Todd: This should be the first Canadian election that focuses on migration

2025/03/28 Leave a comment

I suspect, however, that it will not given that immigration, like so many other issues, is drowned out by the existential crisis of the Trump administration. But yes, appointments by PM Carney provide a hook to raise the issue and cite the excessive influence of the Century Initiative in past government policy before former immigration minister reversed course. As I have argued before, his changes provide space for immigration policy discussions without being labelled as xenophobic or racist.

Skuterud’s comments on rotating immigration ministers is valid and unfortunately former minister Miller was shuffled out by PM Carney:

A controversial appointment put migration in the headlines on the same weekend that Prime Minister Mark Carney announced a snap election.

The investment fund manager and former head of the Bank of Canada, who won the Liberal leadership contest two weeks ago, became the subject of news stories focusing on how he has chosen Mark Wiseman, an advocate for open borders, as a key adviser.

Wiseman is co-founder of the Century Initiative, a lobby group that aggressively advocates for Canada’s population to catapult to 100 million by 2100. Wiseman maintains Canada’s traditional method of “screening” people before allowing them into the country is “frankly, just a waste of time.” The immigration department’s checks, he says, are “just a bureaucracy.”

Wiseman believes migration policy should be left in the hands of business.

The appointment of Wiseman is an indication that Carney, a long-time champion of free trade in capital and labour, is gathering people around him who value exceptional migration levels and more foreign investment, including in housing.

Carney denied a charge by Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre that bringing in Wiseman “shows that Mark Carney supports the Liberal Century Initiative to nearly triple our population to 100 million people. … That is the radical Liberal agenda on immigration.”

Carney tried this week to distance himself from the Century Initiative, telling reporters Wiseman will not be advising him on migration.

For years, migration issues have been taboo in Canada, says SFU political scientist Sanjay Jeram.

But the Canadian “‘immigration consensus’ that more is always better” is weakening, Jeram says. Most people believe “public opinion toward immigration has soured due to concerns that rapid population growth contributed to the housing and inflation crises.” But Jeram also thinks Canadian attitudes reflect expanding global skepticism.

Whatever the motivations, Poilievre says he would reduce immigration by roughly half, to 250,000 new citizens each year, the level before the Liberals were elected in 2015. The Conservative leader maintains the record volume of newcomers during Trudeau’s 10 years in power has fuelled the country’s housing and rental crisis.

Carney has said he would scale back the volume of immigration and temporary residents to pre-pandemic levels, which would leave them still much higher than when the Conservatives were in office.

What are the actual trends? After the Liberal came to power, immigration levels doubled and guest workers and foreign students increased by five times. Almost three million non-permanent residents now make up 7.3 per cent of the population, up from 1.4 per cent in 2015.

Meanwhile, a Leger poll this month confirmed resistance is rising. Now 58 per cent of Canadians believe migration levels are “too high.” And even half of those who have been in the country for less than a decade feel the same way.

Vancouver real-estate analyst Steve Saretsky says Carney’s embracing of a key player in the Century Initiative is a startling signal, given that migration numbers have been instrumental in pricing young people out of housing.

Saretsky worries the tariff wars started by U.S. President Donald Trump are an emotional “distraction,” making Canadian voters temporarily forget the centrality of housing. He says he is concerned Canadians may get “fooled again” by Liberal promises to slow migration, however moderately.

Bank of Canada economists James Cabral and Walter Steingress recently showed that a one per cent increase in population raises median housing prices by an average of 2.2 per cent — and in some cases by as much as six to eight per cent.

In addition to Carney’s appointment of Wiseman, what are the other signs he leans to lofty migration levels?

One is Carney’s choice of chief of staff: former immigration minister Marco Mendicino, who often boasted of how he was “making it easier” for newcomers to come to the country. Many labour economists said Mendicino’s policies, which brought in more low-skilled workers, did not make sense.

