Good article based upon the opinion piece by Dr. Barrett shared yesterday:

Should Canada deny care to ”birth tourists,” pregnant women who visit Canada with the sole purpose of delivering their babies here, thereby obtaining automatic Canadian citizenship for their newborns?

It’s a provocative, and, some say, dangerous suggestion. However, a leading expert in preterm and multiple births is arguing that Canadian hospitals and doctors should have “absolutely zero tolerance” for birth tourism, a phenomenon that is rising once again now that COVID travel restrictions have been dropped.

It’s a “sorry state of affairs” that women in Canada face wait times of 18 months or longer for treatment for pelvic pain, uncontrolled bleeding and other women’s health issues, Dr. Jon Barrett, professor and chief of the department of obstetrics and gynaecology at McMaster University wrote in an editorial in the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada.

“The thought that even ONE patient seeking birth tourism would potentially take either an obstetrical spot out of our allocated hospital quota, or even worse, a spot on the gynaecologic waiting list, should be enough to unite all in a position that anything that in any way facilitates this practice should be frowned upon,” Barrett wrote.

“These are non-Canadians getting access to health care, which we haven’t got enough of for our own Canadians,” he said in an interview.

When planned low-risk births go wrong, and babies end up spending weeks in intensive care, hospitals can be left with hundreds of thousands in unpaid bills. One Calgary study found that almost $700,000 was owed to Alberta Health Services over the 16-month study period.

The women themselves are also at risk, Barrett said, of being “fleeced” by unscrupulous brokers and agencies charging hefty sums upfront for birth tourism packages that include help arranging tourist visas, flights, “maternity” or “baby hotels” and pre-and post-partum care.

And, while he declined to provide specific examples, “Tempted by large sums of money, even the best of us can be tempted into poor practice,” Barrett wrote.

The issue has triggered high emotions and debate among Canada’s baby doctors. Under Canada’s rule of jus soli, Latin for “right of soil,” citizenship is automatically conferred to those born on Canadian soil.

Birthright citizenship gives the child access to a Canadian education and health care. They can also sponsor their parents to immigrate when they turn 18.

Other developed nations require at least one parent to be a citizen, or permanent resident.

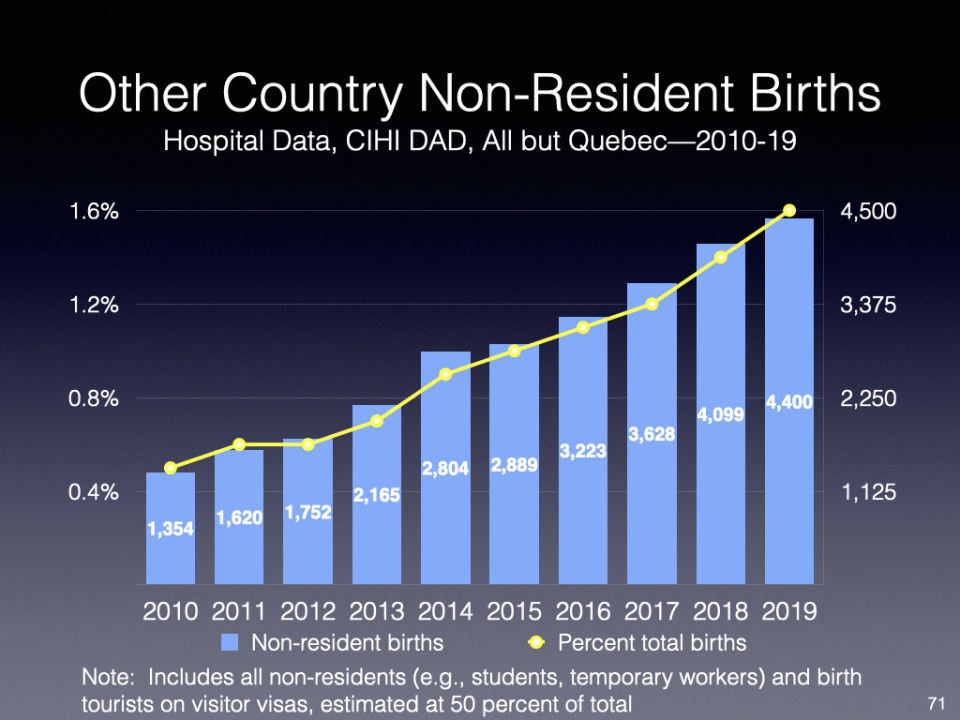

According to data collected by Andrew Griffith, a former senior federal bureaucrat in Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, “tourism” births account for about one per cent, give or take a bit, of total births in Canada. Data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information show Canada hosted 4,400 foreign births in 2019.

