Early indications for Syrian refugees. Given timing of Census (about a year after arrival), too early to draw definite conclusions. However the longer term analysis of refugee economic outcomes, broken down by private sponsorship and government selected, along with country of birth, are more interesting and informative:

The life of a refugee can be many things—dangerous, wearying, heart-rending, boring, nerve-racking, expensive and full of countless unexpected challenges to overcome. It also appears to be quite noisy.

Right now, for instance, the Kitchener, Ont., apartment of Jehad and Baraa Badr is cacophonous—much of it baby noise. Their older son, Hussam, has dropped by with grandson Zain for a playdate with a neighbour’s young child, who is also visiting. Younger son, Adam, makes his own contribution to the din. As do various electronic devices: some reminders for prayer time, others bringing texts and phone calls from friends and family. Rising above all this clamour, however, is Jehad’s exuberant account of the wonders of life in Canada, his gratitude for the help his family has received so far and his many plans for the future.

“I love being here. I love my friends. I love Canada,” he says loudly and with enthusiasm, his expressive body language making up for obvious struggles with language. “Good equality in Canada. Good government. No Syria government. No help.”

After spending three years in Egypt and Turkey—having left war-torn Syria behind in 2012—Jehad, Baraa and nine-year-old Adam arrived in southwestern Ontario in spring 2016 as part of the massive wave of Syrian refugees admitted into Canada following the last federal election. Hussam and his young family arrived a month later. Two other sons, however, will never arrive. Frustrated by the long wait in Egypt, they paid smugglers to take them across the Mediterranean Sea to Italy and then made their way to Austria, where they now live permanently.

This separation of their family is just one of the many tests the Badrs have had to endure since fleeing their homeland. As with the rest of the more than 50,000 Syrian refugees who have arrived in Canada since 2015, settling into Canadian society requires grappling with the many cultural nuances and obligations of their new home. But most significantly, it means mastering a new language and finding employment. “I need a job,” says Jehad, 59, in his halting, declarative style. “I need English. But job and school? Problem.” It is a problem with both personal and political implications.

If there was a single defining issue of the 2015 federal election, it was debate over the proper national response to the Syrian refugee crisis—a question seared into our collective consciousness by that heart-wrenching photo of young Syrian refugee Alan Kurdi’s lifeless body being carried away on a Turkish beach.

Demands for a political response to the humanitarian emergency immediately changed the course of the federal campaign. Prime Minister Stephen Harper said his government would take a total of 10,000 additional Syrian refugees—arguing that to accept any more would create security risks—while maintaining Canada’s military presence in the Middle East as a check on further crises. Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau upped this to 25,000 refugees by the end of the year, and vowed to withdraw our squadron of CF-18s. NDP Leader Thomas Mulcair topped both of his competitors by saying he’d accept 46,000 over several years, as well as end Canada’s military contribution.

In the end, Canadian voters apparently found Trudeau’s offer of 25,000 refugees the most persuasive. And while he failed to make good on his initial deadline, the Prime Minister’s goal was realized by mid-2016. Since then, the flow has slowed but is nowhere near stopping. The most recent count of Syrian refugees admitted into Canada since the election stands at 58,650, exceeding even Mulcair’s highest bid. For this effort, Canada has earned many admirers. “Thank God for Canada!” read a headline in the New York Times this year, lamenting the fact America under President Donald Trump had accepted only 12,000 Syrian refugees.

But taking in large numbers of refugees to widespread international acclaim is one thing. Integrating them successfully for their own happiness and well-being, and to prevent any urgent political or social issue, is quite another. With nativist sentiment rising around the world, and with the emergence of irregular refugees as a new hot-button political issue in the upcoming federal election, it seems both appropriate and necessary to check on the progress of the class of 2015/16. So how are Canada’s Syrian refugees doing?

Statistics Canada recently took a close look at that first cohort of 25,000 Syrian refugees who landed as of May 10, 2016. Employment is the most important metric by which to gauge the integration of refugees into Canadian society. And here the news seems rather disappointing. Only 24 per cent of adult male Syrian refugees were working, according to census data. For government-sponsored male refugees (as opposed to those sponsored by charities, churches or other private organizations), the employment rate was a mere five per cent. These figures are substantially below the 39 per cent average for male refugees from other countries. The gap between female Syrian refugees and those from other countries is equally significant: eight per cent versus 17 per cent.

