Good in-depth account of how the Canadian immigration value proposition is becoming more shaky at best:

Should he stay or should he go? It was the question on Sanjay Gupta Sagar’s mind.

He had come to Canada six years ago, with the expectation that everything would fall into place.

The Nepalese man had a PhD. He had years of international research experience in public health and epidemiology. He had chosen to come to Carleton University in Ottawa as a postgraduate work fellow.

“I was flying high in my professional career,” says the 37-year-old. “There was nothing that could’ve stopped me from becoming a successful scientist and researcher.”

After a year, in 2019, riding his solid credentials, he, his wife and his son got their permanent residence in Canada. It was, it turned out, the easy part.

“After I completed my fellowship, that was the turning point,” he says.

Sagar struggled to find work in his field. He eventually got an administrative job at Statistics Canada, but he felt frustrated at not being able to use his training and education.

“I never would’ve thought I would have to struggle in my life professionally or financially,” he says.

He knew he was unhappy, but uprooting his family and leaving Canada? That was a tougher question — one without an easy answer.

It has been a question not just for Sagar, but for thousands of other newcomers, and for the policymakers striving to grow this country’s population.

Canada is in the process of welcoming a historic number of permanent residents — 465,000 in 2023; 485,000 in 2024; and 500,000 in 2025. But Canada is not the only country vying for skilled immigrants, and many highly educated and motivated immigrants who have come here are also leaving, in search of greener pastures.

A conservative estimate of 15 to 20 per cent of immigrants leave the country within 10 years, according to Statistics Canada.

But it’s rarely an easy decision to give up on the Canadian dream.

Do immigrants get a fair opportunity in Canada?

Sagar left Nepal when he finished his undergraduate studies in public health and moved to Missouri for postgraduate studies. His research interest would later take him across the United States and to Germany, South Africa and Australia.

Although he had never been to Canada, it seemed to be a great choice. It offered a clear and promising pathway for permanent residence via the work permit with his postgraduate fellowship.

A pioneering researcher in electromagnetic field exposure, Sagar was confident he would thrive in his adopted country and bought a three-bedroom condo in Ottawa shortly after his arrival.

But the harsh reality sank in soon after he finished his fellowship. He applied to more than 50 jobs related to public health but only got two interviews. Both were unsuccessful; one employer was looking for different skill sets, while the other had a better candidate.

“It was demotivating, frustrating and demoralizing,” says Sagar, who wasn’t sure of the reason why. “I’m not getting the right kind of job. Is there any problem in me or is it Canada?”

He started applying for jobs in the U.S. To his surprise, he says, calls for interviews started pouring in, though he always balked at taking up any job offer in the U.S. on a work permit without the safeguard of a green card.

“There are so many skilled immigrants who qualify to come to Canada, but once they end up here, many don’t get the opportunity for the jobs their skill sets are for,” he laments.

“You have engineers, doctors and dentists working in retail. That’s very strange to me.”

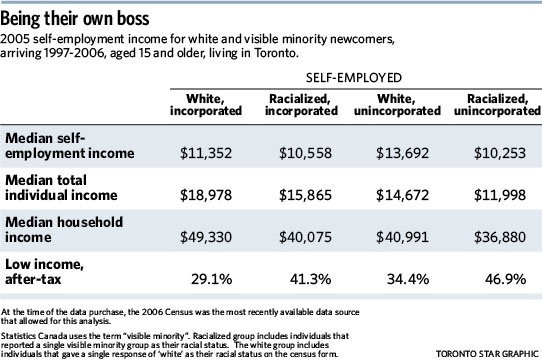

A recent Statistics Canada report found 34 per cent of immigrants selected via the economic category — a group selected for entry into this country due to their higher education and skills — were employed in lower-skilled jobs.

Even among longer-term economic immigrants who have been in Canada for more than a decade, 31 per cent were in these so-called survival jobs.

“We historically focused on the ‘front end’ of immigration, namely recruitment,” says Western University professor Michael Haan, whose research focuses on immigrant settlement, labour market integration and data development. “Nearly no research or policy attention has been given to keeping newcomers in Canada.”

“It is very expensive to identify the types of immigrants we want and need, recruit newcomers that fit the profile, process their applications and provide them with settlement services. To have them leave the country after all this work provides us with little to no return on this investment.”

Sagar, meanwhile, worried that the longer he settled in Canada with an unfit job, the more he would lose his aspiration to stay the course as a researcher.

His older son had grown comfortable in Canada, and now Sagar also had a Canadian-born baby daughter to feed.

Immigrants’ expectations have shifted

The issue of “deskilling” highly skilled immigrants is not new.

Successive waves of newcomers have struggled to get their foreign credentials accredited and satisfy employers’ preference for Canadian work experience.