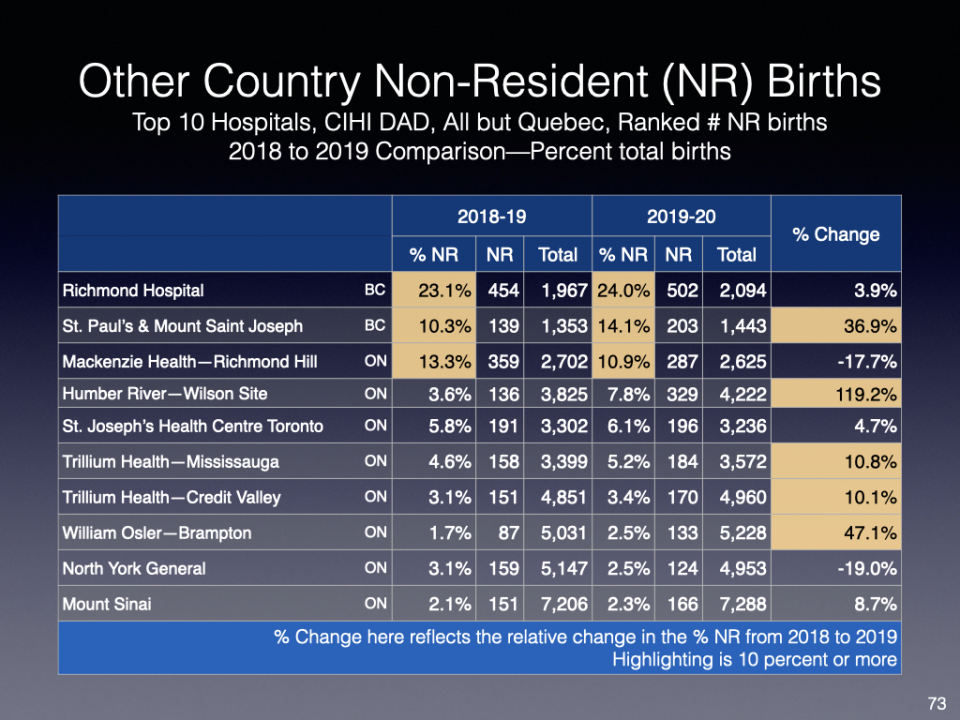

At a national level, the numbers aren’t huge, however they can become significant at the local level, Griffith said: In pre-COVID years, non-resident births accounted for up to 25 per cent of all births at a single hospital in Richmond, B.C., while the numbers at a handful of other popular destination hospitals in Ontario and Quebec approached five to 10 per cent of all births.

“In a system that is tight and stretched, it does become an issue at the hospital level,” Griffith said.

But birth tourism also undermines the integrity and confidence in Canada’s citizenship process, he said, “It appears like a short cut, a loophole that people are abusing in order to obtain longer-term benefit for their offspring.”

“It sends the wrong message that basically we’re not very serious in terms of how we consider citizenship and its meaningfulness and its importance to Canada,” Griffith said.

Barrett is careful to stress that birth tourism absolutely doesn’t apply to women who happen to be in Canada because of work, or study programs, or as refugees. “We must declare that people who are here for a genuine reason should have seamless access to health care,” he said.

What he opposes are the “non-urgent planned and deliberate birth tourists in our hospitals.”

Doctors can’t deny care to a woman in labour. Emergency care would always be given, he said. “Obviously you’re never going to turn somebody away.”

But doctors and hospitals could decline to provide pregnancy care before birth. “Eventually, if you create this unfriendly environment,” Barrett said, “if everybody said we are not looking after you and not facilitating this, eventually people will not come. They would realize they are not getting what they are seeking, which is optimal care.”

Some women step off the plane 37 weeks pregnant, three weeks from their due date. “That’s why my colleagues say, ‘You can’t do that. People are going to suffer,’” Barrett said. “Yes, unfortunately, people are going to suffer, because they won’t get pregnancy care, and they’ll show up at the hospital without antenatal care.”

While some women do come to Canada seeking superior medical care, “let’s be frank,” said Calgary obstetrician and gynecologist Dr. Colin Birch. “The principal motivator is jus soli.

“Sometimes its veiled under, ‘I want to get better medical care,’ but, interestingly, they fly over several countries that can give them the equivalent care to Canada to get here,” said Birch, countries that don’t offer jus soli.

Birch is co-author of the Calgary study, the first in-depth look at birth tourism in Canada. Their retrospective analysis, a look back over the data, involved 102 women who gave birth in Calgary between July 2019 and November 2020. A deposit of $15,000 was collected from each birth tourist, and held in trust by a central “triage” office to cover the cost of doctors’ fees. A deposit wasn’t collected to cover fees for hospital stays for the mom or baby; women were made aware they would be billed directly.

The average age of the woman was 32. Most came to Canada with a visitor visa, arriving, on average, 87 days before their due date. Birth tourists were most commonly from Nigeria, followed by the Middle East, China, India and Mexico. Overall, 77 per cent stated that the reason for coming to Canada was to give birth to a “Canadian baby.”

Almost a third of the women had a pre-existing medical condition. One woman needed to be admitted to the ICU after delivery for cardiac reasons, another was admitted for a high blood pressure disorder and stroke. Nine babies required a stay in the neonatal intensive care unit, including one set of twins that stayed several months. Some women skip their bills without paying.

“Every conversation about heath care is that we haven’t got money for health care,” Birch said. “Yet you’ve got unpaid bills of three-quarters of a million. It’s not chump change.”

But denying care is a dangerous and unrealistic “gut reaction” that some hospitals have already taken, Birch wrote in his counter editorial for the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. “Let’s be very clear: They won’t let them through the front door, or they send them on to another hospital.”

“You cannot have zero tolerance for patients,” Birch said. “You can’t do that because that leads to maternal and fetal complications.”

The federal government could tweak the rule of “jus soli,” excluding people who just come to Canada on a temporary visitor visa to give birth, and then leave, he and others said. “You do the Australian approach, that one of the parents has to be a citizen of the country,” said Griffith, a fellow of the Environics Institute and Canadian Global Affairs Institute.

Three years ago, the United States announced it would start denying visitor visas to pregnant foreign nationals if officials believe the sole purpose was to gain American citizenship for their babies.

While some have said birth tourists are being demonized as “queue jumpers and citizenship fraudsters,” Griffith isn’t convinced birth tourism is a politically divisive issue.

“I don’t think there are very many people that really would get upset if the government sort of said, ‘We’re going to crack down on birth tourists, women who come here specifically to give birth to a child and who have no connection to Canada.’”