CANADIANS ABROAD: Overview of Recent Research and Implications for Public Policy

2024/04/29 Leave a comment

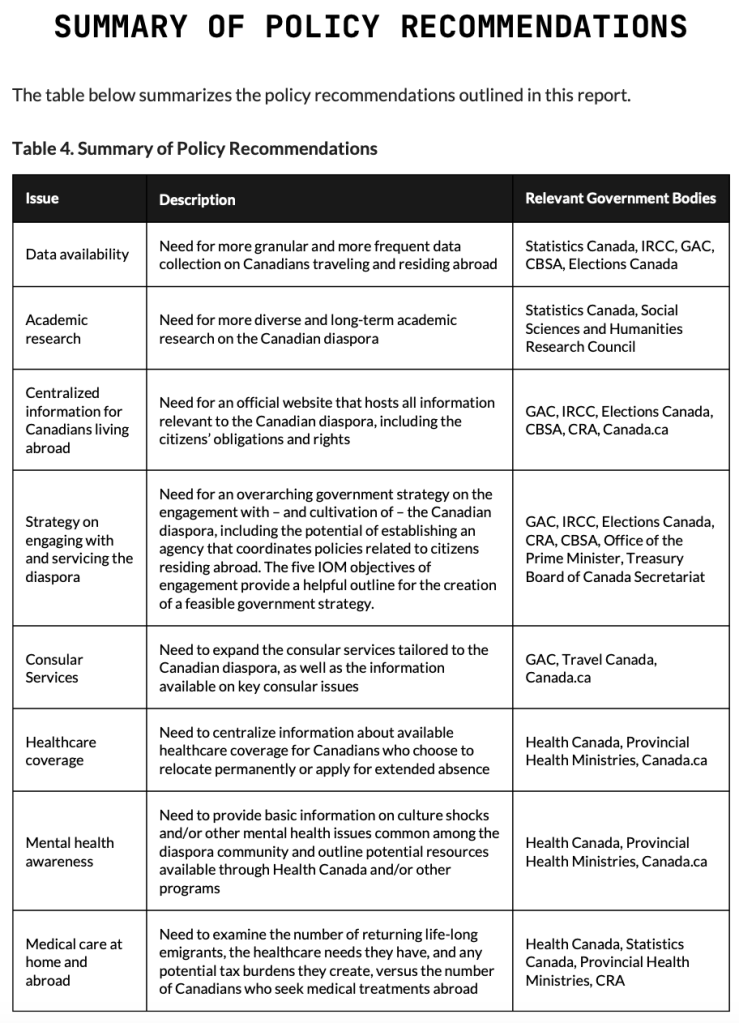

This report, commissioned by Senator Woo, essentially argues for more services and support for Canadian expatriates. While it contains some useful comparisons of provincial health care coverage and non-coverage, as well as provincial election regulations, it is disappointingly light on measures of connection to Canada, whether passport issued to Canadians abroad (no recent public stats apparently) or non-resident taxation (less than 32,000 in 2021).

In terms of the specific recommendations below, my thoughts are as follows:

- Always good to have better and more comprehensive data, along with academic research. For the latter, important to have range of perspectives, from this stating the case for more services (as the report does) to more critical voices.

- On the various recommendations for centralized information for “all information relevant to the Canadian diaspora,” this understates the complexity of compiling and maintaining such a data that incorporates federal and provincial information. The argument for the need appears more theoretical than based upon public opinion research.

- As to the needs for a strategy, hard to argue against that but the challenge, as we seen in so many areas, strategies without serious implementation are more photo ops and virtue signalling than meaningful.

- With respect to consular service, one needs to start at first principles in terms of the obligations and limits to consular service to manage expectations and costs. In general, Canada has been generous in recent crises in terms of family members and permanent residents, even in cases of long-term expatriates with minimal to no current connection to Canada

- More nutty are the arguments regarding healthcare coverage, mental health awareness, and the medical care at home and abroad sections, especially given the strains our healthcare system in Canada is facing. Expats planning to return to Canada are responsible for reinstating coverage and the various provincial websites are easy to find and understand. Is it really a Canadian government responsibility to help expats deal with mental health issues among diaspora communities? There is some merit in studying the impact of the return of expats to Canada on healthcare given that they have for the most part not paid Canadian and provincial taxes but the issue of Canadians seeking medical services abroad is a completely separate issue as these are paid by individuals, not taxpayers.

