Theo Argitis: Canada’s great immigration experiment is ending

2025/06/20 Leave a comment

Good take:

For nearly the first time in our history, Canada’s population growth has come to a near standstill. Remarkably, the state of things is such that we are celebrating this as a policy success and long-overdue correction.

Statistics Canada released its quarterly population estimates, showing the country grew by 20,000 people in the first three months of this year. That’s the third weakest quarterly increase in data going back to 1946—and less than one-tenth the average quarterly gain over the past three years.

Four provinces and one territory—Newfoundland and Labrador, Quebec, Ontario, British Columbia, and Yukon—actually posted population declines.

The numbers reflect the dramatic reversal of policy late last year by the former Trudeau government, when it abruptly tightened permit approvals for international students and foreign workers after overseeing record immigration levels since 2021.

Under the plan, the intake of new permanent residents, or what the government calls immigrants, would be lowered from 485,000 in 2024 to 365,000 by 2027.

The number of non-permanent residents living in Canada—which had increased five-fold since 2015 to more than 3 million—would be cut by about one million over two years.

That post-pandemic rush of newcomers exacerbated housing shortages, strained public services, and disrupted the job market. It was perhaps the worst policy error of the past two decades, and in need of correction.

But, ironically, the sharp reversal in policy is now creating its own problems, impacting everything from demand for cell phones and banking services to funding for universities and colleges.

The whole episode has been a mass social experiment that will be studied for years.

“You’re going to see a ton of research on this, no question, because it’s like this little experiment here in Canada that no other country has done to this extent,’’ said Mikal Skuterud, a labour economist at the University of Waterloo and director of the Canadian Labour Economics Forum. “And there’s all kinds of dimensions to how this impacted the economy.”

The latest numbers suggest the government’s curbs are beginning to work. While still elevated, the number of non-permanent residents has started to decline—down almost 90,000 from its peak in September. The number of permanent residents, or immigrants, is now running at an annual pace closer to 400,000, down from nearly half a million.

Prime Minister Mark Carney has essentially adopted the Trudeau plan, which if successful will keep the current population steady at about the current 41.5 million level over the next two years. It would mark the first time since Confederation in 1867 that the country saw zero population growth.

Yet when viewed over the full horizon, the curbs will simply bring the average population growth rate for the decade back to about 1.3 percent, which is much closer to historical norms. We’re simply correcting a major policy anomaly.

Looking back, it’s too early to know for certain what effect the population surge had on wages and joblessness, according to Skuterud, who notes that younger Canadians, in particular, may have borne the brunt of it, given they tend to compete with newcomers for entry-level jobs.

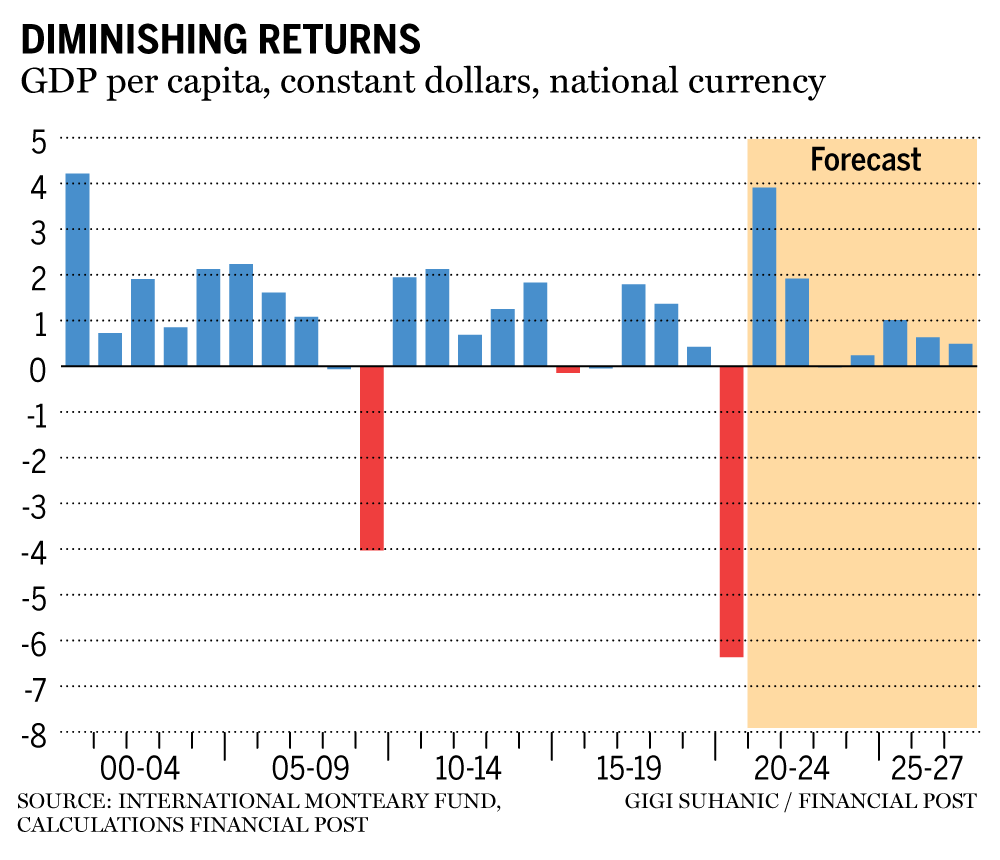

What’s less in dispute is how the immigration surge lowered average living standards.

The evidence suggests that looser entry requirements over recent years brought in lower quality workers. Because of this, the economy failed to grow in line with population. The size of the pie didn’t grow fast enough to keep up with the number of people trying to take a slice.

The end result was the erosion of public confidence in immigration, which could linger in Canadian politics for years.

This is particularly true among younger Canadians, who now appear more open to curbing immigration levels. For many, tighter labour markets and more affordable housing—not higher population numbers—are the priority. Slower immigration supports those goals.

So, how did the government misjudge the situation so badly? And is there a lesson here for the Carney government?

Part of the problem stemmed from the unique distortions of the pandemic. The government overestimated labour shortages and then overcompensated by opening the immigration floodgates.

But there was also a broader miscalculation. Trudeau emerged from the pandemic with renewed ambitions and a belief that he had an expanded mandate to pursue transformative change, including on the immigration front.

Ambition, however, has a way of outpacing reality. And overshooting is always a risk when leaders grow too confident in their ability to enact change.

Carney is now putting forward an ambitious agenda of his own. Whether he’ll draw any lessons from Canada’s great immigration experiment remains to be seen.

Source: Theo Argitis: Canada’s great immigration experiment is ending