Canada is getting bigger. Are we setting the country and its newest citizens up for success?

2023/07/03 Leave a comment

Good overview of some of the issues:

Debbie Douglas was 10 when she came from Grenada to join her parents in Canada.

On her first day of school in 1973, her family had to fight with the principal, who wanted to put her back a year and have her take ESL because she spoke English with a Grenadian accent. In the end, she was allowed to attend Grade 5.

“But by the end of the first week on the playground, I got called the N-word, and it shook me to my core,” Douglas recalls. “And I looked around to see if anybody had heard and nobody said anything … In a school of 500, there were three Black kids and I don’t recall any other kids of colour.”

Despite a degree in economics from York University, her stepfather could only find a job as a financial planner. Her mother, a teacher back home, ended up working in a nursing home.

But if you were to ask Douglas’s mother what her migration experience has been, Douglas says, she would say Canada has been very good to her family.

“My parents worked hard. We went to school. We now have a middle-class life. It’s a great migration story,” Douglas, executive director of the Ontario Council of Agencies Serving Immigrants, told a forum about Canada’s immigration narrative this past May.

“Great” has never meant “easy” for newcomers arriving in this country. Douglas says the stories of immigrants’ struggles and sacrifice were just often not heard.

Yet Canada has long maintained its status as a destination to which newcomers aspire. The immigration story that’s told has, for decades, been one of perceived success — both from the perspective of those forging new lives here, and from the viewpoint of a country eager to grow.

Today, that national narrative appears to be under new strains that are threatening the social contract between Canada and its newcomers.

Canada’s population has just passed the 40-million mark, and it’s growing thanks to immigration.

Immigration accounts for almost 100 per cent of the country’s labour-force growth and is projected to account for our entire population growth by 2032.

Governments and employers from coast to coast have been clamouring for more immigrants to fill jobs, expand the economy and revitalize an aging population. The more, the merrier, it seemed, even during economic recession of recent years.

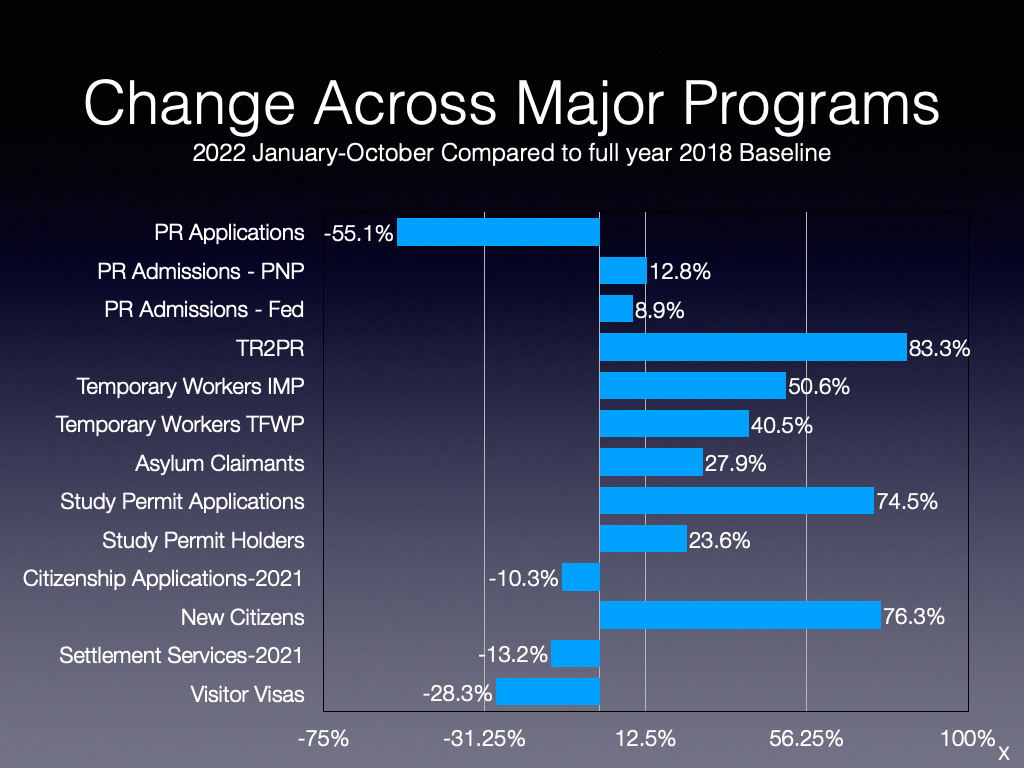

Post-pandemic, Ottawa is set to bring in 465,000 new permanent residents this year, 485,000 in 2024 and 500,000 in 2025 to boost Canada’s economic recovery after COVID.

