Changing how U.S. forms ask about race and ethnicity is complicated. Here’s why

2023/04/28 Leave a comment

Good explainer. Canada’s visible minority categories provide much richer detail:

The first changes in more than a quarter-century to how the U.S. government can ask about your race and ethnicity may be coming to census forms and federal surveys.

And the Biden administration’s revival of this long-awaited review of federal standards on racial and ethnic data has resurfaced a thorny conversation about how to categorize people’s identities and the ever-shifting sociopolitical constructs that are race and ethnicity.

While this policy discussion is largely under the radar, the stakes of it touch the lives of every person in the United States.

Any changes to those standards by the White House’s Office of Management and Budget could affect the data used to redraw maps of voting districts and enforce civil rights protections, plus guide policymaking and research. They could also influence how state and local governments, as well as private institutions, generate statistics.

Here are a few things to know about this complicated effort that could change OMB’s Statistical Policy Directive No. 15:

Asking about race and ethnicity in a combined question could shrink a mysterious “Some other race” category

The current standards require federal forms that ask participants their identities to inquire about race and ethnicity through two separate questions. That’s why on census forms, for example, before you see the race question, there’s a question about Hispanic or Latino identity, which the U.S. government considers to be an ethnicity that can be of any race.

But for the 2020 census, close to 44% of Latinos either did not answer the race question at all or checked off only the box for the mysterious catchall category “Some other race,” according to data the Census Bureau released last month.

“They provide really important insights to what we’ve seen in our research over the decade — that Hispanics continued to find great difficulty with answering the separate questions on ethnicity and on race,” Nicholas Jones, director of race and ethnic research and outreach in the bureau’s Population Division, says about the data, the release of which the bureau moved up to help inform discussions about OMB’s standards.

The rise of “Some other race” — which is legally required on the census by Congress and is now the second-largest racial category in the U.S. after white — helped drive earlier research by the bureau into alternative ways of asking about race and ethnicity.

Combining those two topics into one question, while allowing people to check as many boxes as they want, is likely to reduce confusion and the share of Latinos who mark “Some other race,” bureau research from 2015 suggests.

And that has led an OMB working group to propose making a single combined question the new required way of collecting self-reported racial and ethnic data.

How would a combined question likely change how many people identify as Asian, Black or Pacific Islander?

The bureau’s research involved comparing how people could respond to a combined question vs. separate questions.

Its testing in 2015 – along with similar testing in 2010 and 2016 – found no statistically significant differences in the shares of participants who reported identifying as Asian, Black or Pacific Islander. (There are conflicting findings about the potential impact on the percentage of people reporting as American Indian or Alaska Native.)

But Howard Hogan, a former chief demographer at the bureau who retired from the agency in 2018, contends that research is inconclusive on the potential effects a combined question could have on those groups, particularly on the Black population.

“We don’t know for sure. It’s possible that it would have no effect or even increase. But it’s also equally possible, and I believe slightly more likely, that it would reduce,” Hogan says about a combined question’s impact on the share of people identifying as Black, adding that not all of the bureau’s experiments were designed to test how people may respond to a combined question when it’s asked by a census worker in person, which is how many people of color have participated in the count rather than filling out a form on their own.

The bureau was able to do a month of in-person interviewing for its testing in 2016, and it found no statistically meaningful differences in the shares of people identifying as Asian, Black or Pacific Islander.

Despite the limitations of the agency’s research, the bureau’s officials continue to stand behind their recommendation that a combined question would be the “optimal” way of asking about a person’s race and ethnicity.

“We’re confident in the sampling methodology as well as the consistent results that we’ve seen across three, large national tests,” says Sarah Konya, chief of the bureau’s census testing and implementation branch.

There are concerns about how a combined question could affect racial data about Latinos

Major civil rights organizations focused on census and data issues have also voiced their support for a combined question.

But a campaign called “Latino Is Not A Race,” which is led by a group of researchers who are part of the afrolatin@ forum, has raised concerns that a combined question would allow some Latinos to answer the question by only checking a box for “Hispanic or Latino.”

“The idea that there are some Latinos who are just Latino is contributing to the myth that Latinos are exempt from racialization. That’s not true. Our history has never been that. If you go back to any country in Latin America, you will see a racial hierarchy where whites were on top, brown-skinned people were somewhere in the middle, and Black people and people racialized as Indigenous have been on the bottom,” says Nancy López, a sociology professor who directs the University of New Mexico’s Institute for the Study of “Race” and Social Justice and is calling for research into an additional racial category that could be meaningful to Latinos who are racialized as “Brown.”

The OMB working group has said it’s looking into doing more testing of the combined question’s effects by this August, and outside advisers to the bureau on its Census Scientific Advisory Committee have recommended additional tests and focus groups on specifically how Latinos would respond to this race-ethnicity question format.

Any follow-up research is running up against a summer 2024 deadline that OMB has set for its review of the standards in order to enact changes before the end of President Biden’s first term and in time for them to be incorporated into 2030 census preparations, which are already underway.

In the meantime, both López and the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials Educational Fund are calling for the standards to clearly define the difference between the concepts of race and ethnicity, which the OMB working group acknowledges many people understand to be similar or the same.

