A number of weak commentaries trying to change the narrative on immigration and pressures on housing (along with healthcare and infrastructure). None of these address the time lags in approving new housing.

Starting with the more intelligent analysis by Carolyn Whitzman, who notes the policy failures in housing policies (but fails to recognize the failure of immigration policies) and the need for better data:

As the country’s housing crisis intensifies, there’s been a lot of finger-pointing: at foreign investors snapping up residential real estate, at municipal governments and prohibitive zoning by-laws, and now, at immigrants and international students, the latest group thrust into the spotlight for exacerbating the crunch.

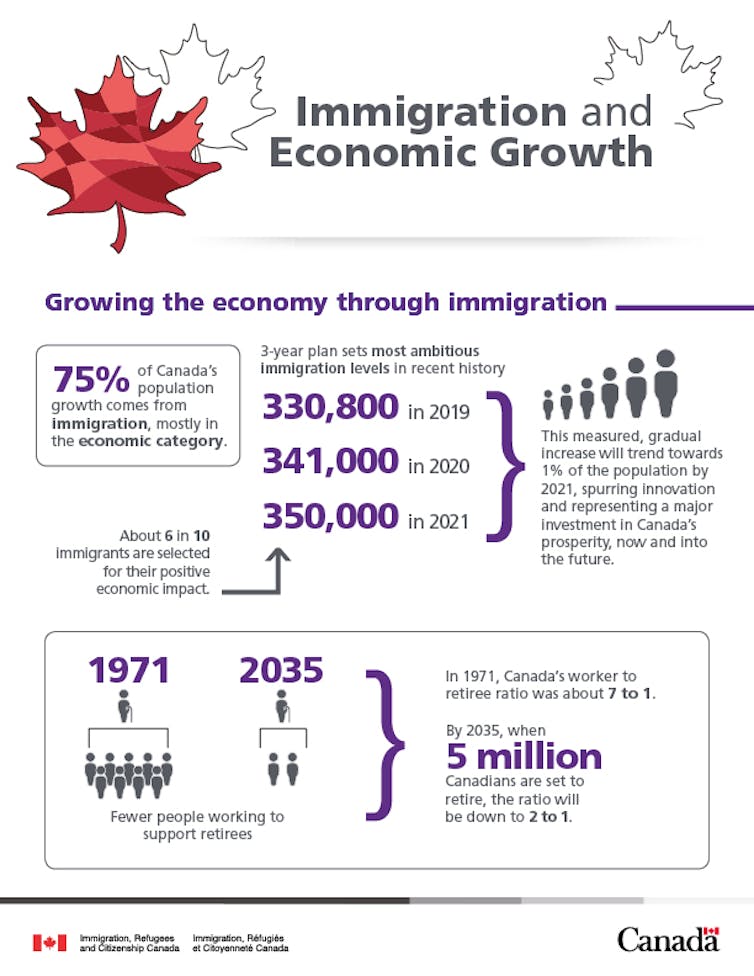

Canada is, by far, the fastest-growing country in the G7. We passed the 40 million mark in June, after the population surged by over a million in 2022. Nearly all of those new Canadians were temporary and permanent immigrants. The international student population has also skyrocketed—we’re on track to welcome 900,000 international students this year, three times as many as in 2013.

Although Canada’s major political parties have been careful not to blame newcomers for housing challenges, Immigration Minister Marc Miller said that “volume is volume, and it does have an impact,” in reference to the influx of immigrants. The federal government, which is not backing down from its recently increased annual target of 500,000 new permanent residents by 2025, is also considering a cap on international students as a way to ease the pressure.

But limiting immigration isn’t the solution, says Carolyn Whitzman, housing policy researcher at the University of Ottawa and expert adviser to the University of British Columbia’s Housing Assessment Resource Tools project. In fact, since current estimates of housing need don’t take into account millions of Canadian residents, as well as projected newcomers, we have a woefully uninformed picture of the situation. “Immigrants are an easy target,” says Whitzman. We spoke to her about why we’re so eager to shift the focus to immigration, the dearth of data on who actually requires housing, and the urgent need for a national social housing program.

A growing chorus of people are openly blaming immigration for the housing crunch. What’s your take?

Even if Canada stopped immigration tomorrow, we still couldn’t serve the population who live here. Nearly 1.5 million Canadian households are in what’s called “core housing need,” which refers to households that are living in unaffordable, overcrowded or otherwise uninhabitable homes, where an affordable and adequate home is not available in their area. Millions of other Canadians—homeless people, students, people in congregate housing like long-term care and group homes—aren’t even factored into core housing need. How will their need for low-cost homes be helped by restricting immigration or foreign students? Where’s the evidence? Immigrants and international students are an easy target.

An easy target, sure, but won’t ever-increasing numbers of permanent residents and international students put additional strain on the housing market?

Yes. So will the formation of new households, including young adults moving away from home or couples divorcing.

Why has the focus of the housing crisis conversation shifted so abruptly to immigration?

