UK: Say one thing, do another? The government’s record rise in net migration

2024/03/26 Leave a comment

Highlights the difficulties and how parties get captured by their political promises, and then later pay the political price:

Think back to the 2019 election campaign. Quite reasonably, you may not remember every detail of the Conservatives’ manifesto – but perhaps you do recall one promise: to reduce immigration.

Think back further, to 2016 and the Brexit referendum. Then there was a promise to “take back control” of the UK immigration system. And since it left the EU in 2020, the UK does have more control.

But the numbers of people who’ve moved here didn’t go down, they went up.

Since the Brexit vote and the Conservatives’ victory in 2019, the 12 months to June 2022 saw the fastest population growth since the 1960s. Current projections from the Office for National Statistics put the UK on course for 74 million people by 2036 – six million more than there are today.

You’d be well within your rights to ask how that could be? The answer, according to the ONS, is largely immigration.

And one aspect of immigration has received huge amounts of attention from the government and the media. Statement after statement, story after story, has focused on migrants crossing the Channel in small boats – and the government’s efforts to stop them.

Indeed you’d be forgiven for thinking small boats are a major part of why immigration is up. But they aren’t.

No doubt, small boats are an important issue – on a human and national level. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has made “stopping the boats” one of his five priorities.

His government’s flagship Rwanda plan aims to send some asylum seekers who arrive on small boats there – and Mr Sunak is still trying to get the bill through parliament.

But it’s not small boats that are driving an increase in immigration – it’s choices made by the government.

Almost 30,000 people arrived in the UK on small boats last year – something the prime minister has vowed to crack down on There are a number of ways to measure immigration.

Let’s start with one: net migration. That’s the difference between the number of people arriving and leaving the UK each year.

In 2022, it’s estimated to have reached an all-time record of 745,000.