If there’s no combined question, there may be no new “Middle Eastern or North African” checkbox

Entangled within the discussion about the combined-question proposal is the possibility of a new checkbox for “Middle Eastern or North African” — a category that the OMB working group has proposed to no longer classify as white under the federal standards.

Many people in the U.S. with origins in Lebanon, Iran, Egypt and other countries in the Middle East or North Africa do not identify as white people, and advocates for Arab Americans and other MENA groups have spent decades pushing for a checkbox of their own on the census and other forms.

Including a “Middle Eastern or North African” checkbox would likely reduce the share of participants who mark “White” or “Some other race,” while increasing the shares marking “Black” or “Hispanic or Latino,” the Census Bureau’s 2015 research suggests.

But if OMB does not change the standards to allow for a combined question about race and ethnicity, it’s not clear whether a new checkbox for “Middle Eastern or North African” would be approved. The bureau’s research has not specifically tested treating that category on forms as an ethnicity, which has long been the preference for the Arab American Institute and other advocates for a MENA category.

Source: Changing how U.S. forms ask about race and ethnicity is complicated. Here’s why

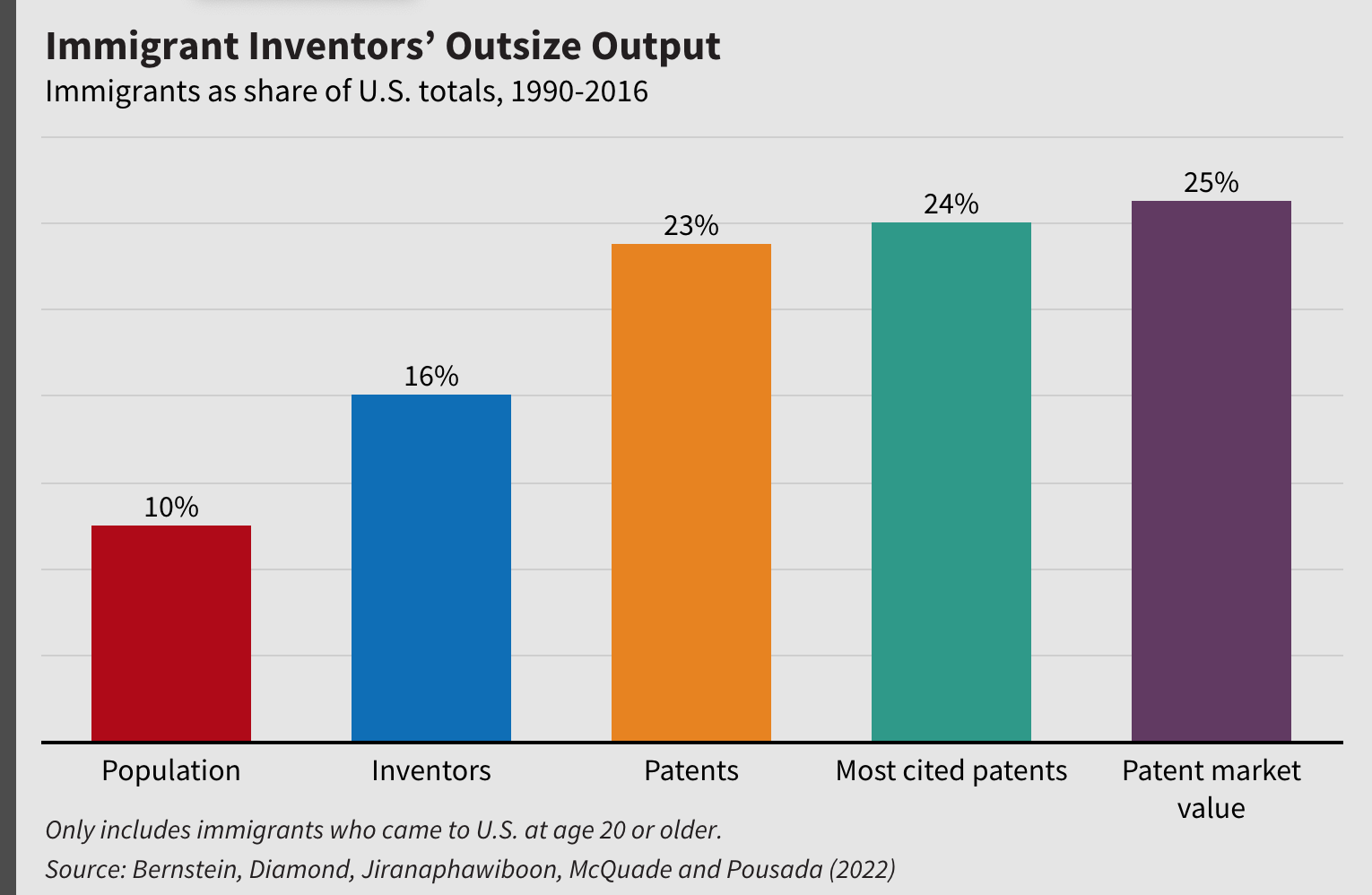

The immigrant innovation gap

The immigrant innovation gap