Parties must work between elections to improve diversity, say MPs, candidates

2019/10/30 Leave a comment

The 43rd Parliament will include 51 visible minority MPs, up from 47 after the 2015 election, while the number of Indigenous MPs will remain the same, at 10 out of 338, despite a record number running.

Parties have moved in the right direction when it comes to recruiting and selecting diverse political candidates, but more has to be done between elections to make federal politics accessible, say recent candidates and newly elected MPs.

“It’s not going to cut it,” if parties only focus on bringing in politicians that better reflect Canada’s makeup during pre-election candidate searches, said Liberal MP-elect Han Dong for Don Valley North, Ont.

“Between elections, all parties have to make a deliberate effort to reach out to communities to get them involved in policy discussions,” as a starting point, said Mr. Dong, a former Ontario MPP. “It is so important to generate that interest, to give a sense of involvement in decision-making. That’s how you’re going to get more people step forward and going for public office.”

For Andrea Clarke, who ran unsuccessfully as the NDP’s candidate in Outremont, Que., this year, the question of class and income disparity also makes running for Parliament less accessible to some, often racialized, Canadians.

How to make sure electoral politics are accessible and representative of the population isn’t something that should be discussed for just a few months each campaign season, she said.

“It’s something we need to intentionally build into how we hold our elections, and unfortunately folks who are the farthest have to fight the hardest to make the case that this is what we should be doing,” she said, adding that a lack of representative politics means losing out on having “different voices at the table, advocating for their communities, and their lived experience.”

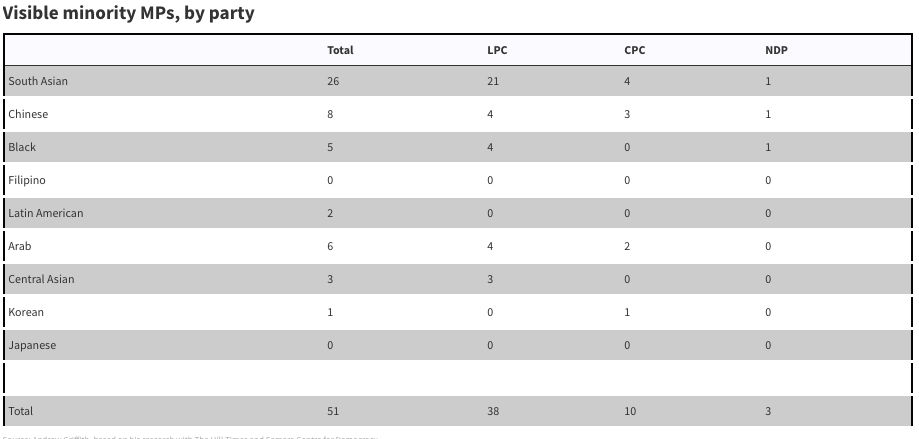

Source: Andrew Griffith, from dataset created by The Hill Times, The Samara Centre for Democracy, and research partners.

The next Parliament will see a slight increase in visible minority representation in the House, with 51 MPs compared to 47 in 2017. The 43rd Parliament has 26 South Asian MPs, eight Chinese, five Black, six Arab, three West Asian, two Latin American, and one Korean, according to data pulled by researcher Andrew Griffith, based on a candidate database he created with The Hill Times, The Samara Centre for Democracy, and researcher Jerome Black, drawing from candidate biographies, media articles, social media, and photo analysis. The data may be missing some MPs, as it’s gleaned from publicly available information, and largely based on self-reported details.

Improving representation means striking a balance between “having candidates that run that reflect the composition nationally and yet making sure nominations are grassroots,” said Conservative MP-elect Marc Dalton, who is Métis and among the 10 MPs who identify as Indigenous in this Parliament.

Though a record number of 65 Indigenous candidates ran this election, the number who made it into the House didn’t budge from the 10 elected in 2015.

That amounts to three per cent of MPs, while 4.9 per cent of Canada’s population identified as Indigenous in the 2016 census. The party make-up has slightly changed, with six MPs in the Liberal caucus, two new MPs for the NDP, one Conservative, and Liberal turned Independent Jody Wilson-Raybould (Vancouver Granville, B.C.) remaining in the House.

The number of visible minority MPs is out also of line with the Canadian population, according to the 2016 census, which puts the visible minority population at 22.9 per cent—compared to 15 per cent of MPs in the 43rd Parliament. The Liberals lead with 38 MPs, followed by 10 in the Conservative Party, and three with the NDP. None of the Green Party’s three MPs or the Bloc Québécois’ 32 MPs are visible minorities.

If that’s the benchmark, Canada has “a serious underrepresentation problem,” said Mr. Griffith, a researcher at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute, who uses a narrower comparison, looking instead at the level of Canadian citizens, rather than residents, who are visible minorities—17.2 per cent.

In that respect, he said parties are doing “reasonably well” especially compared to other political systems.

There were also small gains in the number of visible minority candidates who ran overall this election, from 12.9 per cent of candidates running for the main parties in 2015, to 15.7 per cent, including the new People’s Party of Canada, which had more visible minority candidates than the Green Party.

As with women, Samara researcher Paul Thomas said there’s a similar problem with visible minorities being less likely to run in seats where parties have a strong chance of winning. Gains in diversity are more likely made through seats that open up each election when incumbents leave, said Mr. Thomas, but his analysis found that the most competitive seats weren’t as open to diverse candidates.

This was especially true for the Conservative Party, which ran three visible minority candidates out of 42 competitive ridings—those with no incumbent running for re-election, or which were lost by a margin of five per cent or less in 2015.

Mr. Thomas also noted the Bloc’s “very poor performance” on this front. Despite its caucus tripling in size, only four of its 78 candidates were visible minorities, none of whom were ultimately elected.

When breaking down the results by ethnic background, a better picture emerges, noted Mr. Griffith, one that shows clear gaps in federal representation by community. For example, Filipino-Canadians are the fourth-largest visible minority group, but parties fielded only four candidates with that background overall, and none were elected. At 1.5 per cent of the House, Black representation is also low, he said, with five elected of the 49 candidates nominated across the major parties, despite making up 3.5 per cent of Canada’s population.

Mr. Dong is one among a record eight Chinese-Canadians elected to Parliament this year, but he noted it’s still half what it should be to reflect the Chinese-Canadian population, which makes up 4.6 per cent of the country.

“I think all parties, when it comes to candidate searches, are stepping towards the right direction,” said Mr. Dong. “In the beginning, it’s always hard, but when you start generating interest” and bringing candidate numbers into the double digits, as was the case with his community this election, he said it means there’s less of a mystery to political candidacy, and that more will come. Based on Mr. Griffith’s assessment, there were 38 Chinese-Canadian candidates in the running this past election.

…