Ifill: Bureaucratic efforts are just ‘diversity’ icing on a white cake

2023/11/09 Leave a comment

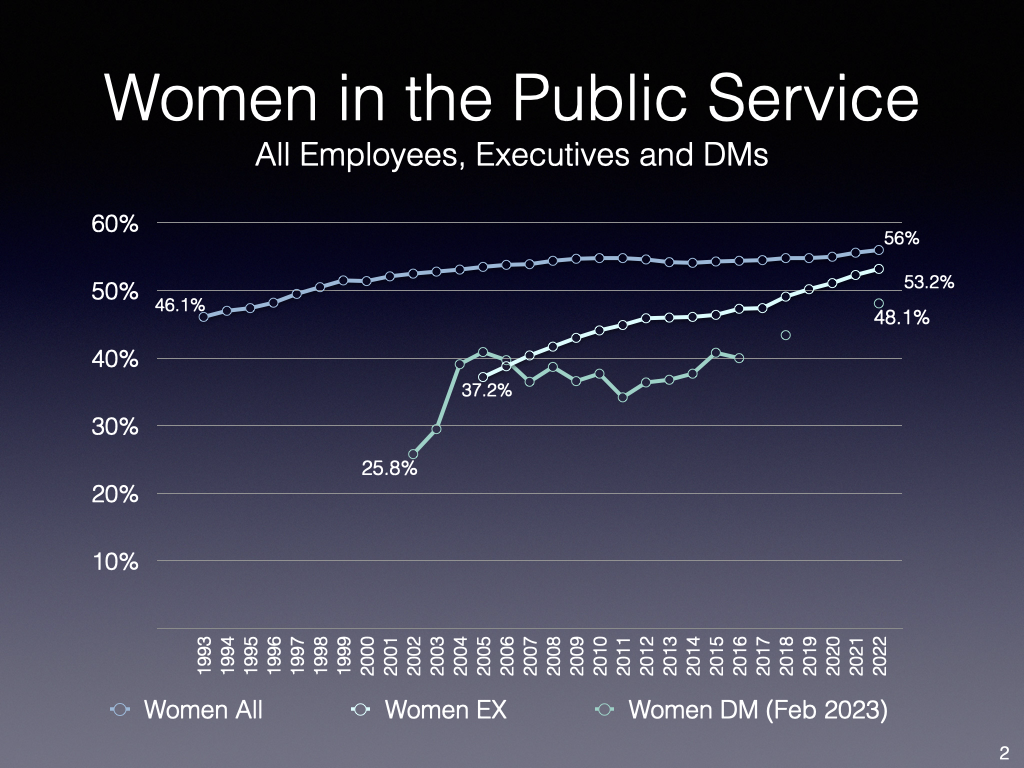

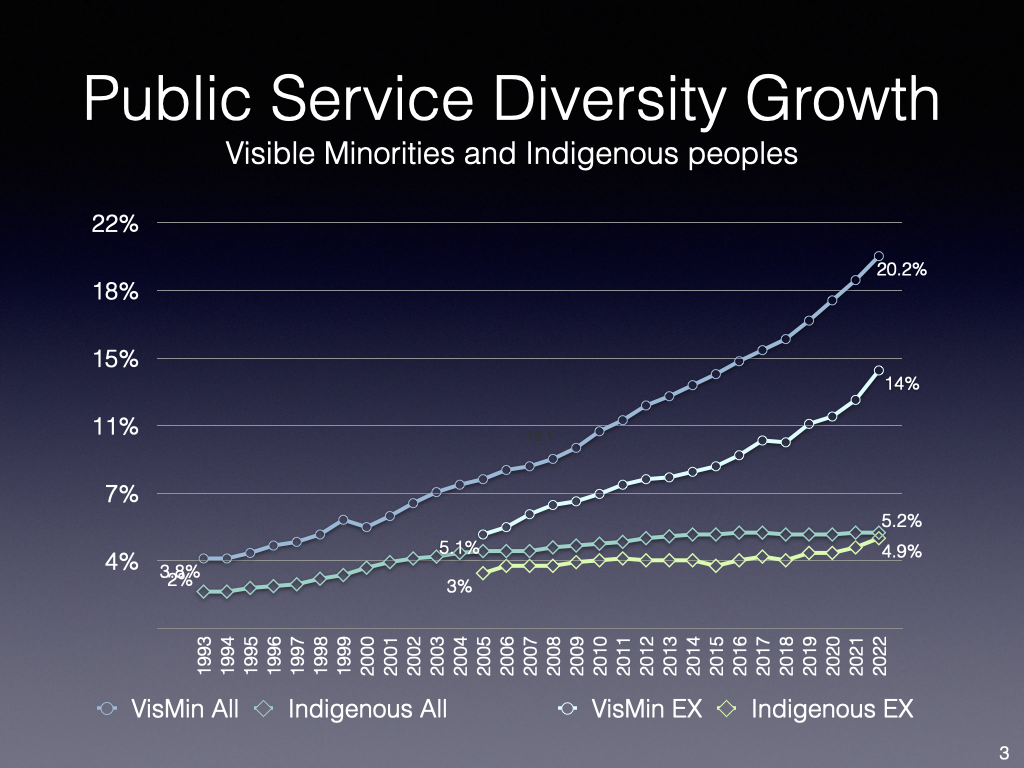

The overall data, of course, shows marked improvement in the past six years in which desegregated data by equity group, particularly for visible minorities and within visible minorities, for Black public servants including executives.