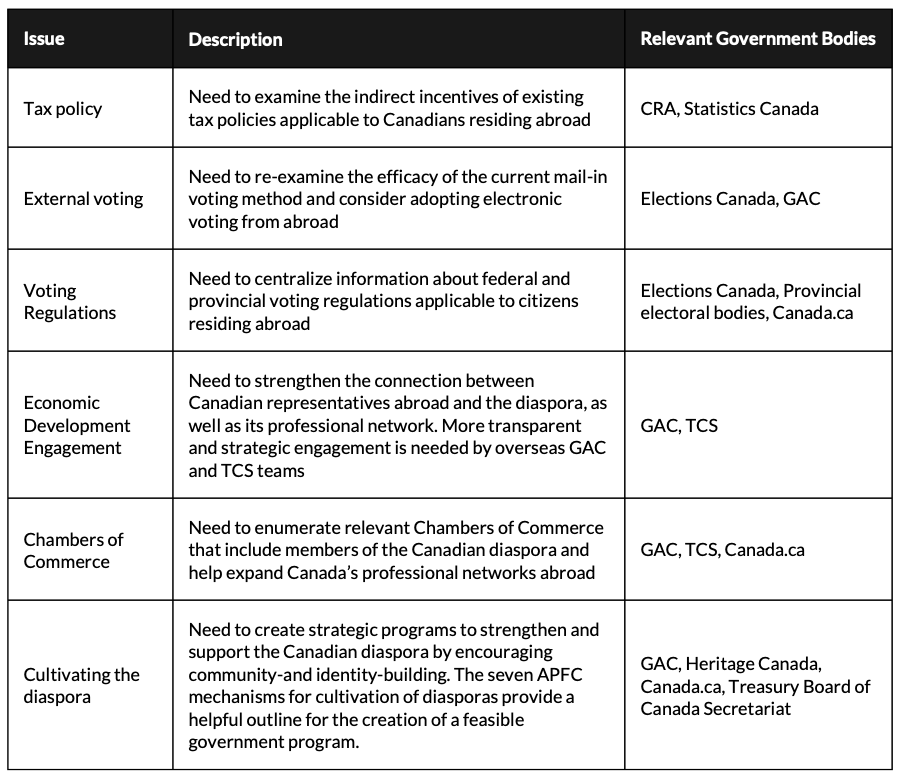

- On tax policy, unclear what exactly is the issue and what are they trying to advocate. Canadian taxation is based on residence and most expats don’t pay Canadian non-resident taxes although some who maintain property in Canada do pay property tax.

- Expat voting is a classic case where the policy arguments are divorced from reality. The report makes the specious comparison between overall voting rates between Canadian and non-residents but not the more telling on that only 55,000 non-resident voters registered, a drop in the bucket compared to the overall number of around three million adult expats. The same concerns regarding the cost of maintaining an updating a database on federal and provincial voting regulations apply. And suggesting electronic voting from abroad when we do not have it in Canada, not to mention the potential cost and security risks, even more hard to justify.

- The last three recommendations – economic development engagement, chambers of commerce, and cultivating the diaspora – already happen to some extent in every embassy that I had worked in. No doubt, could be improved and strengthened.

Overall, the author has an overly optimistic take on the interest and willingness of long-term Canadian expatriates to advance Canadian interests. The vast majority are living their lives in their country of residence, contributing to that country’s economy and society, with relatively few highly engaged in advancing Canadian interests. Those are largely known to embassies and consulates and Canadian interest groups. Again, more could be done but given limited resources and little hard evidence to demonstrate effectiveness, the case is weak.

Source: CANADIANS ABROAD: Overview of Recent Research and Implications for Public Policy