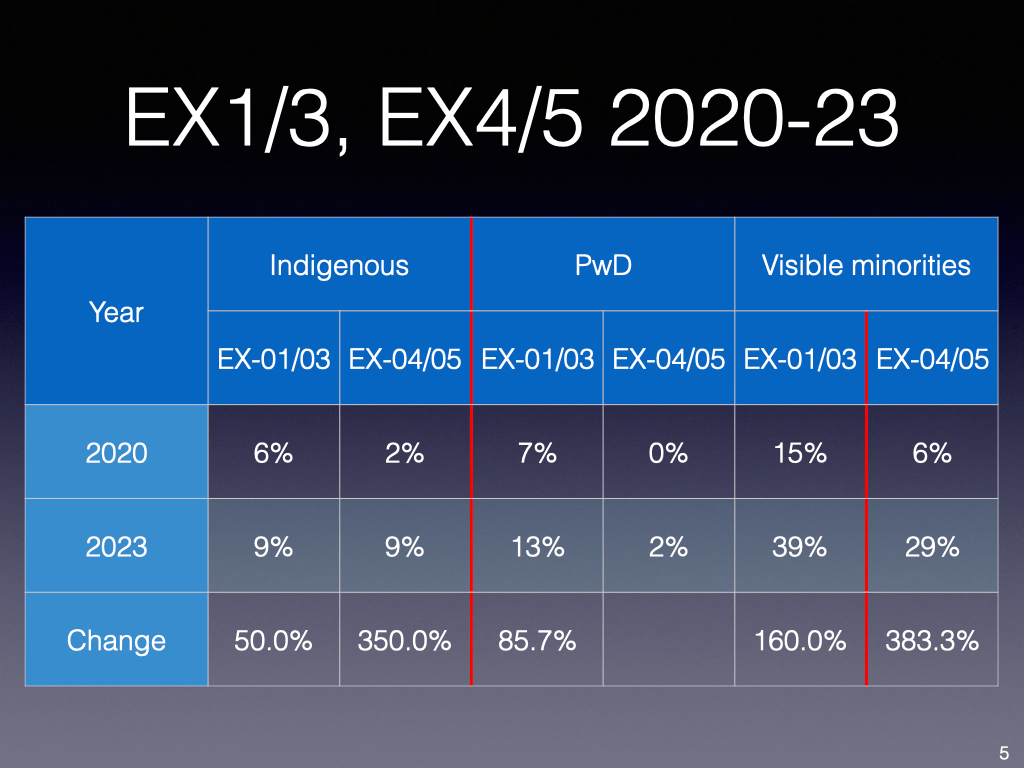

Figure 2 highlights the 2023-2020 comparison between junior and medium level EX (directors and DGs) and senior EX (ADMs), and the percentage increase during this period. The steep increase can likely be interpreted in part to the public service’s overall diversity efforts and the Clerk’s Action call:

Figure 3 compares all employees, all visible minorities, not Black employees, Black employees only and their respective distribution among EX categories, taking advantage of the new section on Black employees. To address the “less than 5” issue, I have collapsed the EX4 and EX5.

Only at the junior EX-01 level, do all three groups exceed the overall distribution. Non-Black visible minorities are more strongly represented than Black employees at all levels save for the EX-01 level, relatively minor but not insignificant.

By including this separate analysis of Black public servants, the report only highlights the limitations of such a carve-out.

My previous analyses of the past 6 years of disaggregated data highlighted the importance of comparisons among all visible minority groups with respect to Black public servants, given than their representation, hiring, promotion and separations are stronger than a number of other groups (How well is the government meeting its diversity targets? An intersectionality analysis). By being selective, this presents the situation of Black public servants as being worse than such comparative data demonstrates. I will be updating this hiring, promotion and separation analysis but do not expect the trend to differ.

On a general level, I was struck by the rapid year-over-year growth of the public service, from 236,133 to 253,411, or 7.3 percent.