Amid this push, there have been critiques that immigrants are too often being reduced to numbers — to units meant to balance the equations of our economy. While it is clear our economy needs immigration, what is it that newcomers need of Canada to ensure they can settle and thrive here? Are those needs being met?

Meanwhile, the federal government’s plan to bring in a historic level of immigrants has been met with some reservations domestically, as Canadians struggle with stubbornly high inflation amid global economic uncertainty resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and volatile geopolitics.

There is a sense of scarcity emerging in Canada, despite the country’s seemingly great wealth — whether it manifests in the housing crisis, a strained health-care system, or in the lack of salary increases that keep up to inflation.

While a national dialogue about Canada’s immigration strategy is overdue, some fear anti-immigrant or xenophobic backlash amid news, op-eds and social-media conversation that ties immigration to the strains already being felt.

One poll by Leger and the Association of Canadian Studies last November found almost half of the 1,537 respondents said they believe the current immigration plan would let in too many immigrants. Three out of four were concerned the levels would strain housing, health and social services.

“Canada is at a crossroads in terms of being able to continue to be a leader in immigration. It’s at a crossroads in its ability to provide the Canadian dream to those who move to the country,” says University of Western Ontario political sociologist Howard Ramos.

“It’s at a crossroads in terms of the infrastructure that’s needed to support this population, and it’s at a crossroads potentially at having widespread support for immigration.”

How Canada got to 40 million

Canada’s immigration strategy has long been about nation-building to meet both the demographic and economic aspirations of the country.

In 1967, Canada introduced the “points system,” based on criteria such as education achievements and work experience, to select economic immigrants. It was one of a series of measures that have gradually moved the immigration system away from a past draped in racism and discrimination.

The point system shifted a system that favoured European immigrants and instead helped open the door to those from the Global South for permanent residence in this country. The 2021 Census found the share of recent immigrants from Europe continued to decline, falling from 61.6 per cent to just 10 per cent over the past five decades.

Ottawa had turned the immigration tap on and off depending on the economic conditions, reducing intake during recession, until the late 1980s, when then prime minister Brian Mulroney decided to not only maintain but to increase Canada’s immigration level amid high inflation, high interest rates and high unemployment.

“There are real people behind those numbers — people with real stories, real hopes and dreams, people who have chosen Canada as their new home,” Mulroney’s immigration minister, Barbara McDougall, said back in 1990 of a five-year plan to welcome more than 1.2 million immigrants.

The plan, too, was met with what today sound like familiar criticisms of the country’s ability to absorb the influx of people.

“We don’t think the federal government is taking its own financial responsibility seriously. The federal government is cutting back. They’re capping programs,” Bob Rae, then Ontario’s NDP premier, commented.

“They’re not transferring dollars to match the real cost, whether it’s training, whether it’s (teaching) English as a second language, whether it’s social services.”

Another big shift under Mulroney’s government was the focus on drafting well-heeled economic and skilled immigrants to Canada, which saw the ratio of permanent residents in family and refugee classes drop significantly from about 65 per cent in the mid-1980s to about 43 per cent in 1990s, and about 40 per cent now.

Mulroney’s measures severed Canada’s immigration intake from the boom-and-bust cycle of the economy. Successive governments have stuck to the same high-immigrant intake, regardless of how good or bad the economy was performing.

It has set Canada apart from other western countries, where immigration issues are often politicized. Coupled with the official multiculturalism policy introduced by the government of Pierre Trudeau in 1971 in response to Quebec’s growing nationalist movement, it has contributed to Canada’s image as a welcoming country to immigrants.

Public support for immigration has remained fairly high and Canada seemed to have fared well despite such economic challenges as the burst of the dot-com bubble from the late 1990s to mid-2000s, the global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009, and the economic downturn driven by the oil-price slump in the mid-2010s.

Observers, however, note the challenges and circumstances of those economic fluctuations were different than what we see today: there was enough housing stock in the 1990s and the impacts of the crashes in the financial, tech and oil markets since were sectoral, regional and temporary.