Toronto Metropolitan University professor Marshia Akbar, who studies labour migration, says many immigrants who came in the 1980s and 1990s accepted the adversity and toiled in odd jobs to remain in Canada, because they believed they had no other option and their sacrifices would give their children a better future.

But their expectations seem to have shifted.

“For this generation of immigrants, they are not going to work in low-skilled jobs and wait for 10 years to catch up and get to work as an engineer or as a banker,” she says. “They get their residency but they don’t even wait for their citizenship.”

She says research suggests the country simply doesn’t have so many skilled jobs to go around.

A recent Statistics Canada report suggested there are no widespread labour shortages for jobs that require high levels of education as the number of unemployed Canadians with a bachelor’s degree or higher education since 2016 has always exceeded the number of vacant positions that require at least an undergraduate education.

Akbar knows a number of people who have left Canada after completing their PhDs because they couldn’t find a job and moved to the U.S. or returned home, where their Canadian education is highly regarded.

“In the contemporary situation, not just the traditional immigrant-receiving countries like the U.S., U.K. and Australia are looking for highly skilled migrants. Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, U.A.E. and every country are all waiting to receive highly skilled migrants,” she says.

“We have a higher cost of living. We pay higher taxes. These are all the reasons why many newcomers are not happy in Canada.”

And that seems to be supported by a national survey released in April by Leger for the Institute of Canadian Citizenship that found 30 per cent of newcomers below age 35, and 23 per cent of university-educated new immigrants, are planning to relocate within the next two years.

Citizenship rate declining

Among the worrying signs when it comes to Canada’s immigration success story is the fact that the citizenship rate among immigrants has been declining for years.

The 2021 census found that just 45.7 per cent of permanent residents became citizens within 10 years, down from 60 per cent in 2016 and 75.1 per cent in 2001.

The two countries from which Canada gets the most immigrants — India and China — don’t recognize dual citizenship. That has likely had an effect on Canadian citizenship uptake as newcomers are afraid Beijing and Delhi will strip their Chinese and Indian citizenship.

Critics have linked the decline with measures brought in by the former federal Conservative government that were meant to tighten citizenship requirements.

However, it could also be an indication of the devaluation of Canadian citizenship.

Feng Hou, principal researcher of the statistics agency, says data has shown immigrant out-migration from Canada generally surges during recession years. That’s indicated by the decline in immigrant income tax filing — a default indicator of a person’s presence in Canada in the absence of official exit and entry records.

Among the different classes of immigrants, he says the ones least likely to stay are those who are the most educated and here for economic opportunities; who came under the federal skilled workers program; and immigrants from the U.S. and Western Europe.

“We need to have a better understanding of why immigrants leave Canada,” says Hou, adding that a Canadian passport does offer skilled immigrants further mobility without the hassles for visas.

“Are they just using Canada as a stepping stone? Are they moving to the U.S., where there are more opportunities, or are they returning home?”

A lack of ‘Canadian experience’

Komal Makkar, who is in her 30s, had never been to Canada before she landed in Toronto in January 2021. But back home in Punjab, she was raised surrounded by billboards and signs that painted the country as a land of opportunities.

The architect who hailed from India had worked in Dubai since 2016 and developed a niche in multiple international projects in Africa, India, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, designing state-of-the-art hospitals.

But trying to get citizenship in Dubai was close to impossible. To move to the U.S., she would need an employer to sponsor her visa. Canada seemed a good choice as her education and work experience would get her direct entry for permanent residence.

She knew there could be initial struggles to find her footing and she thought she was prepared.

Makkar and her husband, also an architect, were excited to find a permanent home in Toronto. The winter snow was pretty. The air was fresh. The people were friendly. The vibe of the city was amazing.

The career-oriented couple hit the ground running as soon as they found a temporary home subletting someone’s one-bedroom apartment. But they were daunted by the advice of job counsellors at various immigrant serving agencies.

She was advised to remove her master’s degree from the resumé and shave off some years of her work experience and high-profile projects in her reference, so she wouldn’t be overqualified for entry-level positions. Suggestions were also made for them to explore job options that use their skills in other ways.

“We applied for so many jobs. But most of them were asking for Canadian experience,” says a frustrated Makkar, who was instead offered architectural technician positions at minimum wage. Others offered co-op or unpaid internships for the elusive work experience.

With their savings quickly depleting, she and her husband were faced with the choice of paying hefty tuition fees to go back to school for more certifications or just settle for low-paying jobs that wouldn’t allow them to build a life and home here.

While the cost of living is high in Dubai, it offered Makkar and her husband the financial and professional security that Canada didn’t.

“I was already working up the ladder. I was working on big projects. My goal was to go for even bigger projects. Should I start again from where I started?” Makkar asks. “We don’t see this country as a permanent home.”

After two months, she and her husband made what she called “an unexpected decision” to return to Dubai. Despite the $4,000 she spent in getting all the papers and in fees for their permanent residence application, she says it was the best decision.

