Don Kerr: Canada’s population growth is exploding. Here’s why

2024/04/27 Leave a comment

Good analysis but late to the party like a number of others:

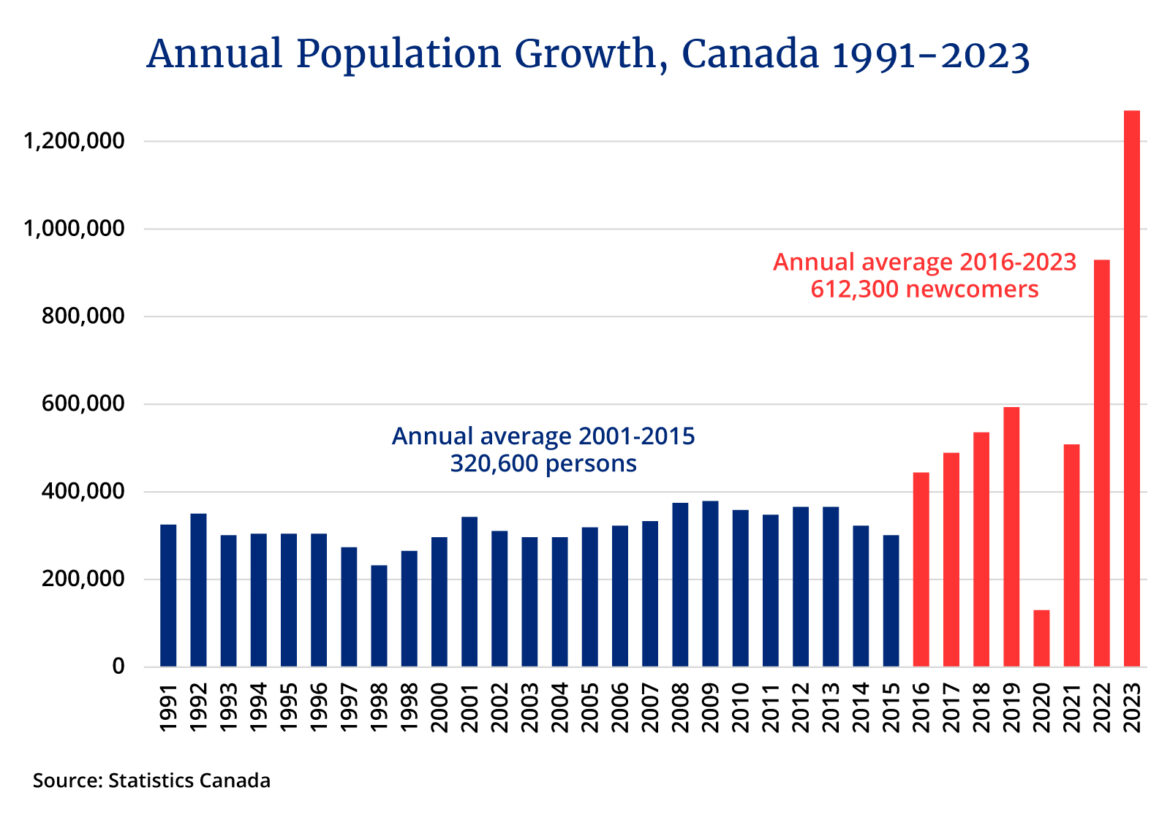

As a professional demographer who has carefully followed Canada’s demographic evolution over the past three decades, I am shocked by some of the most recent demographic data released by Statistics Canada. From 1991 through to 2015, the year in which the current government was first elected, the annual growth in Canada’s population grew in a predictable manner at an average of roughly 320,000 persons per year.

Following 2015, that growth has rapidly accelerated. Following a temporary dip in population growth due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Canada’s population growth reached just over half a million in 2021 (509,285 persons), close to a million in 2022 (930,422), and then an astronomical 1.27 million persons in 2023.

Put another way, whereas for several decades Canada’s population growth rate hovered at about 1.0 percent annually, this rate has more than tripled in a few short years, up to 3.2 percent in 2023.

In even starker terms, the 2023 rate of population growth is like adding a new Saskatchewan to Canada’s total population in slightly less than a single calendar year. As of 2023, there is not a single country in the G7 or in the OECD that has a population growth rate even close to Canada’s. Population growth in the U.S., for comparison, is currently at about 0.5 percent. Even prior to the recent upturn, Canada’s rate of population growth was actually the highest in the G7 and among the highest in the OECD.