It appears to me to be a sign of desperation. Immigrants have always been blamed for the housing crisis. Look back 100 years and people were against building boarding houses because they were scared of foreigners moving in and endangering their families. Nowadays, politicians are blaming foreign investors for housing shortages, too. I’m very impatient about people pointing fingers at immigrants for the housing crisis, because it has very little to do with immigration and a lot to do with government policy.

Which government policy?

That’s the problem—there hasn’t been a national housing policy since the early 1990s. That’s when the federal government decided it was a provincial or territorial responsibility, and in the case of Ontario, the province punted it to municipalities. There are more and more international students each year who need places to live, but colleges and universities are provincially regulated. Immigration, on the other hand, is a federal responsibility. There needs to be coordination between federal, provincial and municipal governments. And that needs to start with an accurate sense of who needs housing, where, and at what price.

Do we have that information?

Partially. We know that new migrants are among the groups most likely to be in core housing need. Our data from UBC’s Housing Assessment Resource Tools project shows that in 2021, 16 per cent of new migrant households—those who moved to Canada since the last census in 2016—were in core housing need. That’s higher than the Canadian average of 10 per cent. Refugee claimants were the most likely households to be in core housing need, almost one in five. But the census only tracks housing need in private, non-farm and non-student households.

So we don’t have data on students?

No. The federal government has zero information on student housing needs, international or otherwise. In 1991, when the measure for core housing need was created by the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) and Statistics Canada, the decision was made to leave out students because it was considered a “temporary situation of voluntary poverty.” As a result, we don’t have any information on what students can afford to pay, whether they’re overcrowded or living in mouldy basement apartments. That’s unusual for a developed economy like Canada. France, Finland, the Netherlands, Germany—every country I know of with strong non-market housing programs builds student housing into it.

Why the lack of data?

I think it goes back to the ’90s, again, when the federal government backed out of housing policy. It’s been three decades of people passing the buck.

A classic tale of Canadian federalism.

I won’t disagree with you there.

And yet the federal government is looking into a possible cap on the number of permits issued to international students.

I believe we need evidence-driven policy instead. A good example is the Rapid Housing Initiation, which was first proposed as a COVID-19 relief measure in 2020. The initial target was 3,000 very affordable, rapidly constructed (or renovated) homes for the homeless. About 4,700 homes were constructed or under construction within 18 months. It was renewed in 2021 and 2022—the total number of units created is expected to be over 15,500 units. It needs to be an ongoing program.

The Liberals did introduce a national housing strategy in 2017, which promised to restore Ottawa’s involvement in building social housing. And legislation was passed in 2019 designating housing a human right.

Sure, but look at the national housing strategy. It literally has nothing to say about students. Do they not exist? Are they not part of the housing market?

You mentioned the fact that new migrants are more likely to be in core housing need. How else are they impacted by the housing crisis?

Asylum-seeking families, for instance, tend to be larger households, and there’s a critical shortage of rental housing that has three bedrooms or more. Also, new migrants traditionally moved to the inner city, where there are social services and other resources. But there’s no affordable housing there anymore, so migrants are moving to areas that aren’t near services or jobs or public transit, and most don’t have Canadian driver’s licences on arrival. All that exacerbates settlement issues, like isolation and unemployment. The federal government needs to think about an integrated policy between immigration and housing.

It sounds like you’re on the same page as Public Safety Minister Dominic LeBlanc, who said that the government should “tailor its policies on immigration and housing to acknowledge the link between the two.” What would that look like?

For one thing, we’d be able to project population increases over the next 10 years. Remarkably, the 2017 national housing strategy we’ve referred to has targets that don’t include the impact of population growth through immigration.

The CMHC projected that we’ll need 5.8 million homes by 2030 to reach affordability. Do figures like that take immigration into account?

They don’t, though I do know that the author of that report is planning to publish a follow-up to revise that figure in light of current immigration projections. We can’t plan for housing if we don’t know how many people are coming in. Canada is a rich country and a smart country—we have the highest rate of individuals with higher education in the world. So if we’re a rich, smart country, and we can’t solve the housing crisis, what are we even doing?

Speaking of solving it, you’ve got a new book coming out next year, How to Home: Fixing Canada’s Housing Crisis. Spoiler alert, but how do we fix it?

We need a calculation of supply shortage that doesn’t just tell us we need X million units, but actually gets into what kind of housing and where. We have one of the lowest rates of social housing in the world. And we’re going to have to scale up purpose-built rentals, rather than condos, again. That kind of fell off the cliff in the ’70s. Back then, during another period of high immigration, we were literally building more housing than we are today because we had a national housing social housing program and purpose-built rentals.

What is one pragmatic step the government could take?

Enable purpose-built rentals again, with some conditionality. In other words, you can’t have a 30-storey building in the middle of the Greenbelt, for instance. There needs to be some conditions around location, price point and environmental sustainability. There were measures in place in the ’60s and ’70s that led to the construction of most of our current purpose-built rental stock—meaning most apartment buildings are 40 to 60 years old, which is a whole other problem. But we need a social housing program. We haven’t had one for three decades, and we’re seeing the impact of that.