“I’m happy in what I’m doing. I love what I’m doing. I don’t have to throw something out of experience,” says Makkar. “I respect myself too much to stay in Canada.”

‘Skill sets in IT are easily transferable’

Harman Singh Dhaliwal was among the fortunate immigrants whose technical skills in IT happened to be in short supply when he arrived in Toronto in February 2018, before living costs went through the roof.

He and his wife, who also worked in IT in India and in the U.S., found jobs in their field within a month, though their positions were one notch below their years of work experience. But that allowed them to soon buy a home in the city.

“The skill sets in IT are very easily transferable,” says the 35-year-old, who took three years to get promoted to be a technical lead at work. “They are the same whether you work in Mumbai, Shanghai, L.A. or Toronto.”

Dhaliwal says he and his wife were not desperate to leave India and were simply looking for a different lifestyle in North America, where the living standards are higher and air quality and environment are much nicer.

Having access to good jobs is a starting point to keep top talents in Canada as people now have options in China, India and the Gulf countries and can afford to be picky, says Dhaliwal, who became a father last year and is now a Canadian citizen.

Current economic immigration policy favours applicants under 30, with points awarded for age progressively decrease every year. The younger demographics, he says, have fewer obligations, which makes it easier just to pack and leave if they have the sought-after skills.

“When you have a family of your own, you are married and your kids are in school, you live in a nice neighbourhood, own your home, it’s very difficult to leave all of that behind,” says Dhaliwal.

While Canada is focusing on the quantity of immigrants it’s bringing in, he says it must pay as much attention to the quality of opportunities available for newcomers and make sure they have the supports for new ideas and innovations.

“I think we are attracting a lot of top-tier talent but we end up not giving them the top-tier opportunity or the platform to utilize their talent,” he notes. “I never felt I was bound to Canada, but I got a job in the first month and we bought a house. We’re now very focused on settling our life over here.”

How to retain immigrants

The value of Canadian immigration became a heated debate recently in a Facebook group run by Toronto immigration consultant Kubeir Kamal. The group has half a million followers, and someone posted a question to them about whether Canada offered what they came to this country for.

Kamal says he was surprised that there were more people who were willing to go back or have already returned to where they came from than those who would stick it out. He says many cited the high costs of living and the challenges to maintain the lifestyle they used to enjoy while struggling to secure jobs.

“That was quite an eye-opener even for me,” says Kamal, host of Ask Kubeir on YouTube, which has 80,000 subscribers. “The charm of the first-world passport is very quickly fading away.”

Retention efforts, according to Kamal, should focus on those who show the desire to be here and have established themselves, which mean they have more incentive to stay.

He points out there are more than 1.5 million temporary residents such as international students and temporary foreign workers in Canada, but only a fraction have a shot at permanent residence.

Meanwhile, the bar for permanent residence is extremely high for those who immigrate directly from abroad, without the benefits of Canadian education credentials and work experience.

Most of these newcomers, says Kamal, would be 30 or under, with a master’s degree and good English, plus several years of international work experience to meet the permanent residence requirements.

“When they come to Canada, it is a shock in terms of the cost of living, the lifestyle. It’s not remotely anticipated for them,” he says.

As a result, some may stay until they get their citizenship and others may leave their spouses and children in Canada and return to their careers in the United Arab Emirates or their country of origin so they could financially support their families here.

Even though the federal government has recently launched a program to target immigration applicants with skills in demand in the country to better align newcomers with Canada’s labour market needs, Kamal says it won’t work without the proper support to help them overcome the lack of Canadian experience and credential recognition, and in professional licensing processes.

“This would fall flat if you don’t back it up by providing accreditation or an easy route to accreditation for these people to practise in Canada,” he says. “If you don’t make it conducive for them to find meaningful employment in Canada, you will end up losing them.”

Opportunity found — in the U.S.

In Ottawa, Sagar, the Nepalese PhD, had a full-time contract job first as a statistical assistant and later an analyst while his wife worked as a retail clerk. When their daughter was born in the summer of 2021, he decided to take a year off to contemplate the family’s future.

He knew he was deeply unhappy in Canada and decided to revive his stalled career as a research scientist. With his PhD credentials, he successfully applied for an American green card last June.

In September, he moved to St. Lawrence County, N.Y., and worked as an epidemiologist. In March, he made another move to Lebanon, N.H., into a managerial position in public health, to be followed by his wife and children after this school year.

When he recently sold the three-bedroom condo they bought in Ottawa in 2018, the value of the property actually doubled.

“I actually made more money selling my house than all I’d earned in my time in Canada,” says Sagar, who is now a citizen.

“Immigrants are not coming to Canada with the aim to become super-rich. They just want to have the right kind of jobs and they would be happy to stay and raise their family there.”

Source: ‘I respect myself too much to stay in Canada’: Why so many new immigrants are leaving