Les débats sur la laïcité ont permis au Canada de marquer des points dans la guerre d’usure avec le Québec pour la loyauté des immigrants racisés. Le sentiment d’appartenir à la communauté québécoise n’a pas décliné entre 2012 et 2019, mais cet « élan » s’est néanmoins affaibli par rapport à la volonté d’être canadien, indique une nouvelle étude.

Ce déficit d’appartenance à la province s’est aussi étendu aux minorités non religieuses et à celles qui sont francophones durant cette période. Elles étaient pourtant moins susceptibles d’être touchées par les deux « événements focalisateurs » sous la loupe de cet article publié récemment dans la Revue canadienne de science politique que sont le projet de charte des valeurs et le projet de loi 21 sur la laïcité de l’État.

Les chercheurs ont mesuré l’évolution de l’appartenance à travers trois enquêtes qui coïncident dans le temps avec ces grands débats de société, soit en 2012, 2014 et 2019. « Au début de la période étudiée, on voit que, chez les immigrants non religieux ou francophones, il n’y a pas de préférence marquée entre le Québec ou le Canada. L’appartenance à l’un ou l’autre est aussi forte », explique Antoine Bilodeau, professeur de science politique à l’Université Concordia et coauteur de l’étude avec Luc Turgeon.

Ces perceptions évoluent, avec un creux en 2014, pour ensuite stagner envers le Québec. Mais pendant ce temps, le sentiment d’appartenance envers le Canada grandit, et cet effet est généralisé à tous les immigrants racisés, pas seulement ceux qui sont religieux ou qui ne sont pas francophones.

« Cela indique que les groupes minoritaires ont perçu ces débats comme une remise en question plus large de la relation avec la majorité. Ce qui est en trame de fond de tout ça, chez certains partisans [de la laïcité], mais beaucoup chez ses détracteurs, c’est que ces politiques reflètent le malaise du Québec avec la diversité grandissante », détaille-t-il.

Mais ce lien n’est pas causal avec une certitude absolue. Les chercheurs constatent plutôt que l’aiguille a bougé en faveur du fédéral sur le cadran de l’appartenance et attribuent cette modification à des facteurs déjà bien démontrés. Même si la transformation n’est pas totale, elle correspond dans le temps avec ces moments clés et elle est cohérente avec la littérature scientifique.

Un certain nombre d’études au Québec laissaient déjà entendre que les débats sur les symboles religieux avaient nourri un sentiment d’exclusion, mais elles ne permettaient pas de faire cette comparaison avant et après les propositions législatives.

Les deux auteurs, cette fois, ne peuvent « que conclure que les débats sur l’interdiction des symboles religieux à travers les propositions législatives qui ont pris place en 2014 et en 2019 ont contribué à détériorer la relation des immigrants racisés avec la communauté politique québécoise ou, plus précisément, ont contribué à creuser l’écart dans le sentiment d’appartenance à l’avantage du Canada », écrivent-ils dans l’étude.

Deux modèles

« Au fond, la perception est que le modèle fédéral est plus flexible dans sa définition de qui il reconnaît comme citoyen à part entière », résume le professeur, qui étudie ces aspects depuis nombre d’années. Et les débats sur la laïcité sont « venus consolider ou accentuer cette perception ».

Les deux coauteurs citent d’ailleurs l’ancien premier ministre Jacques Parizeau, qui s’inquiétait en 2013 que le projet de charte des valeurs du Parti québécois fasse la part belle au fédéralisme, qui allait pouvoir ainsi se présenter comme le véritable défenseur des minorités.

« Il [Jacques Parizeau] disait “vous allez perdre de vue la dynamique de compétition”. L’étude lui donne raison », explique M. Bilodeau.

Encore plus frappant aux yeux du coauteur de l’étude, la perte du sentiment d’appartenance vis-à-vis du gouvernement québécois « est causée par ses propres actions », plutôt que, par exemple, la passivité ou l’incapacité à rattraper le fédéral.