Canada’s infrastructure problem

Except in Quebec, which has full control over its newcomer targets and selection, immigration is a federal jurisdiction in Canada, planned in silo from other levels of governments that actually deliver health, education, transportation and other services. Yet the impacts of immigration are felt locally in schools, transits and hospitals.

A lack of infrastructure investments and the rapid immigration growth have finally caught up with the country’s growth. “We spent decades not s upporting our communities,” says Douglas.

“We were not paying attention to building infrastructure. We were all under-resourcing things like community development and community amenities. We haven’t built adequate affordable housing.

“It’s now become a perfect storm. We have all these people and not enough of what is needed for everybody.”

While the majority of newcomers have historically settled in the big cities such as Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal, a growing number are moving to smaller cities and towns that in some cases are not ready for the influx. The share of recent immigrants settling in the Big Three dropped from 62.5 per cent in 2011 to 53.4 per cent in 2021, with second-tier cities such as Ottawa-Gatineau, Kitchener-Cambridge-Waterloo, London and Halifax seeing significant growth.

“I don’t think it occurred to them that they need to build infrastructure to be able to welcome people in. It’s a lack of planning. It is a lack of funding,” Douglas says.

“We’ve raised these immigration numbers without paying attention to what it means, what it is that we didn’t have. We are already facing a crisis and we are bringing in more people without addressing the crisis.”

Canadian employers are champions for more economic immigrants. Half of employers surveyed told the Business Council of Canada they were in favour of raising the annual immigration targets — provided there are greater investments in the domestic workforce, as well as in child care, housing and public transportation.

Goldy Hyder, the council’s president and CEO, says many of the day-to-day challenges Canadians and immigrants face are in fact driven largely by labour shortages, whether it’s in health care, housing, or restaurants and retail.

Around the world, he says, countries build infrastructure to spur population — and economic — growth, but in Canada, he contends, it’s been vice-versa.

Hyder sees this moment as a crucial one for raising immigration targets and maintaining public support. “We are at a seminal moment in the life of this country, because we’re at a seminal moment in the life of the world right now,” he says.

Hyder says the country’s immigration policy shouldn’t be just about bringing in people, it should be part of a bigger workforce and industrial strategy to ensure skills of all Canadians and immigrants are fully utilized in the economy in order to maintain the public support for immigration.

“We need to plan better. We need to be more strategic in that plan. And we need to work together to do that: federal, provincial, municipal governments, regulatory bodies, professional bodies, business groups,” he says.

“Let’s address the anxieties that Canadians are facing. You don’t sweep them aside or under a rug. We must have honest discourse with Canadians, fact-based about what we’re trying to do to make their lives better.”

The tradeoffs that come with population growth

The case made for increased immigration is often an economic one. That said, research has generally found the economic benefits of immigration are close to neutral. That’s because when it comes to population growth, there are always tradeoffs.

While bringing in a large number of immigrants can spur population growth and drive demand for goods and services, it will also push up prices even as the government is trying to rein in out-of-control costs of living, warn some economists.

When more workers are available, employers don’t have to compete and can offer lower wages. Further, just adding more people without investing into social and physical infrastructure such as housing and health care is going to strain the society’s resources and be counterproductive, economists say.

“For housing and health care, it takes a long time to catch up with the increased demand,” says Casey Warman, a professor in economics at Dalhousie University in Halifax, whose own family doctor is retiring. (He is now on a wait list seeking a new one, with 130,000 ahead of him.)

One of the main metrics of economic success has traditionally been a country’s overall GDP. Immigration and population growth can fuel the pool of labour and consumers and boost the overall GDP.

But there’s an emerging chorus of economists arguing that there is a better reflection of the standard of living and economic health in a country. That’s GDP per capita — productivity per person. The growth of Canada’s GDP per capita has been quite flat over the recent years, growing marginally from $50,750.48 in 2015 to $52,127.87 last year. Despite the recovery and high inflation amid the pandemic, it’s still below the $52,262.70 recorded in 2018.

Uncertainty about rapidly changing economic conditions, as well as the fast pace of technological adjustments, have also created uncertainty about what skills and labour will be in demand as the country moves forward.

“One big unknown now is how automation and especially AI is going to change the landscape for labour demand in the next five, 10 years … Is it going to decrease demand for labour?” Warman asks.

How to adapt in the face of this uncertainty, and how immigration should be approached in light of it, is a conversation Canada needs to have, experts say.

Ivey Business School economics Prof. Mike Moffatt says that who Canada is bringing in matters as much as immigration levels, and what’s happening with the economy is nuanced.