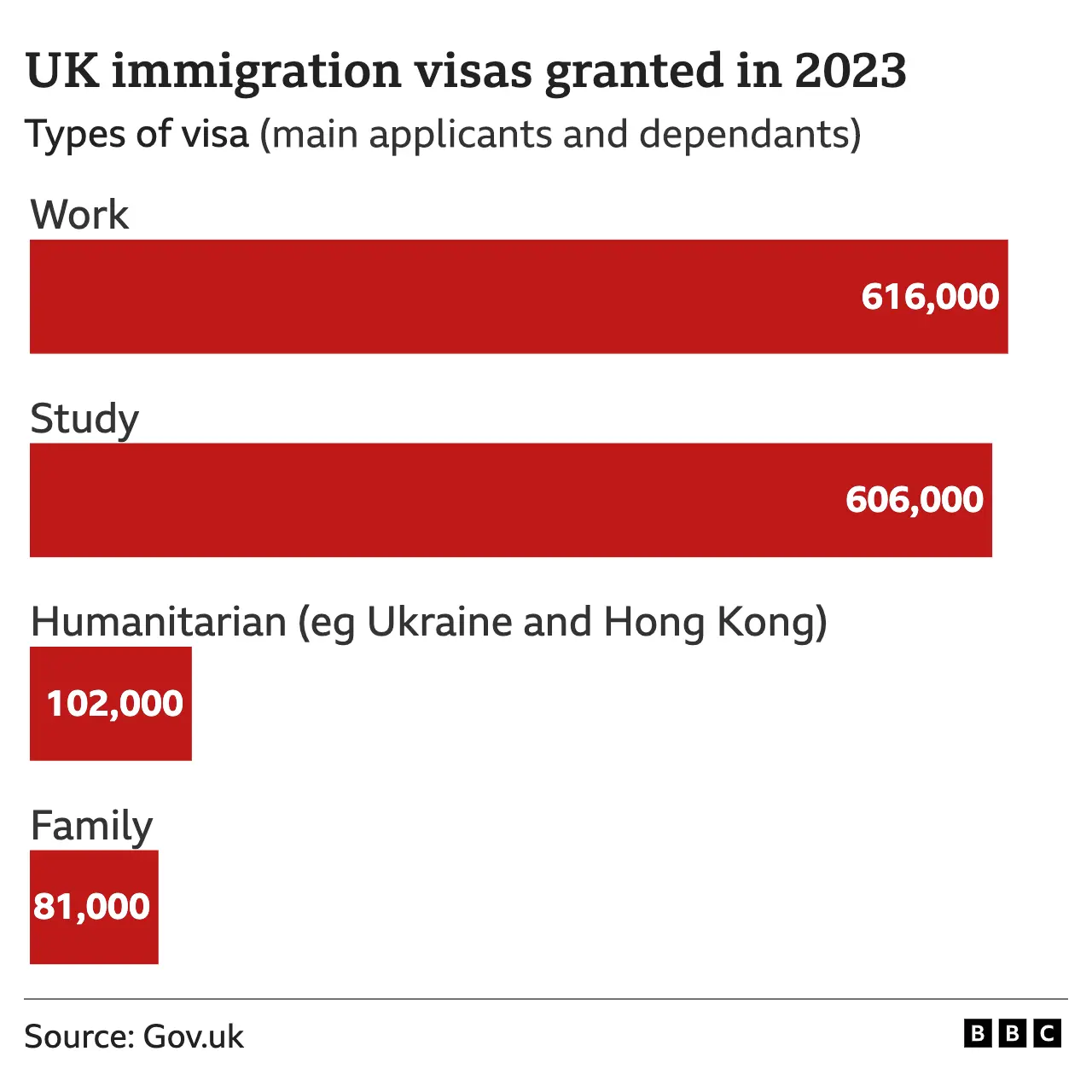

Then, there’s the number of visas issued to people relocating to the UK. Last year there were more than 1.4 million.

For context, last year almost 30,000 people arrived by small boat.

After the UK left the European Union, the government launched a new visa scheme for most people who don’t have a UK passport.

The government decides the criteria for the different visas it issues – these can be for studying, for working, for humanitarian reasons – and other purposes too.

In the words of Prof Brian Bell, who chairs the government’s independent Migration Advisory Committee, the rise in immigration is “the inevitable consequence of government policy”.

We can see how this is the case by breaking down that 1.4 million figure.

In 2022, the government issued almost 300,000 humanitarian visas. But last year the number was 102,000 – that’s just 7% of the 1.4 million visas issued.

The government has been consistent in its response when asked about the record levels of net migration.

Tom Pursglove MP, the Legal Migration Minister, told me: “We’ve seen incredible generosity in our country to people from Ukraine, people from Afghanistan, people from Syria, and other conflict zones. That is an important part of why we’ve seen the figures as they are.”

It is important, no doubt. And there was political consensus that issuing visas to people from Hong Kong, Ukraine and elsewhere was the right thing to do.

But the numbers show that this isn’t the full story.

The government has made other choices that have pushed up immigration.

Brexit and the pandemic added to existing recruitment problems in the social care sector. Care home owners responded by asking the government to make it easier to employ overseas care workers.

Those calls were echoed by the Migration Advisory Committee, which also suggested the government should fund higher wages to attract more British workers into the sector.

The Westminster government agreed more visas could be issued but did not raise wages.

A number of consequences followed.

For care home owners like Raj Sehgal, the changes helped. He filled almost all vacancies in his five Norfolk care homes, with 40% of staff coming from abroad.

“If we didn’t have international recruitment, I think we would probably be closed by now,” he told me.

More overseas staff arrived to work across the sector. But more may be needed. Last year, there were around 150,000 vacancies in England, and recruiting British workers remains difficult.

Let’s look at that 1.4 million figure again. Of all of those visas, more than 146,000 went to health and social care workers, another 203,000 went to their dependants.

