Usual over the top rhetoric and expectations. Good that reporting is including relevant data from the PSES and EE representation data.

For Thompson to claim that PCO is not providing the numbers, these are available in Table 1 in the annual reports, albeit not disaggregated by visible minority or indigenous group or level.

Given the relatively large numbers (March 2023, 252 visible minority employees, or 22.8 percent), it should be possible to request and obtain disaggregated numbers for most groups, and for the larger groups, executives):

…The report—released on July 29 by the Coalition Against Workplace Discrimination, which obtained the document through an access to information request—said that Black, racialized, and Indigenous employees experienced “racial stereotyping, microaggressions, and verbal violence,” and a workplace culture where that behaviour is “regularly practiced and normalized, including at the executive level.”

The report also found that PCO’s culture discouraged reporting and that “effective accountability mechanisms are currently non-existent.”

Rachel Zellars, an associate professor at St. Mary’s University, produced the report following interviews she conducted with 58 employees from November 2021 to May 2022 as part of the PCO’s “Your Voice Matters” Safe Space Initiative, and her work as the inaugural Jocelyne Bourgon Visiting Scholar for the Canada School of Public Service.

Zellars said she conducted 13 interviews with racialized employees and eight with Black employees, the latter accounting for half of the total Black employees in the PCO at the time.

Those employees shared experiences of their managers and supervisors using the N-word “comfortably” in their presence, and expressing surprise and ignorance when informed it was a pejorative term, as well as Islamophobic remarks and “feigned innocence” when white employees were promoted over them.

In contrast, white employees had worked at PCO for longer periods, and were clustered in higher-level positions than Black, racialized, and Indigenous employees. Those white employees also detailed experiences and career-advancing opportunities “in stark variance” to their non-white colleagues.

The Safe Space Initiative was launched following a Call to Action by former clerk Ian Shugart in January 2021. The call urged public service leaders to take action to remove systemic racism from Canada’s institutions.

According to the 2022 Public Service Employee Survey results for the PCO, seven per cent of the 710 employees who responded said they had been the victim of on-the-job discrimination in the previous 12 months. Of the 35 respondents who identified as Black, 12 per cent said they had been the victim of discrimination. Ten per cent of the 145 racialized, non-Indigenous respondents indicated they had been the victim of discrimination, and five per cent of non-racialized, non-Indigenous employees did as well.

Of those who said they had been the victim of discrimination, 31 per cent said it had been targeted at their national or ethnic origin, followed by age-based discrimination at 30 per cent. Twenty-nine per cent said the discrimination they faced was based on their racial identity, 25 per cent said it was due to sexism, and 23 per cent said the discrimination was based on skin colour.

The vast majority of those employees who said they experienced discrimination—75 per cent—said the source had been a supervisor or manager, followed by 19 per cent who said it came from coworkers, 18 per cent who said employees from other departments, and three per cent who indicated they had been discriminated against by their subordinates.

Nearly half of the employees—47 per cent—who said they had been the victims of discrimination said they had taken no action in response due to fear of reprisals or expectations that doing so would be futile.

In an interview with The Hill Times following the Aug. 1 march, Black Class Action Secretariat CEO Nicholas Marcus Thompson questioned how the government can be trusted to implement any measures regarding the International Decade for People of African Descent, or even lead its own call to action to address anti-racism in the public service when the leadership responsible for doing so are themselves perpetrators.

During this year’s official Government of Canada Black History Month reception on Feb. 7 at the Canadian Museum of History, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau (Papineau, Que.) announced that Canada would extend its recognition of the decade until 2028, giving Canada the “full 10 years.” Trudeau’s government officially recognized the UN General Assembly 2015 proclamation of the decade in January 2018.

Since 2019, the federal government has announced several measures and investments attributed to Canada’s recognition of the decade, including $200-million over five years for the Supporting Black Canadian Communities Initiative, $265-million over four years to the Black Entrepreneurship Program (BEP), $200-million to establish the Black-led Philanthropic Endowment Fund, and the development of Canada’s Black Justice Strategy to address anti-Black racism and systemic discrimination in the criminal justice system. The strategy “aims to help ensure that Black people have access to equal treatment before and under the law in Canada.”

Thompson noted that the PCO’s response to the report did not include an acceptance of responsibility or an apology.

“No apology for the pain they’ve caused their employees … for the microaggressions or the use of the N-word,” Thompson said. “The first step should be an apology.”

In response to the coalition’s publication of the report, the PCO issued a similar statement to the one it sent to The Hill Times, highlighting the steps its senior management team has taken to “reinforce” its commitment to Shugart’s call to action, and pointing to the increases in representation within its workforce and executive since 2020.