Economic, family and humanitarian classes are the three main streams of permanent residents coming to Canada, and each group has different impacts on the economy, generally with those who come as skilled immigrants having the highest earnings and weathering economic downturns best.

The profiles of the incoming immigrants and their ability to integrate into the economy matter, says Moffatt. Bringing in foreign-trained doctors and nurses who can’t get licensed from stringent regulators, for example, won’t help address the health-care crisis.

Still, Moffatt says his critique of Canada’s immigration plan is less about the ambitious targeted numbers than the pace of the increases, as well as the short notice for provinces and cities in planning for the influx.

“Whether it be on education, immigration support programs, labour market programs, all of these things, there’s no time to adjust,” says Moffatt, senior director of policy and innovation at the Smart Prosperity Institute, a think tank with a stated goal of advancing solutions for a stronger, cleaner economy.

“I do think we can have robust increases in the targets. I don’t think that’s necessarily a problem, but let the provinces and cities know what you’re doing.

“There’s no collaboration. There’s no co-ordination. They are not working with the provinces and municipalities and the higher-education sector in order to come up with any kind of long-term thinking. It’s very short-term in nature.”

Should Canada cap international students and migrant workers?

Aside from questions about the immigration plan Canada has, there are also questions about the plan it doesn’t have.

The national immigration plan sets targets for the number of permanent residents accepted yearly, but leaves the door wide open for temporary residents.

That has become a bigger issue over the years as Canada has increasingly shifted to a two-step system to select skilled immigrants who have studied and worked in Canada, bringing in more international students and temporary foreign workers than permanent residents.

According to Statistics Canada, there were close to a million (924,850) temporary residents in Canada in 2021, making up 2.5 per cent of the population.

The majority of them, including asylum-seekers, can legally work here; the remaining 8.7 per cent who don’t have work permits includes visitors such as parents and grandparents with the so-called super visa, who can stay for up to five years.

Temporary residents, who don’t have credit history for loans and mortgages in Canada, are more likely to be renters and public transit users (but eligible for some provincial health care), says Anne Michèle Meggs, who was the Quebec Immigration Ministry’s director of planning and accountability before her 2019 retirement.

“In the past, it wasn’t an issue, because we had a relatively small temporary migrant population, so we managed, even though we took the approach that we just bring them in and we don’t look after what happened to them afterwards,” says Meggs, whose book “Immigration to Quebec: How Can We Do Better” was recently published.

“That’s fine. That population wasn’t out of control. So that’s why we still successfully managed and it didn’t become a crisis.”

However, under tremendous pressure from post-secondary institutions to recruit international students, and from employers to quickly bring in foreign workers, she said the balance has tipped. To not set targets for temporary immigration is to get into trouble, Meggs warns.

“We want people to come and we want people to stay. You want things to be good for everybody, including immigrants and including children. And I think the objective has to be to make sure that everyone gets treated with dignity,” she says.

“Immigrants are not just sources of labour or sources of financing of institutions or spending money to increase our national GDP. These are people. We have to get back to talking about the immigrants and not just immigration.”

Canada ‘cannot afford to allow for polarization’

Canada immigration overall has been a success in terms of forging positive public attitudes toward immigration and the political participation by immigrants, says Andrew Griffith, a retired director general of the federal immigration department.

He feels Canada now has the maturity to have an honest and informed conversation about immigration without the fear of being labelled as racist and xenophobic. The focus of the discussion, he says, should be on Canada’s capacity to ensure a good quality of life for those who are already here and those who will be coming.

“It’s not about keeping the immigrants out. It’s more that if we’re going to do this, we have to do it right,” says Griffith. “We have to make sure we have the right infrastructure, the right housing policies and everything like that.”

Any immigration plan, Griffith says, should go beyond the intake levels but study the potential socio-economic impacts and include inputs from provincial and municipal governments.

Canada has grown to become a country of 40 million, and it has not always been smooth sailing.

But Canadians have worked hard to make immigration work for everyone and the success has come down to how the growth has been managed and how the public support for immigration has been maintained.

“We cannot afford to allow for polarization, populism and xenophobia to kick in here because it’s a very slippery slope,” says Hyder, whose family arrived in Calgary from India in 1974 when he was seven. “Other countries have seen it. It can go downhill very fast.

“Immigration is part of the arteries of our soul. It is who we are as a people.”

Source: Canada is getting bigger. Are we setting the country and its newest citizens up for success?