Is a federal social housing program in our future, realistically?

Absolutely. The federal government promised a new co-op housing strategy in the 2022 budget. Sources tell me it’s ready to roll. I’m not sure why it hasn’t yet, but every single major federal evaluation of the national housing strategy has asked why a non-market, social housing program isn’t part of the plan. Everyone from Scotiabank on down is saying you need to start by doubling social housing. It’s the most direct way to start building the housing that people need most.

How do we quickly build a lot of homes?

In the post-war period in Canada, housing patterns were used—the CMHC literally had Type A, Type B, Type C stamped on the front of their “victory houses.” That happened in Sweden, too, with the Million Homes Program in the 1960s and ’70s. Kitchens and bathrooms of a predetermined size were built off-site. That helped streamline construction—and led to the pre-eminence of Ikea, by the way. There are currently a whole bunch of modular housing providers who have expanded with the new rapid housing initiative, and that’s a positive thing Canada could export. There’s a big advantage to going modular and building off-site, particularly in northern climates where the construction season is shorter. It’s really problematic if construction workers can’t afford to live in the cities they’re building.

Last year, Canada’s purpose-built rental apartment vacancy rate hit 1.9 per cent, its lowest level since 2001.

The best metaphor I can think of is the credits from The Simpsons, where everyone’s running for a seat on the same sofa. We have students running toward the sofa, seniors looking to downsize running toward the sofa. People who would have been able to buy homes in a previous generation are also in the race. So if we want everybody to have a seat, we need to build more sofas and make sure that they’re the right kind.

Anna Triandafyllidou argues that the housing needs can be accommodated by basement apartments and rooms but without any supporting data on their availability or the degree to which it helps homeowners pay their mortgages.

In recent months there has been a heated debate about Canada’s housing affordability crisis and the role of international students in the mess.

Some argue that, particularly in Canada’s big three (Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver), international students drive up rents because they are prepared to rent rooms in larger apartments or houses, and even share rooms with flatmates, bringing the overall possible rent of a unit to levels that are totally unaffordable for a local family.

In many smaller cities and towns, the sheer numbers of international students are also said to put pressure on housing, as there are simply not enough units for rent, regardless of the cost.

The question thus arises whether the average Canadian family is worse off because international students are creating an impossible rental market.

It is my contention that this is not the case, and I would actually argue the opposite: International students are saving both the average Canadian homeowner (and mortgage holder) and the Canadian banking system. How is that?

International students are high-paying and often exploited tenants in basement apartments and spare bedrooms across Canada’s large and smaller cities. Some are indeed contributing to competition in the market. But the housing crisis began long before the current surge in international students, and many of them, rather than competing with domestic renters, are living in arrangements that Canadians would not be seeking anyway.

Moreover, the rents that international students pay are allowing Canadian families to survive the Bank of Canada’s string of interest-rate hikes and their galloping mortgage payments. This, in turn, helps the banking system, as it grapples with the rising risk of defaults.

Recent reports show that, as the central bank tries to tame inflationwith higher borrowing costs, several Canadian banks have allowed borrowers to extend their mortgage amortizations to more than 55 years in an effort to keep the loans afloat and allow households to keep up their payments.

Anecdotal evidence suggests many families are renting not only their basements but their bedrooms to international students. In many cases, parents and children have squeezed into one or two rooms to leave the spare rooms for renters. Networking often works through friends and extended family, as many homeowners prefer to have a student from their own ethnic and/or linguistic background, to make sharing the home easier for everyone.

These rentals play a crucial and still unaccounted role in keeping households afloat now that their mortgage payments have grown sharply in less than a year.

While this is not a long-term solution for the housing affordability crisis, nor a strategy for international student migration, these insights point to a few ideas that could help in the short and medium terms.

Colleges and universities should be asked to arrange affordable accommodations for their incoming international students as part of the study permit application process. Such accommodation arrangements can include tailored schemes where, for instance, seniors are paired with students, offering full board for a reasonable price while the student helps by doing chores and grocery shopping or befriending the older person.

Young families could also be paired with international students and receive tax breaks on the rental income they make.

Provincial governments should provide strong incentives for colleges and universities to build more student residences.

International student migration needs to be reconsidered in Canada in some ways. We need to identify both bad practices (such as overexploiting international student streams as a revenue and sustainability strategy with little educational value) and bad actors (brokers and postsecondary institutions that prey on international students and their families, selling false promises for a path to migration). We also need to offer adequate services and protections to international students, including access to health care and clear pathways to job prospects.

But we must remember that international students are not the cause of Canada’s housing crisis – and that many households would be a lot worse off without them.

Anna Triandafyllidou is the Canada Excellence Research Chair in Migration and Integration at Toronto Metropolitan University.