Marche: ‘Acute, Sustained, Profound and Abiding Rage’: Canada Finds Its Voice

2025/08/11 Leave a comment

Good op-ed. But more needed in right and Trump-leaning media…:

The mind-set of Canada is changing, and the shift is cultural as much as economic or political. Since the 1960s, Canadian elites have been rewarded by integration with the United States. The snipers who fought with American forces. The scientists who worked at American labs. The writers who wrote for New York publications. The actors who made it in Hollywood. Mr. Carney himself was an icon of this integration as chair of the board of Bloomberg L.P., the financial news and data giant, as recently as 2023.

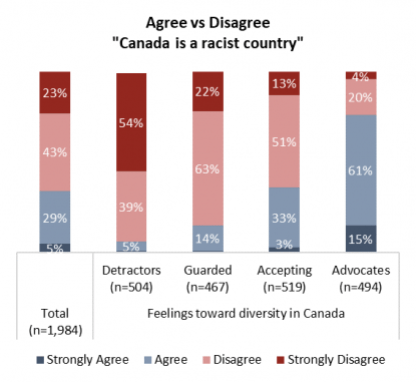

As America dismantles its elite institutions one by one, that aspirational connection is dissolving. The question is no longer how to stop comparing ourselves with the United States, but how to escape its grasp and its fate. Justin Trudeau, the former prime minister, used to speak of Canada as a “post-national state,” in which Canadian identity took second place to overcoming historical evils and various vague forms of virtue signaling. That nonsense is over. In several surveys, the overwhelming first choice for what makes the country unique is multiculturalism. This, in a world collapsing into stupid, impoverishing hatreds, is the distinctly Canadian national project.

Even after Covid and the failure to create adequate infrastructure for new Canadians, which lead to a pullback on immigration, Canada still has one of the highest rates of naturalization in the world. This country has always been plural. It has always contained many languages, ethnicities and tribes. The triumph of compromise among difference is the triumph of Canadian history. That seems to be an ideal worth fighting for.

Canada is now stuck in a double reality. In a recent Pew Research Center survey, 59 percent of Canadians identified the United States as the country’s top threat, and 55 percent of Canadians identified the United States as the country’s most important ally. That is both an unsustainable contradiction and also a reality that will probably define the country for the foreseeable future. Canada is divided from America, and America is divided from itself. The relationship between Canada and America rides on that fissure.

Margaret Atwood was, and remains, the ultimate icon of 1960s Canadian nationalism and also one of the great prophets of American dystopia. “No. 1, hating all Americans is stupid,” she told me on “Gloves Off,” a podcast about how Canada can defend itself from America’s new threats. “That’s just silly because half of them would agree with you,” and “even a bunch of them are now having buyers’ regret.”

Large groups of people in Canada, and one assumes in America, too, hope this new animosity will pass with the passing of the Trump administration. “I can’t account for the rhetoric on behalf of our president,” Gov. Janet Mills of Maine said recently on a trip to Nova Scotia. “He doesn’t speak for us when he says those things.” Except he does. The current American ambassador to Canada, Pete Hoekstra, is the kind of man you send to a country to alienate it. During the first Trump administration, the State Department had to apologize for offensive remarks he made, which he had at one point denied. He has also said the administration finds Canadians “mean and nasty.” Such insults from such people are a badge of honor.

But it’s the American system — not just its presidency — that is in breakdown. From the Canadian side of the border, it is evident that the American left is in the middle of a grand abdication. No American institution, no matter how wealthy or privileged, seems willing to make any sacrifice for democratic values. If the president is Tony Soprano, the Democratic governors who plead with Canadian tourists to return are the Carmelas. They cluck their disapproval, but they can’t believe anyone would question their decency as they try to get along.

Canada is far from powerless in this new world; we are educated and resourceful. But we are alone in a way we never have been. Our current moment of national self-definition is different from previous nationalisms. It will involve connecting Canada more broadly rather than narrowing its focus. We can show that multiculturalism works, that it remains possible to have an open society that does not consume itself, in which divisions between liberals and conservatives are real and deep-seated but do not fester into violence and loathing. Canada will also have to serve as a connector between the world’s democracies, in a line that stretches from Taiwan and South Korea, across North America, to Poland and Ukraine.

Canada has experienced the second Trump administration like a teenager being kicked out of the house by an abusive father. We have to grow up fast and we can’t go back. And the choices we make now will matter forever. They will reveal our national character. Anger is a useful emotion, but only as a point of departure. We have to reckon with the fact that from now on, our power will come from only ourselves.

Source: ‘Acute, Sustained, Profound and Abiding Rage’: Canada Finds Its Voice