Hardly sustainable and should the Conservatives win, as appears likely, the cuts will be deep and painful for the public service. Given that employment equity is unlikely to be a priority for such a government, this may be one of the last extensive and comprehensive reports (they were particularly lean during the Harper years). Should the Liberal government not pass new EE legislation during its mandate, unlikely that a Conservative government would given general ideological aversion, financial pressures and higher priorities.

Source: Employment Equity in the Public Service of Canada for Fiscal Year 2022 to 2023

2024/02/05 Leave a comment

This is quite an impressive website and analytical tool. Unlikely, IMO, to be of use to most job seekers but likely will be of use to stakeholders, governments and industry associations. Will be interesting in a year of so to get some web metrics on its use:

Every Canadian deserves a real and fair chance at success. Reducing pay gaps and improving representation means knocking down the barriers that hold back marginalized communities in the workplace. In order to do this, we need to know where the gaps are.

Today, Minister of Labour, Seamus O’Regan Jr., launched Equi’Vision, a new website that shines light on the barriers to equity experienced by women, Indigenous peoples, persons with disabilities, and members of visible minorities in federally regulated private sector industries. It provides user-friendly, easily comparable data on workforce representation rates and the pay gaps experienced by members of the four designated groups recognized under the Employment Equity Act. With Equi’Vision, Canada becomes the first country in the world to make this level of information publicly available.

Equi’Vision data is submitted by employers with 100 or more employees as part of their annual reporting to the Labour Program under the Employment Equity Act. Individual employee information, including data related to individual salaries, is not reported or disclosed.

Better information leads to better, more informed decision making. By making this information publicly available, the Government aims to draw attention to the persistent issues in Canadian workplaces that are maintaining pay gaps and preventing representation, so that businesses are encouraged to act upon them.

Reducing pay gaps and improving representation requires all partners – businesses, workers and government – joining together to help create safe and inclusive workplaces for all workers, because that’s where workers are at their best. That’s a good thing for our economy, and for all Canadians.

Source: Minister O’Regan launches first of its kind pay transparency website: Equi’Vision

Direct Link to Equi’Vision: https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/corporate/portfolio/labour/programs/employment-equity/pay-gap-reporting.html

CP link: Federal government launches new pay transparency website for four key groups

2024/01/22 Leave a comment

Good overview. One issue I have is the lack of comparison with other minority groups. Citing the numbers for Black public servants without the other groups provides an incomplete picture, as the table below shows, highlighting that other groups have more significant under-representation than Blacks, both at the all public service and EX levels. Disaggregated data for the last six years shows similar differences (https://multiculturalmeanderings.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/ee-analysis-of-disaggregated-data-by-group-and-gender-2022-submission-1.pdf):

Jasminka Kalajdzic, director of the Class Action Clinic at the University of Windsor, says the mere pursuit of the lawsuit has already led to more changes than what a public servant could ever achieve with a grievance.

For example, Treasury Board is working on a more accurate self-identification process and centralizing employment equity data collection and reporting. As well, many departments have created anti-racism secretariats.

The government committed to a Black justice strategy and set aside $46 million in funding for a Black mental-health plan, although efforts to get that up and running have been mired in controversy.

The government recently announced a new panel to develop a “restorative engagement” program to address discrimination.

There has also been a flurry of promotions. In August 2022, Caroline Xavier became the first Black deputy minister when she was appointed president of Communications Security Establishment – 33 years after Ontario appointed its first Black deputy minister.

The Black Executives Network, established in July 2020, delivered its first report in June 2023, which noted “tremendous progress” in building a Black executive community over the past three years. The number of Black executives in the federal public service has grown to 168 today from 68 in 2016, with four deputy ministers and 15 assistant deputy ministers and a few dozen directors-general.

That’s still only about 2.3 per cent of the executives in the core public service, while Black people account for about 4.2 per cent of all public-service employees.

“This (issue) is so much bigger than the Black class action,” says Courtney Betty, the plaintiffs’ lead lawyer. “This is reflection of Canadian society. This is who we are. And for many Black individuals, that’s what they feel. It’s not a reality for any other Canadian. But for Black Canadians, it is a reality.”