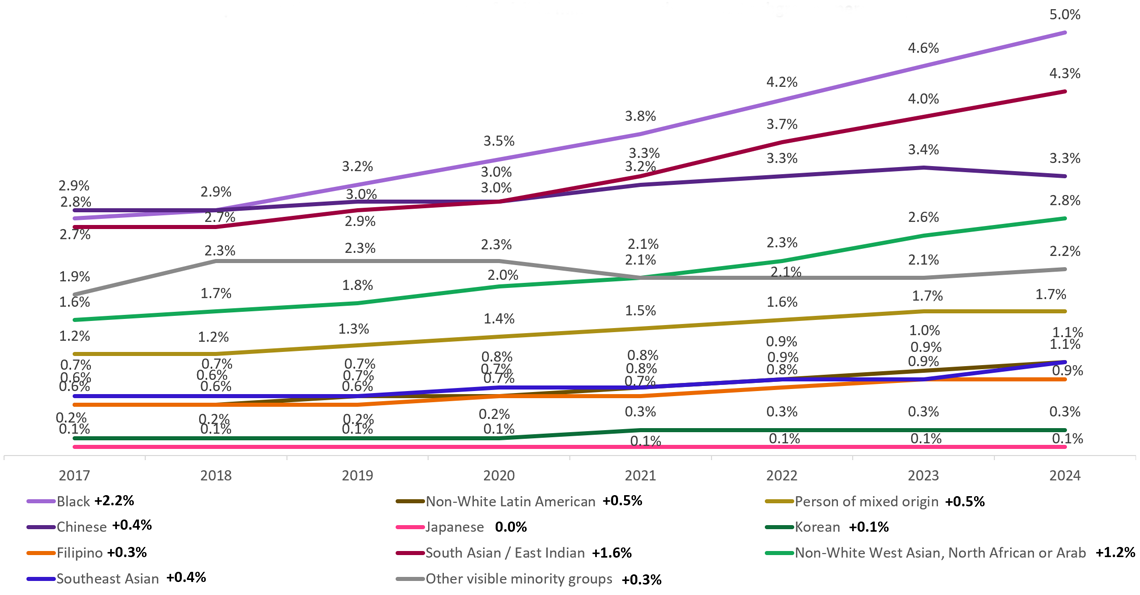

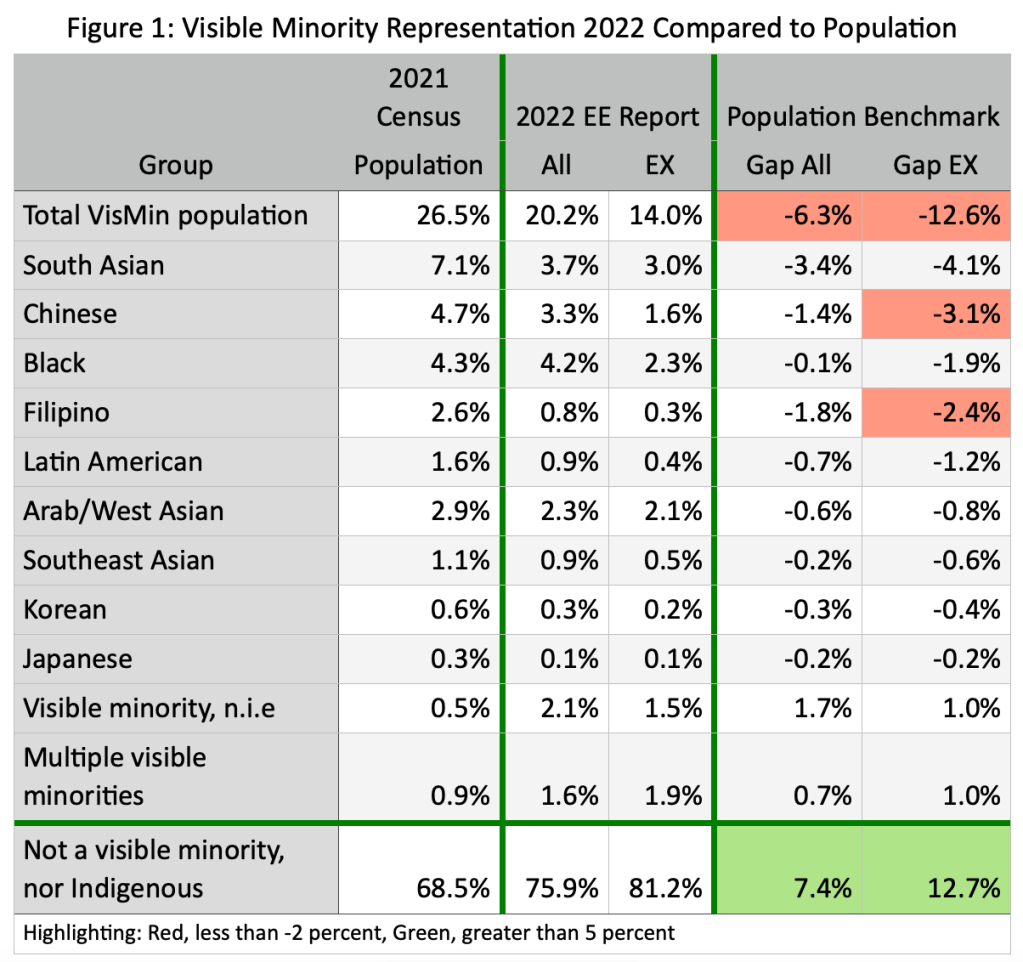

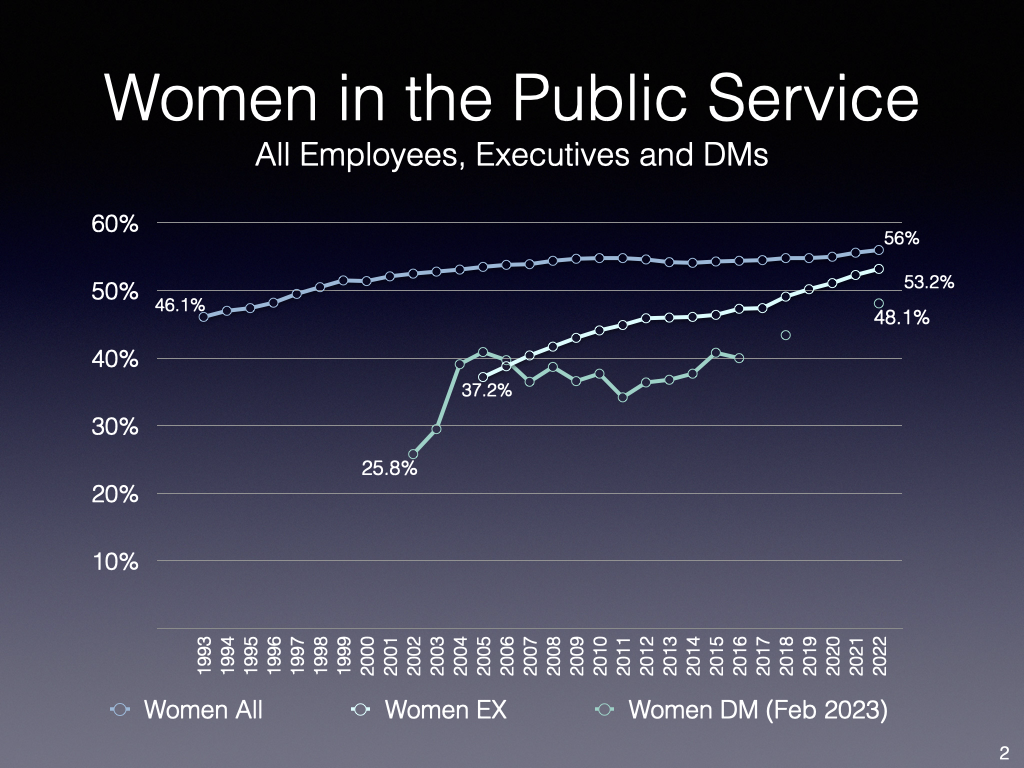

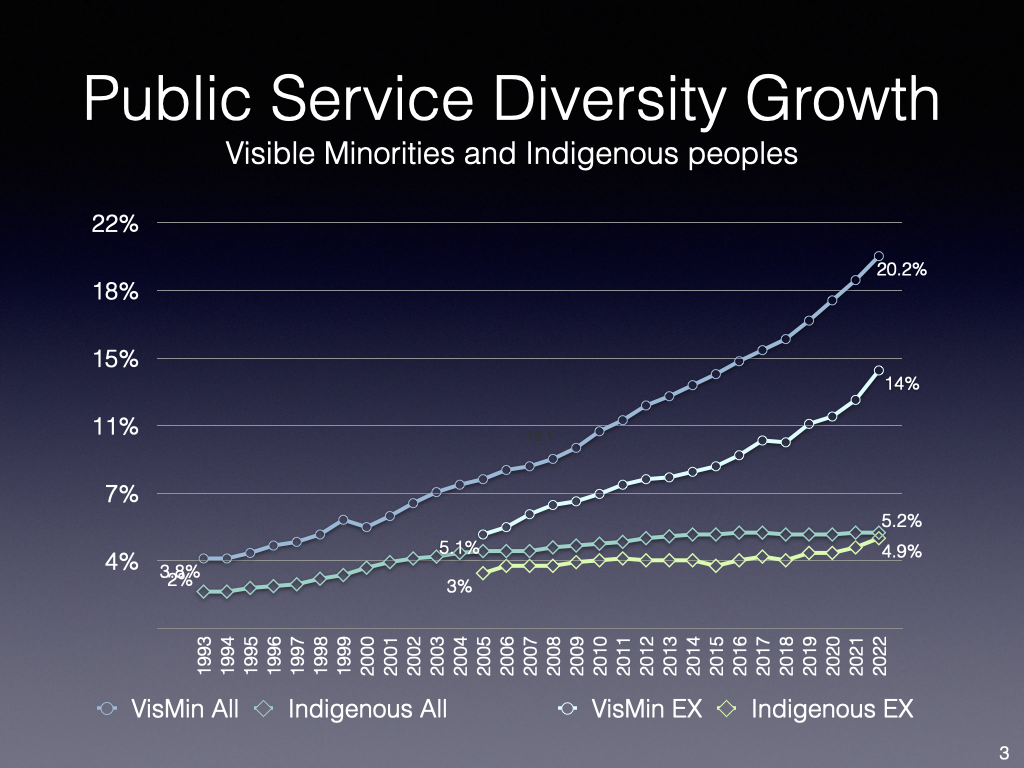

Between March 2020 and 2024, the PCO says that of its 1,200 employees, Black representation increased from 3.4 per cent (29 employees) to 5.8 per cent (66 employees). It also noted an increase from 2.7 per cent to 2.9 per cent for Indigenous employees, 16.5 per cent to 23.9 per cent for racialized employees, and an increase in women employees from 53.9 per cent to 57.8 per cent.

Within the executive, PCO says it has increased its representation in all those categories as well, but did not provide the underlying number of employees those percentages are based on, which Thompson said helps mask the reality of the situation.

“They rely on percentages when it suits them because they could say they had a 50 per cent increase, but that could just represent one more employee if they only had two before,” Thompson explained. “We want to see representation increase, but it must be done proportionately.”

As for the steps the PCO says it has taken in its response, Thompson said many of those were performative “events,” and lack the depth required to comprehensively tackle the systemic issues identified in Zellars’ report and Shugart’s call to action.

However, Thompson said the “trust has been broken,” and the coalition no longer believes the PCO can “fix itself.”

“If we want to see accountability, we need resignations,” Thompson said.