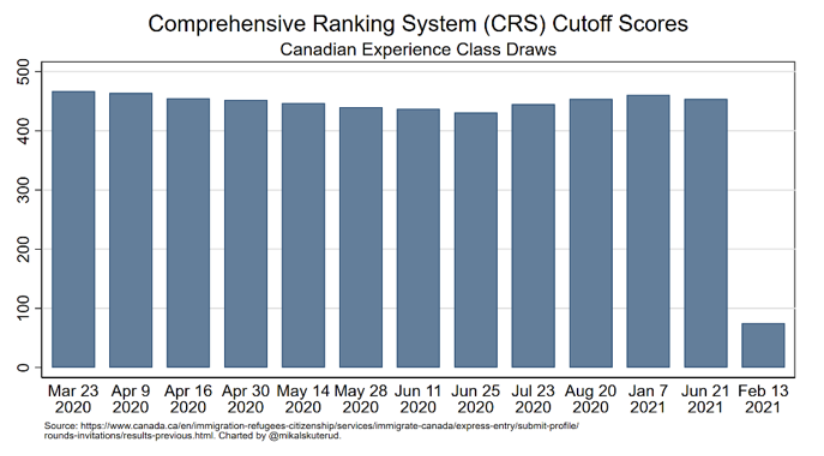

By 2023, the Liberals had a new immigration minister in Marc Miller, who began talking about reducing migration. But Carney dumped Miller out of his cabinet entirely, replacing him with backbench Montreal MP Rachel Bendayan. Prominent Waterloo University labour economist Mikal Skuterud finds it discouraging that Bendayan will be the sixth Liberal immigration minister in a decade.

New ministers, Skuterud said, are vulnerable to special interests, particularly from business.

“It’s a complicated portfolio,” Skuterud said this week. “You get captured by the private interests when you don’t really understand the system or the objectives. You’re just trying to play whack-a-mole, just trying to meet everybody’s needs.”

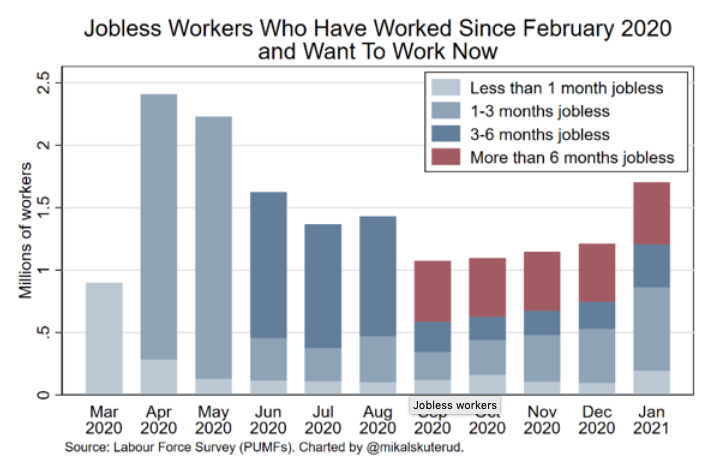

Skuterud is among the many economists who regret how record high levels of temporary workers have contributed to Canada being saddled with the weakest growth in GDP per capita among advanced economies.

Last week, high-profile Vancouver condo marketer Bob Rennie told an audience that he pitched Carney on a proposal to stimulate rental housing by offering a preferred rate from the Canada Mortgage Housing Corp to offshore investors.

We also learned this week that Carney invited former Vancouver Mayor Gregor Robertson to run as a Liberal candidate. Robertson was mayor during the time that offshore capital, mostly from China, flooded into Vancouver’s housing market. When SFU researcher Andy Yan brought evidence of it to the public’s attention, Robertson said his study had “racist tones.” Two years later, however, Robertson admitted foreign capital had hit “like a ton of bricks.”

It’s notable that Carney, as head of the Bank of England until 2020, was one of the highest-profile campaigners against Brexit, the movement to leave the European Union.

Regardless of its long-lasting implications, Brexit was significantly fuelled by Britons who wanted to protect housing prices by better controlling migration levels, which were being elevated by the EU’s Schengen system, which allows the free movement of people within 29 participating countries.

For perhaps the first time, migration will be a bubbling issue this Canadian election.

While the link to housing prices gets much of the notice, SFU’s Jeram also believes “the negative framing of immigration in the U.S. and Europe likely activated latent concerns among Canadians. It made parties aware that immigration politics may no longer be received by the public as taboo.”

Source: This should be the first Canadian election that focuses on migration