Such low rates of employment are largely explained by the demographics and timing of the Syrian refugee cohort. In response to the humanitarian crisis, Canada adjusted its acceptance criteria to include more young families with children and fewer working-age males. Standards for language skills and education were also lowered. More than half the Syrian refugees could not speak an official language, compared to just 28 per cent of refugees from other countries. Among adults, less than half had even a high school diploma. (Neither Jehad nor Baraa Badr are high school graduates.)

For Bessma Momani, professor at the Balsillie School of International Affairs and senior fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation, the relatively poor performance of the Syrian refugees in finding work is entirely understandable given their profile. “Canada did a good job of targeting the most vulnerable people,” she says. “This group includes semi-skilled and mostly uneducated people. Some were also injured.” It makes sense that a group chosen for humanitarian reasons would take longer to find their footing in a new country than migrants selected for their employability, she says. Plus, it’s still early days. Many of the Syrian refugees had been in Canada for only a few weeks or months when the census was taken. It would be a supreme accomplishment for anyone to have found a job and learned a new language in such a short time.

As for political fears raised during the 2015 election about security risks and the national capacity to absorb such a large influx of refugees, Momani notes time has proven such claims misplaced. “Canada is a big country with a lot of capacity,” she says. “The debate between 10,000 and 25,000 was really just an arbitrary distinction since we have now taken in over 50,000.” And she highlights how popular providing aid to Syrian refugees proved to be among voters. “I think that surprised many Canadian politicians,” she adds.

Syria’s diaspora may no longer be the dominant political topic in Canada, but refugees remain a key election issue—except that now it’s marked by a growing note of skepticism. After years of pressure from federal Conservatives over the influx of more than 40,000 irregular refugees through unauthorized border crossings, mostly in Quebec, the Trudeau government is now adopting a much tougher stance toward these asylum seekers. The 2019 federal budget, for example, proposes to take away their right to a full refugee hearing; it also boosts funding for border measures to “detect and intercept individuals who cross Canadian borders irregularly.” These irregular border-crossers are mostly from Africa and the Caribbean, not the Middle East.

In another recent development signifying a change in mood toward refugees, the 2019 Ontario budget eliminates all legal aid funding for refugee and immigration programs.