Source: Black public servants locked in three-year legal battle with Ottawa with no end in sight

2023/12/14 Leave a comment

Two contrasting takes, starting with predictable support from advocates:

…

A news release by Employment and Social Development Canada said that, on top of creating the two new groups, “initial commitments to modernize the Act” included replacing the term “Aboriginal Peoples” with “Indigenous Peoples,” replacing “members of visible minorities” with “racialized people” and making the definition of “persons with disabilities” more inclusive.

Adelle Blackett, chair of the 12-member Employment Equity Act Review Task Force, said the recommendations were designed to address a lack of resources, consultation and understanding of how legislation should be applied.

Blackett noted that the report offered a framework to help workplaces identify and eradicate barriers to employment equity.

Nicolas Marcus Thompson, executive director of the Black Class Action Secretariat, a group that in 2020 filed a lawsuit against the federal government claiming systemic workplace discrimination against Black Canadians, said the commitment marked a “historic win” for workers.

He added this could not have been done without the work of the Black Class Action.

…….

Jason Bett of the Public Service Pride Network said that group “wholeheartedly” endorsed the report’s recommendation to designate Black people and 2SLGBTQIA+ people as designated groups under the Employment Equity Act.

“Our network has been actively engaged in the consultation process with the Employment Equity Review Task Force, and we are pleased to note our contribution to the report,” Bett said. “The PSPN is committed to collaborating on the effective implementation of the recommendations, contributing to a more inclusive and equitable employment landscape in the federal public service.”

Source: Advocates, union applaud legislative commitment for groups for Black, LGBTQ+ workers

Equally predictably, the National Post’s Jamie Sarkonak has criticized the analysis and recommendations (valid with respect to a separate category for Black public servants given that disaggregated data in both employment equity and public service surveys highlight that 2017-22 hiring, promotion and separation rates are stronger than many other visible minorities groups and indeed, not visible minorities: see ee-analysis-of-disaggregated-data-by-group-and-gender-2022-submission-1):

Why would the task force recommend a special category for Black people when the law already privileges visible minorities? The report writers largely cited history (slavery and segregation), as well as employment data. Drawing attention to hiring stats, it said that when comparing Black people to other visible minorities in the federal government, “representation between the period of job application, through automated screening, through organizational screening, assessment and ultimately appointment fell from 10.3 per cent down to 6.6 per cent.”

This analysis ignored the fact Black people, accounting for only four per cent of the population, apply and are hired at higher rates compared to Chinese (five per cent of the population) and Indian minorities (seven per cent). Because Black people are comparatively overrepresented in hiring, this should satisfy DEI mathematicians. The numbers also don’t explain why failed applicants were screened out: were these applicants simply unqualified?

The report also finds that Black employees from 2005 to 2018 had a negative promotion rate relative to non-Black employees — another non-proof of racism, because it’s possible those employees simply didn’t merit a promotion. Federal departments, noted the report writers, have nevertheless wanted to make up for these discrepancies by focusing their efforts on hiring Black people — but were unable to, because the diversity target law targets the broader “visible minorities” group.

The task force also pointed to Canada’s “distinct history of slavery,” abolished by the comparatively progressive British Empire in 1834 before Confederation, as another reason for special status

Slavery was objectively wrong, but it is much less clear why it should factor into special hiring considerations today. There were relatively few slaves in Canada and not all of them were Black. It would be notoriously difficult to determine who in Canada is still affected by this history — and impossible to hold others living today responsible. Additionally, the majority of Canada’s Black population is made up of immigrants who are unlikely to trace family lines back to enslaved Canadian ancestors.

Source: Jamie Sarkonak: Liberals to mandate reverse discrimination with job quotas for Black, LGBT people

Link to full report: A Transformative Framework to Achieve and Sustain Employment Equity – Report of the Employment Equity Act Review Task Force (on my reading list)