Most astoundingly, in making international comparisons, Statistic Canada now points out that Canada in 2023 is among the 20 fastest-growing countries in the world, ranked beside several very high fertility countries, largely situated in sub-Saharan Africa. While Canada’s current population growth of 3.2 percent is obviously not sustainable, a constant growth rate of 3.3 percent would imply a doubling in Canada’s total population in under 25 years.

The last time Canada saw a growth rate comparable to this was fully 67 years ago. In 1957, Canada was close to the height of its baby boom, with a birth rate close to four births per woman. Slowly over decades this growth rate gradually declined as fertility rates fell (no abrupt shifts here).1

Most recently, Canada’s growth has almost entirely been the result of international migration (97.6 percent) as the rate of natural increase (births minus deaths) has continued to decline steadily. Hence, the pace at which Canada’s population grows, in a predictable manner, can be seen as a function of Canada’s immigration policy—meaning, then, that this is a policy problem that the federal government, in consultation with the provinces, can solve itself by setting and regulating immigration targets. This includes both permanent immigration (economic, family, and refugee classes) as well as the increase in non-permanent residents (international students, temporary work permits, and asylum claimants).

The question remains as to how we have gotten into this situation in the first place. When Sean Fraser was first appointed to the Trudeau cabinet as immigration minister in the fall of 2021, Canada’s growth rate was roughly 1 percent. By the time he was shifted from immigration to housing and infrastructure in the summer of 2023, Canada’s growth rate had climbed to its current heights. As many commenters have pointed out, it is somewhat ironic that the minister appointed to fix the issue of housing affordability was the minister of immigration who allowed this unprecedented growth in population.

In the summer of 2023 when Canada’s population was growing at a rate that had not been seen for almost 70 years, Fraser attempted to downplay the link between population growth and rising housing costs, saying that the solution to the country’s housing woes should not involve closing the door to newcomers.

The data from both Statistics Canada and the Canadian Housing and Mortgage Corporation (CMHC) belie the minister’s baffling assertion. Canada’s demographic growth has clearly outpaced its housing stock. Coming out of the pandemic, housing starts climbed to 271,000 in 2021, the highest number recorded for half a century, only to drop slightly in 2022 and 2023. In total, Canada witnessed about 800,000 housing starts over the 2021-2023 period, whereas over this same period, Canada’s population grew by over 2.5 million. The fact that the CMHC forecasts fewer than 224,000 starts in 2024 and only 232,000 in 2025 does not bode well for housing affordability in Canada, particularly in the context of continuing rapid population growth.

Having said all this, it seems that the federal government has finally woken up to this issue and is now committed to reducing this growth. Current immigration minister, Marc Miller, has made overtures towards slowing Canada’s population growth—even potentially back down to historically sustainable levels. Most importantly, Miller recently announced that the proportion of “non-permanent residents” (NPRs) in Canada will be reduced from its current level of fully 6.2 percent of the total Canadian population down to 5.0 percent over the next three years. For context, NPRs were only about 3.1 percent of Canada’s population in 2021. [mfnBy NPRs, the federal government is referring to international students, persons in Canada on temporary work permits, as well as asylum claimants.[/mfn]

As the government has already capped and reduced the number of international students, a sizeable share of this reduction will occur among persons with temporary work permits. Over 60 percent of Canada’s population growth in 2023 was a by-product of the increase in the number of NPRs. If immediately implemented, Canada could shift from admitting an additional 800,000 NPRs in 2023 to seeing a decline in the number of NPRs by perhaps -160,000 in 2024 (serving to reduce Canada’s rate of growth). Merely with this reform, and continuing with its current commitment to welcoming roughly half a million landed immigrants yearly over the next several years, Canada’s growth rate could return to sanity. The issue remains as to how successful the government will be in implementing this reform.

The dramatic shift in Canada’s rate of population growth has inevitably had important consequences, and not all of them positive. Take, for example, the increasing strain on the country’s already-burdened health and social services. In policy terms, a steady, gradual upturn in population growth is far better for planning future labour force, housing, and infrastructure needs.

Overall, Canada will be well served into the future by returning to and maintaining a predictable rate of population growth and avoiding the rather abrupt shifts experienced most recently. A majority of Canadians have long been supportive of Canadian immigration policy. The recent mishandling of this file has jeopardized this consensus. Hopefully not irreparably.

Don Kerr is a demographer who teaches at Kings University College at Western University. From 1992-2000 he worked in the demography division at Statistics Canada.

Source: Don Kerr: Canada’s population growth is exploding. Here’s why