Alongside its reiteration of the long-standing calls for the creation of a Black Equity Commissioner and the settlement of the class-action lawsuit filed against the federal public service in December 2020, the coalition is also calling for the resignations of deputy clerk Natalie Drouin, who was responsible for the discrimination file since 2021, and Matthew Shea, assistant secretary to the cabinet, ministerial services and corporate affairs, and the head of PCO corporate services since 2017.

“The PCO can’t fix itself on this issue, so we need an arm’s-length commissioner to audit and direct it,” Thompson said, suggesting that one of the reasons so little action had been taken on Zellars’ report was because it had been “optional.”

Thompson also noted that while the government has created commissioners or special envoys to tackle issues of antisemitism, Islamophobia, or anti-LGBTQ2S+ hate, there is “no such thing” to address anti-Black discrimination.

“We’ve been needing specialized solutions to addressing anti-Black discrimination, recognizing that it’s unique from all other forms of racism and discrimination,” Thompson said, adding that the federal Anti-Racism Secretariat does not even have a mandate to investigate the public service.

“It’s an outward-facing secretariat,” Thompson said. “It has no mandate to investigate, audit, or examine any forms of discrimination in the public service.”

Thompson said that the Black Equity Commissioner would also need structural support, including the creation of a new Department of African Canadian Studies to function similarly to Crown–Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, and the changes to the Employment Equity Act suggested by the federal task force earlier this year.

Last December, the Employment Equity Act Review Task Force presented its findings to then-labour minister Seamus O’Regan (St. John’s South–Mount Pearl, Nfld.), recommending that Black and LGBTQ employees should be recognized as separate groups under the Employment Equity Act, instead of falling under the label of “visible minority.”

When it was implemented in 1986, the Employment Equity Act was intended to dismantle barriers to employment for minority communities. The four groups the act recognized as facing those barriers are women, Indigenous people, people living with disabilities, and visible minorities.

Speaking with reporters on Dec. 11, 2023, O’Regan said he was personally “delighted” by the recommendation, and the government has said it “broadly supports” it, according to reporting by CBC News.

In a statement to The Hill Times, the office of current Labour Minister Steve MacKinnon (Gatineau, Que.) said his predecessor’s initial commitments are only the “first steps” in the government’s work to transform Canada’s approach to employment equity.

“We look forward to tabling government legislation that is comprehensive of the needs of marginalized communities across Canada, and knocks down the barriers that prevent people from achieving their full potential in the workplace,” the statement reads.

Consultations on the Equity Act Review Task Force report will continue until Aug. 30.