This month, the government stopped overseas care workers from bringing dependants, describing the numbers as “disproportionate”. Mr Sehgal says this has already reduced the number of applications he is receiving.

This seems certain to reduce net migration numbers, but it’s not certain how the care sector will find the staff it needs.

If the government’s decisions on social care have driven up immigration, then so have its decisions on overseas students.

First of all, let’s consider the context here.

Tuition fees for domestic undergraduates at English universities are capped at £9,250 a year. That hasn’t risen for seven years – but during the same period, costs have. That has left universities facing financial challenges.

Some of them, like Coventry University, have targeted higher-paying overseas students to help cross-subsidise UK undergraduates. Forty per cent of the students at its campuses across the UK are from overseas.

If domestic tuition fees were raised, it could reduce the need for overseas students. But that would cost a lot. And it hasn’t happened.

Prof Brian Bell argues “that’s a choice of the government not to fund education in a particular way. The inevitable consequence is more immigration.”

The government couldn’t have been clearer about its ambition to attract more overseas students.

In 2019, it even set a target to increase the UK’s overseas student population to 600,000 – by 2030. It achieved that goal nine years early.

On top of that, in 2021, the government reintroduced a post-study work visa which allows overseas postgraduate students to work for two years after their courses finish – or three years if studying for a PhD.

It took the decision despite the Migration Advisory Committee suggesting that it shouldn’t.

All of this did what it was designed to do – attract lots more students. Last year the government issued almost 458,000 sponsored study visas. And almost 144,000 for dependants of postgraduate students.

Together, they made up almost 42% of the more than 1.4 million visas issued last year.

Again, the government was choosing immigration.

Now at this point, we should emphasise that while the government was putting in place policies that promoted immigration, knowing their precise impact was hard.

Dr Madeleine Sumption leads the Oxford Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford. She also sits on the Migration Advisory Committee that advises the government.

Predicting immigration numbers is “incredibly difficult”, Dr Sumption says. “Sometimes it’s much larger than the government expects.”

As the consequences of the government’s own policies became clear, it slammed on the brakes.

In May last year it announced that, from January 2024, most overseas postgraduate students would no longer be able to bring dependants.

This March, the government took further action – it ordered a review of the visa that allows overseas students to stay on and work. This, let’s remember, is the scheme the government had introduced only three years ago.

Legal Migration Minister Tom Pursglove explains: “The government took a view that we thought that that was the right thing to do to support the university sector. But when you consider the dependant numbers that have come with students, that has been very, very challenging.”

The government’s measures appear to be making a difference already. According to Universities UK, some universities are seeing a sharp drop in applications from overseas students for postgraduate courses.

But there’s a risk that as applications go down, so does the income of some universities.

A British Future poll suggests 69% of respondents are dissatisfied with the government on immigration All of these government decisions have contributed to the record rise in net migration, and along with the rise we’re also seeing a shift in public opinion.

The think tank British Future, which tracks UK attitudes to immigration and describes itself as non-partisan, has shared its latest opinion poll with Panorama.

For the first time in four years, the poll suggests a majority of 3,000 respondents – 52% – want overall immigration to fall.

On top of that, 69% of those polled say they are dissatisfied with the government on immigration – that’s the highest since its polling began in 2015.

And this is where we come back to where we started – to the government’s emphasis on the issue of small boats.

The opinion poll also suggests that a little over half of those who say they are dissatisfied with the government’s handling of immigration pointed to small boats – and those concerns are coinciding with concerns about overall immigration.

Dr Sumption told me the media’s focus on small boats has probably created the impression that almost all migration comes that way, “which obviously it doesn’t”.

To reiterate – almost 30,000 people came by small boats last year and 1.4 million visas were issued by the government for people to come to the UK legally.

Some argue that the government has overemphasised the issue of small boats.

When I put that to Tom Pursglove, he countered that the government has a “moral imperative” to “grip that issue”. But he said that shouldn’t stop them, “delivering on the mission around legal migration, which is to get a better balance to bring those numbers down”.