Somewhat unserious to ignore this data…

Calling for DMs to be replaced may feel good but is unrealistic, and she clearly has little understanding about how government and the public service work and that change, albeit too slow for some, occurs within a bureaucratic context.

As for the call for action, I also tend to be somewhat cynical as it appears to be adding yet another reporting requirement and it is too early to assess whether it has moved the needle beyond process:

In the months following the murder of George Floyd in 2020, and the global protests against police brutality and anti-Black racism that lasted the summer of that year, every corporation and government agency vowed to improve the economic lot of Black people by introducing watered-down diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) practices. Naturally, I was skeptical, considering my own experiences in the public service with anti-Black racism. I knew that nothing but transformative change led by Black and Indigenous people would suffice. As I wrote in this paper in February 2021, the Privy Council Office clerk’s effort was “a diversity and inclusion endeavour, dressed up as anti-racism. Devoid of an accountability framework, it makes no tangible effort to interrogate the systems that perpetuate racism.”

Two-and-a-half years later, the anti-Black racism measures the Liberals introduced for the public service are as good as six feet under. In the 2021 mandate letter to then-Treasury Board president Mona Fortier, the prime minister directed her to establish “a mental health fund for Black public servants and supporting career advancement, training, sponsorship and educational opportunities.” A year later, Black public servants involved in the fund blew the whistle on the racism they experienced while working on an anti-racism measure. As the Canadian Press reported last December, “The Federal Black Employee Caucus [FBEC] sent a letter to the Treasury Board’s chief human resources officer this month saying the workers supported efforts to address racism within the public service, only to be ‘continuously faced with the crushing weight of it.’”

I feel for those who worked so hard to make these initiatives happen. Countless hours and emotional labour have been added to the workload of many racialized employees for free, only for them to experience more racism. The CBC reported on the treatment of Black employees as outlined in FBEC’s letter to the Treasury Board Secretariat: “The email alleges that senior Treasury Board Secretariat officials created a toxic workplace culture. When the Federal Employee Black Caucus members pushed back, the email states, they were met with micro-aggressions and ‘character assassinations.’”

And those experiences bear out in evidence provided by the auditor general.

On Oct. 19, Auditor General Karen Hogan tabled the semi-annual report on performance audits of the public service—and government writ large—to the House of Commons in a series of nine parts. Report 5 looked at Inclusion in the Workplace of Racialized Employees, and it is not kind. It determined that “Canada’s efforts to combat racism and discrimination in major departments and agencies are falling short,” as reported by the Canadian Press. The AG selected a sample of six organizations“responsible in whole or in part for providing safety, the administration of justice, or policing services in Canada. Together, they employ about 21 per cent of workers in the federal core public administration.” Note that 20 per cent of the public service is racialized.

Let’s look at the highlights from the report:

- Racialized employees reported rates of discrimination at least 30 per cent higher than non‑racialized respondents;

- The organizations all established DEI plans to correct the conditions of disadvantage experienced by racialized employees, but failed to develop and institute accountability measures (I called this: “A system without accountability is a corrupt one, and in this system there is no justice”);

- They failed to collect or use data to assess progress on their plans, and failed to create, assess and implement key performance indicators; and

- No specific initiatives in action plans to address concerns and complaints related to barriers to raising instances of racism.

So basically, the public service wasted everyone’s time with this theatrical performance of DEI icing on a white cake, as I said they would. But it’s no surprise considering that we’re led by a performative government.

Furthermore, if the public service has discriminated against you, the institutions set up to “help” you only double down on that discrimination. As the Canadian Press reported in March, “The Treasury Board Secretariat found last week that the Canadian Human Rights Commission [CHRC], whose mandate is to protect the core principle of equal opportunity, discriminated against Black and racialized employees.”

Remember the Black Class Action lawsuit? The Trudeau government is still trying to ignore the problem by refusing to negotiate while attempting to get the case dismissed. In response to the CHRC discriminating against Black employees, the Class Action Secretariat said, “It also raises concerns about the CHRC’s capacity to offer justice to the broader experiences of Black workers across the entirety of the federal public service who share similar stories and experiences for over 50 years.”

This is how racism is systemic, systematic, and institutional. I have written about how racism within institutions carries over into public policy. Remember the three words: “the dirty 30.”

There is no reason to trust these corrupt systems that are intended to keep Black and racialized employees in subservient positions to white, male, heterosexual power. Deputy ministers have shown us, through action, that they are unserious “leaders” who are comfortable with overseeing abusive, toxic environments that increase the burden of performance on their employees, according to race. Seems discriminatory in itself.

Those who do not follow the directives from mandate letters and budget direction are committing insubordination, and are undermining political decisions. They should be removed from their positions. Deputy ministers are only supposed to oversee the implementation of policy; they are unelected administrators, not representatives elected by the people. Therefore, their decisions cannot supersede those political directives. Do we really want deputy ministers quietly subverting democracy just because they don’t like particular groups of people?

Source: Bureaucratic efforts are just ‘diversity’ icing on a white cake