2023/10/25 Leave a comment

The federal government has announced the assembly of a new panel that will support the design and creation of a new “restorative engagement program” to address discrimination, violence and harassment in the federal public service.President of the Treasury Board Anita Anand announced the creation of the panel of experts at a press conference Monday. “We are working to create a safe and inclusive workplace where everyone can be their true self,” Anand said in a statement. “This panel of experts will bring a wealth of knowledge and experience to help shape the new restorative engagement program. Their insights and contributions will be instrumental in shaping recommendations that support truth, healing, and respect.” The panel comprises four recognized experts in clinical psychology, mediation, dispute resolution and restorative justice.They include Jude Mary Cénat, an associate professor at the University of Ottawa’s School of Psychology and chair of the Interdisciplinary Centre for Black Health, and Director of the Vulnerability, Trauma, Resilience & Culture; Linda Crockett, founder of the Canadian Institute of Workplace Bullying Resources and the Canadian Institute of Workplace Harassment and Violence; Gayle Desmeules, founder and CEO of True Dialogue Inc., which provides customized training, facilitation, mediation and consulting services; and Robert Neron, a senior arbitrator and workplace investigator and former adjudicator for the Independent Assessment Process of the Indian Residential School Secretariat. The announcement comes less than a week after a report by the auditor general of Canada, Karen Hogan, criticized federal departments and agencies for not doing enough to measure inequalities and improve the experiences of racialized employees in the workplace.

Analyzing six government departments and agencies between 2018 and 2022, Hogan’s office found that, while many initiatives have been launched to address inequities in the workplace, none have resulted in the “full removal of barriers and in the achievement of equity.” It highlighted that organizations have failed to effectively report on progress, identify barriers faced by staff and, at the manager level, take accountability for behavioural and cultural change.Among the organizations analyzed in the report, a higher percentage of visible minority respondents than non-visible minority respondents indicated that they were a victim of workplace discrimination. However, the surveys showed that racialized respondents were more likely to feel they couldn’t speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal. Joining the conference virtually, Crockett said the panel “cannot not” deal with the issues raised by the report, adding that employees’ fear of retaliation and reprisal is a critically important issue to address. At this stage, however, panelist Neron said it’s “premature” to determine the recommendations that will be made as engagement has not yet taken place.

The restorative engagement program is part of a broader government-wide strategy to identify, address and prevent harassment, discrimination and violence in the workplace, according to a news release shared by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS).“The goal of a restorative engagement program is to identify, through open dialogue, ways to address harm and promote healing for employees who have reported experiencing harassment, discrimination and violence in the workplace,” the release stated. “By placing individuals at the centre of the process and focusing on understanding the connections, root causes, circumstances, and impacts related to harm, the restorative engagement program will help drive cultural and systemic change within the public service.” TBS said similar programs are being used “increasingly” across Canada, including by the Canadian Armed Forces and the Department of National Defence.

Anand said the announcement of the program is not just an exercise in public relations. As a racialized person herself, she said it’s crucial the government continue to address discrimination in the public service.

While she is not a member of the panel, Anand said she believes the work happening across the government to develop programs supporting the better treatment of minorities and women who have been subject to sexual harassment can serve as valuable examples for the team.Participating online, Desmeules said Monday that an interdepartmental advisory working group had been established to support the program’s engagement process, made up of public servants from departments and locations across Canada who have experience in diversity, inclusion, harassment, discrimination, conflict management, labor relations, disability management and restorative justice, with the Canadian Armed Forces “sitting at that table.” “We’re just capturing collective wisdom here,” Desmeules said.

In its 2023 budget, the federal government committed $6.9 million over two years to TBS to advance a restorative engagement program to “empower employees who have suffered harassment and discrimination, and to drive cultural change in the public service.” It said the program would allow employees to have a safe, confidential space to share experiences of harassment, discrimination and violence.

“According to the 2020 Public Service Employee Survey, certain federal public servants are more likely to experience harassment, racism, and discrimination in the workplace,” the budget stated. Those public servants include those identifying as Black, racialized, women, Indigenous, persons with disabilities or 2SLGBTQI+.

The budget outlined that $1.7 million would be sourced from existing departmental resources, with funding to also support a review of “the processes for addressing current and historical complaints of harassment, violence and discrimination.”

TBS said the panel’s work will come with a price tag of about $550,000.

The panel is expected to write a public report on its findings in early 2024, with recommendations on the design of the program to be submitted to the government in the spring.

Source: Feds announce new panel to help address discrimination in the public service