At the moment, by the prime minister’s admission, that balance is off. In November, Rishi Sunak acknowledged, “immigration is too high and needs to come down”.

But his former Home Secretary Suella Braverman made a series of striking claims when I talked to her about Mr Sunak’s approach.

“I think the prime minister has not necessarily assumed that it’s an important issue for the British people,” Ms Braverman says.

“‘I struggled myself as home secretary, even to have a meaningful conversation with him about it. I was left to written correspondence on several occasions throughout a period of 12 months, putting forward policy proposals. But he refused to talk to me.”

I was taken aback by this. I know there is little political love lost since Mr Sunak sacked Ms Braverman last year – but this is the home secretary during the time of one of the sharpest rises in net migration in the UK’s history – claiming the prime minister wouldn’t talk to her about it – at all – for a year.

I double-checked I had heard right. I had.

“We talked about the boats every week, twice a week. We talked to each other a lot about policing and security. On legal migration, I was unable to get a hearing with the prime minister for 12 months.”

Given the importance of this issue to so many people, it is an extraordinary claim.

When we asked No 10 about this, it did not comment.

At the end of last year, the government announced plans to cut net migration by reducing the number of people coming to the UK by 300,000.

Remember, the latest estimate for net migration is 672,000 for the year to June 2023.

The estimate published just before the Brexit referendum – and which, at the time, Boris Johnson called “scandalous” – was 333,000. That estimate has now been revised down to 303,000.

So if the government meets its new target, that would take the numbers back towards where they were… just before the Brexit vote.

The government emphasises that Brexit has given the UK greater control and flexibility to adapt immigration policy to circumstance Some observers watching the government’s statements and actions on immigration are gently raising their eyebrows.

Prof Anand Menon, who leads the independent think-tank UK in a Changing Europe, told us: “I think there is an element of dishonesty in the government at one and the same time implementing these policies and bemoaning them. Or bemoaning their impact.”

There seems little doubt the government’s latest measures will make a difference. Net migration is expected to fall. But if it does, the longer-term challenges that immigration has been easing may come into sharper focus.

Paul Johnson of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, which says it operates on a “non-political basis”, has an uncompromising message on this.

“If you want universities to have as much money as they have at the moment without these foreign students, you need to find some money from British students or the British taxpayer. If you want care homes to be staffed without bringing people in from elsewhere, you’re going to have to pay more. You have to make choices here.”

I’d hoped to ask Labour some questions about how it would approach these choices, but it declined.

This month, the Shadow Home Secretary Yvette Cooper said, “We are very clear that net migration needs to come down” and that a practical plan to tackle skills shortages in the UK is needed.

But are politicians of all parties being straight with us about what these choices involve?

For this government, for any government, these choices will involve difficult and sometimes expensive trade-offs.

Legal Migration Minister Tom Pursglove argues “issues have arisen” and it has “responded to those issues”. It emphasises that Brexit has given the UK greater control and flexibility to adapt immigration policy to circumstance.

Others point to recent data showing that one in five working-age adults are off work in the long-term, with record numbers recorded with long-term sickness.

In the Spring Budget, the Chancellor Jeremy Hunt said it would be easy to fill the 900,000 job vacancies with higher migration, but with 10 million adults not in work, it would be “economically and morally wrong”.

It’s inescapable though, that while the UK now has more control of its immigration system, the government has used that control to allow more people to come to the UK.

To come back to the question I posed earlier: how did that happen?

We can answer that by listing the government’s decisions and by acknowledging that there are powerful long-term factors that appear to encourage higher immigration. Our population is ageing, our birth rate is falling and our economy is struggling to grow.

The government though still insists the numbers will and must come down.

However, despite all the promises, this government chose more immigration. It is unlikely to be the last to do so.

Source: Say one thing, do another? The government’s record rise in net migration