Autre fait intéressant, le sentiment d’appartenance des immigrants racisés a été mesuré par deux aspects : l’attachement et le sentiment d’être accepté. Le concept d’appartenance est ainsi mieux compris dans sa dimension relationnelle, une relation à deux sens.

« C’est un peu comme demander “est-ce que je veux faire partie du groupe ? [attachement] Puis, est-ce que j’ai la perception que le groupe veut que j’en fasse partie ? [sentiment d’acceptation]” », détaille M. Bilodeau.

On pourrait penser que c’est surtout le sentiment d’acceptation qui a été touché : « Intuitivement, on dirait, ce geste me montre qu’ils ne veulent pas de moi. » Mais il y a, selon le professeur, un effet boomerang sur le désir de faire partie de la communauté, sur le sentiment d’attachement. « Non seulement c’est que je sens, qu’ils ne veulent pas [que j’appartienne au groupe], mais ça me fait remettre en question ma propre volonté d’être Québécois par rapport à “je veux être Canadien”. »

Des expériences vécues

« J’aimerais beaucoup me tourner vers le sentiment d’appartenance envers le Québec, mais on nous fait sentir qu’on n’y appartient pas. Alors, il faut se tourner ailleurs », explique d’ailleurs en entrevue Jana, une jeune musulmane. Le Devoir a choisi de ne pas publier son nom de famille, car la Montréalaise est encore mineure.

Pour elle, ce sont assurément les débats sur la laïcité qui ont entamé son sentiment d’appartenance : « Avant, je m’identifiais comme Québécoise, mais, avec les nouvelles lois, j’ai senti que ça a créé deux classes différentes : ceux qui peuvent réaliser leurs rêves et les autres, qui ne le peuvent pas. »

« Moi, je voulais devenir avocate pour défendre l’équité sociale, mais j’ai l’impression que je ne peux pas choisir cette carrière sans sacrifier ma religion », dit la jeune femme, qui porte le hidjab.

La Loi sur la laïcité de l’État, connue d’abord comme projet de loi 21, interdit le port de signes religieux chez les agents qui incarnent l’autorité de l’État, y compris les juges et les procureurs de la Couronne.

Jana pourrait exercer à titre d’avocate en pratique privée, reconnaît-elle, mais elle a l’impression que certaines portes lui sont déjà fermées avant même qu’elle entame des études de droit.

Pour Garine Papazian-Zohrabian, professeure de psychopédagogie à l’Université de Montréal et psychologue clinicienne, cette étude va dans le même sens que ce que d’autres travaux ont démontré : « les approches coercitives freinent le sentiment d’appartenance », a-t-elle déjà écrit sur plusieurs tribunes.

« Je vois aujourd’hui les conséquences de la loi 21 [Loi sur la laïcité de l’État] dans le milieu enseignant », dit Mme Papazian-Zohrabian. Elle voit avec grande déception les embauches de personnel non légalement qualifié dans les écoles, « alors qu’on prive nos élèves de bonnes enseignantes » parce qu’elles portent le voile.

« On pousse les gens à se recroqueviller sur eux-mêmes et à trouver une place uniquement dans leur communauté. Symboliquement, on ne peut plus parler d’intégration », dit-elle.

Mme Papazian-Zohrabian a émigré du Liban et elle est d’origine arménienne, « petite-fille de rescapés d’un génocide », donc à même de comprendre l’importance de l’identité, remarque-t-elle.

Les politiques et le discours sur l’immigration ont créé « une dynamique de plus en plus polarisée », selon la spécialiste. Beaucoup d’immigrants ont pourtant « choisi le Québec ou le Canada parce que c’est une société progressiste et une société de droit. Quand ils se sentent attaqués ici, ça crée de la détresse chez eux ».