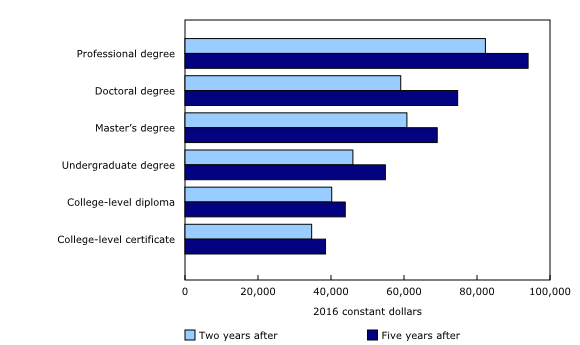

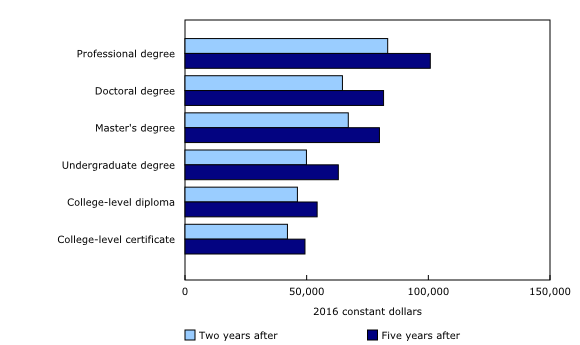

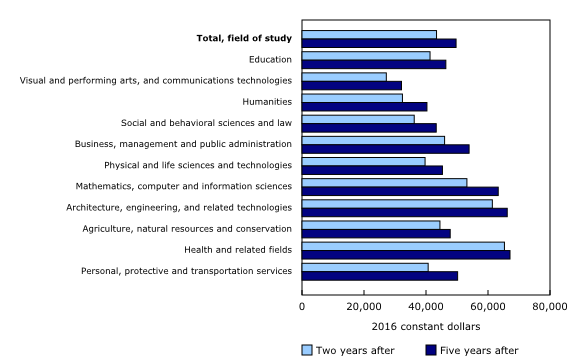

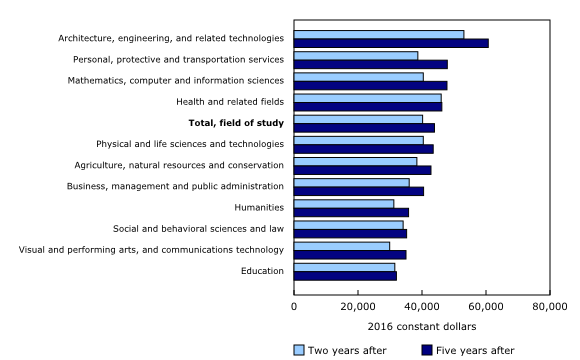

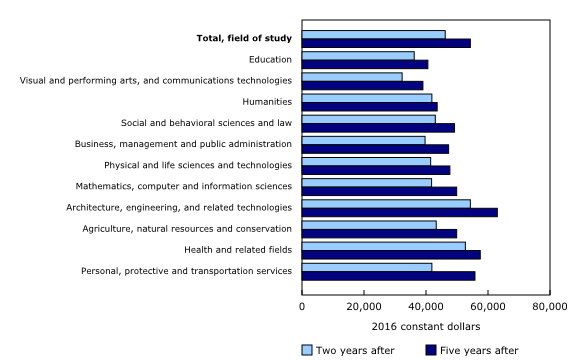

As for the long-term consequences of Canada’s mostly generous approach to refugees, another recent StatsCan study looked at all 830,000 refugees who entered Canada between 1980 and 2009 and found their employment and earnings tend to improve slowly over time, but with some significant variations. Refugees who were privately sponsored seem to do better than those sponsored by the federal government, but this difference evaporates after about a decade.

One puzzle that appears permanent, however, is the role played by culture in the integration process. After 15 years in Canada, StatsCan notes that refugees from certain countries (Yugoslavia, Poland, Colombia, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos and El Salvador) had earnings largely indistinguishable from immigrants accepted on strict economic criteria. But refugees from some other countries (Iraq, Somalia, Afghanistan, Pakistan and China) appear to do noticeably worse, even after accounting for factors such as education, language skills and age. StatsCan admits it has no real answer as to why such differences persist.

It is perhaps too soon to tell which category the Syrian refugees will fall into, but the early figures show those who arrived in late 2015 are already more likely to have a job than those who came a few months later, suggesting a fairly rapid process of integration. “I think we’ll see a lot of new small businesses coming out of this group of Syrian refugees,” says Momani, noting anecdotally that the national shawarma shop sector appears to be undergoing substantial growth. “I suspect by the next census, the numbers [of employed Syrian refugees] will have greatly improved. There is a lot of early success out there.”

Of course the biggest barrier to early success in the job market remains language. And this often requires some difficult choices for newcomers to Canada.

Shortly after arriving in southwestern Ontario, Jehad [Badr] enrolled in an English language school located in the basement of Waterloo’s First United Church, which supported his family’s refugee claim. “First six months, I go to English school. But I need job. I have rent. You need money,” says Jehad, who owned an auto upholstery repair shop back in Syria.

Mounting bills and a gnawing desire for independence eventually convinced him to drop out in favour of a job at a local patio furniture manufacturer. “I wish I go back to school. Maybe when I am old man,” he laughs. Sometimes Jehad answers questions twice, first in Arabic to his son Hussam, who acts as a language coach, and then again in English.

In contrast, Baraa, 49, has stuck with her language training and is now close to graduating. “When I am done, maybe I study more or look for a job,” she says.

Having chosen work over study, Jehad has already weathered two layoffs in the past two years as a result of the seasonal nature of the patio furniture business. A monthly $3,000 stipend from the church has long since run out and now rent consumes more than half his income. But he remains determined to pay his own way. Responsible for reimbursing the federal government for the cost of his family’s flight from Turkey, Jehad declined the option to pay it back at the modest rate of $9 per month.

“The government got $200 every month. Finished. No debt,” he states proudly, wiping his hands together. To supplement his income, he has also been doing small upholstery jobs on the side. And to save on expenses, he has discovered the wonders of Kijiji. “Six chairs and table. Twenty-five dollar!” he exclaims in disbelief, pointing across his small but homey apartment to his family’s “new” dining room set.

Independent, proud, hard-working and frugal. In many ways, Jehad already seems plenty Canadian. Perhaps the fact the enormous influx of Syrian refugees no longer constitutes a federal election issue can be partly ascribed to Jehad’s impressive work ethic and gregarious nature. As well as his family’s determination to fit into Canadian society. (They will be applying for citizenship shortly.) He even claims to love winter.

“In Syria, when winter comes one day, we drive 50 kilometre to see ice and snow. Everyone excited. Here… ” Jehad tails off, searching for the words to explain how Canadians don’t seem to get quite as excited about the cold stuff. But you get the sense he’ll eventually figure it out. A new home always takes some getting used to.