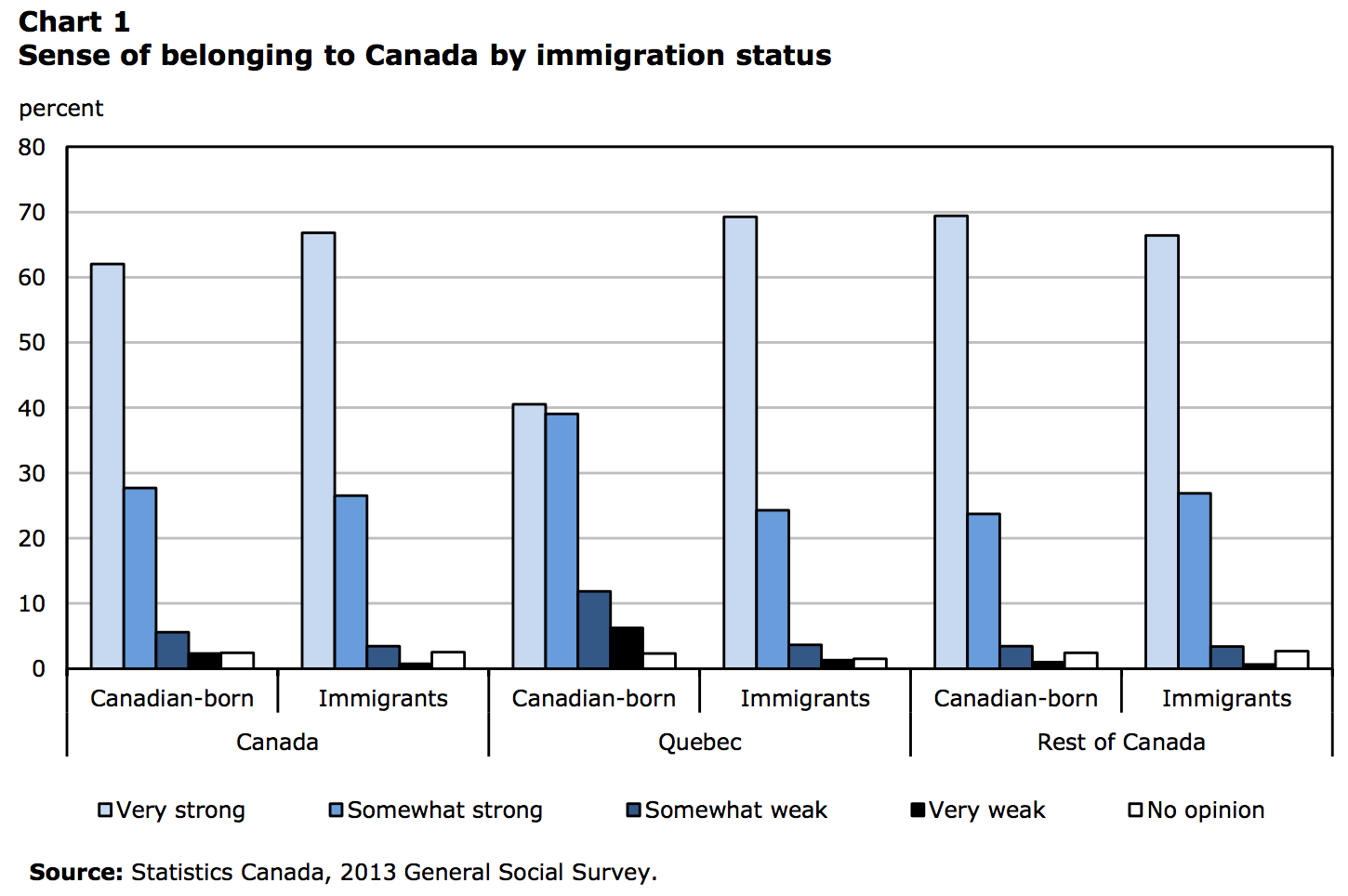

Important study by Statistics Canada and John Berry from the General Social Survey confirming high levels of belonging to Canada:

Important study by Statistics Canada and John Berry from the General Social Survey confirming high levels of belonging to Canada: