Developments have been coming so fast that this column risks going obsolete before it can be published. But as of this time, early Friday morning, Canada has largely discontinued its military operations in Afghanistan. The bulk of our forces withdrew the day before, leaving only a few soldiers and staff to co-ordinate with our allies on the ground. There were two bomb attacks near the airfield Thursday that killed at least a dozen American military personnel, injured 15 others, and killed dozens of local Afghans; the exact number is hard to come by, but reports Friday put it at over 100.

As the mission ends on this bitter note, it’s important for us to separate the reasonable criticisms of our federal government’s response from the unreasonable.

Partisan opponents of the Liberals, sensing opportunity, have been levelling some wildly unfair accusations of Liberal responsibility. Partisan Liberals for their part, are attacking strawmen erected for the purpose of deflecting all criticism, fair or otherwise.

We have to cut through the fanatics on both sides and be very clear about this: the evacuation was always going to be messy. We were never going to get everyone out. But it is obvious that we did not get out as many people as we should have. It’s clear that we made major errors, including failing to work with veterans and aid groups on the ground; we did not lift bureaucratic hurdles quickly enough. We lost time dithering. That is our shameful failure.

It is not the Canadian government’s fault that our American allies decided to pull out of the conflict. Frankly, I still can’t entirely blame either the Trump or Biden administrations for that decision, although the execution of that decision has been catastrophic.

This was not a decision made in Ottawa, but in Washington, and for entirely American reasons. Further, the Liberals are not to blame for the U.S. government’s massive intelligence failure. We were caught totally flatfooted by the rapid and total collapse of the former Afghan government — what had been expected to take months took days. Canada, a member of both NATO and the Five Eyes, relies heavily on the intelligence gathered by our larger, more powerful ally. I do not fault Liberal party leader Justin Trudeau or his government for being caught unprepared.

So let’s dispense with that nonsense right away. In the big picture, there is not a whole hell of a lot Canadian governments could have done to avoid this crisis.

But we could’ve managed the crisis much better.

Over the last 10 days, we’ve had repeated reports of bottlenecks caused by over-restrictive paperwork requirements. We’ve seen other allies flying helicopters into Kabul to allow them to retrieve their people from sites around the city; Canada has helicopters and the ability to deploy them (see photo above), but we didn’t follow suit.

Reports indicate that there was a gap of several days in any meaningful Canadian Armed Forces presence on the ground — and that gap set us back in terms of intelligence and planning. Canadian officials reportedly worried about the number of seatbelts on our transport planes even as other allies were loading their aircraft up with as many people as they could (we eventually began cramming evacuees into ours, as well). In several recent pieces here at The Line, Kevin Newman has described the struggle faced by those those trying to escape — people to whom we had had promised safe haven as their lives were now in peril due time they spent helping us during our missions in Afghanistan. There are numerous reports of our government telling these people to show up at gas stations and hotels — only to ghost them.

Facts beyond our control limited how effective we were ever going to be at getting people out, but we did not max out our effectiveness within those constraints. As a result, people will die who did not have to. The gap between the best-possible Canadian response and the actual Canadian response is a gap measured in lives.

Lauren Dobson-Hughes wrote about this in her piece in The Line yesterday: the Canadian government is bad at managing crisis. “Our foreign policy and development work has suffered from a lack of long-term, strategic planning and coherence,” she wrote. “Canada tends to hyper-focus on the minute details at the tactical level (no, the text on a roundtable invite does not need to be reviewed by an assistant deputy minister), but has much less ability to anticipate broader trends and challenges.”

Read her piece in full, if you haven’t — it’s worth your time. But it strikes me as perhaps simpler to say that the Canadian federal government cannot transition to an emergency mindset. Our leaders can stab the big red button until their fingers bleed — but nothing happens.

I’m not honestly sure if the problem is isolated pockets of bureaucratic dysfunction within a workforce that is mostly energized, nimble and effective, or the reverse: a generally sluggish series of inefficient institutions that smother to death the rare pockets of success that may accidentally spring to life within the hostile environment of our federal government. It would be good to know this, but in the end, it doesn’t really matter: whether we failed by a little or failed by a lot is of entirely academic interest to the people who’ll face Taliban bullets because of said failure. There are moments in life where you can’t grade on a spectrum of success, when it is a binary choice between success and failure. We failed thousands of our friends in Afghanistan, and for them, that failure is total.

Our armed forces seem to have responded to the challenge with their usual courage and professionalism. But of course they did — these are the people who live in a world where a split-second decision can mean the difference between survival and death. We train them for that kind of crisis management, and that training, combined with their understanding of the harsh nature of reality, allows them to work wonders despite chronic underfunding.

However, for most Canadian officials, products as they are of a rich, peaceful country far from danger — “a boat in safe harbour,” as Dobson-Hughes aptly described it — there’s one way of doing things: the usual way. And if the usual way means only letting people onto the plane if their paperwork is perfect, and even then, only until the limit set by how many seatbelts are aboard the plane, that’s what they’re going to do.

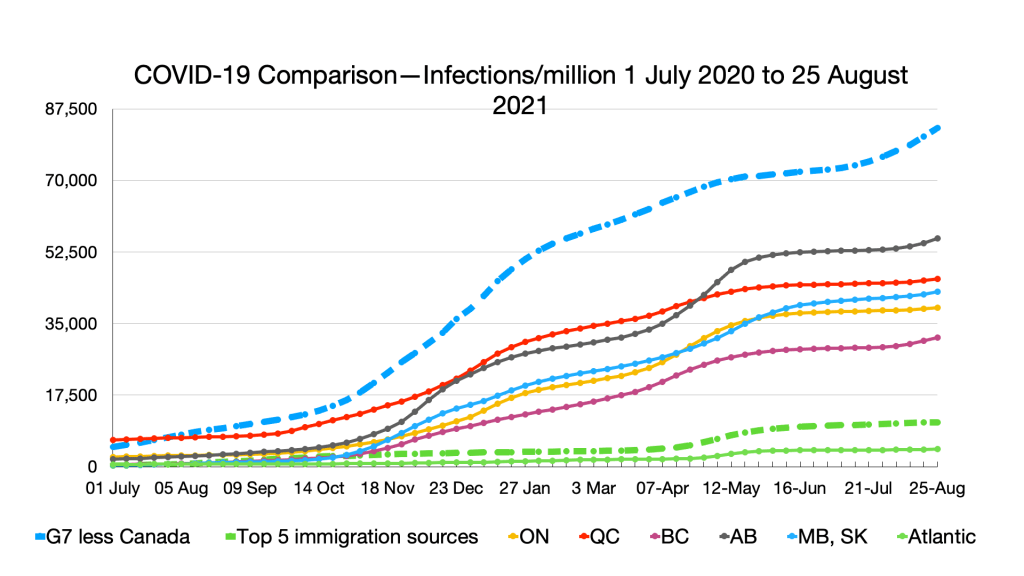

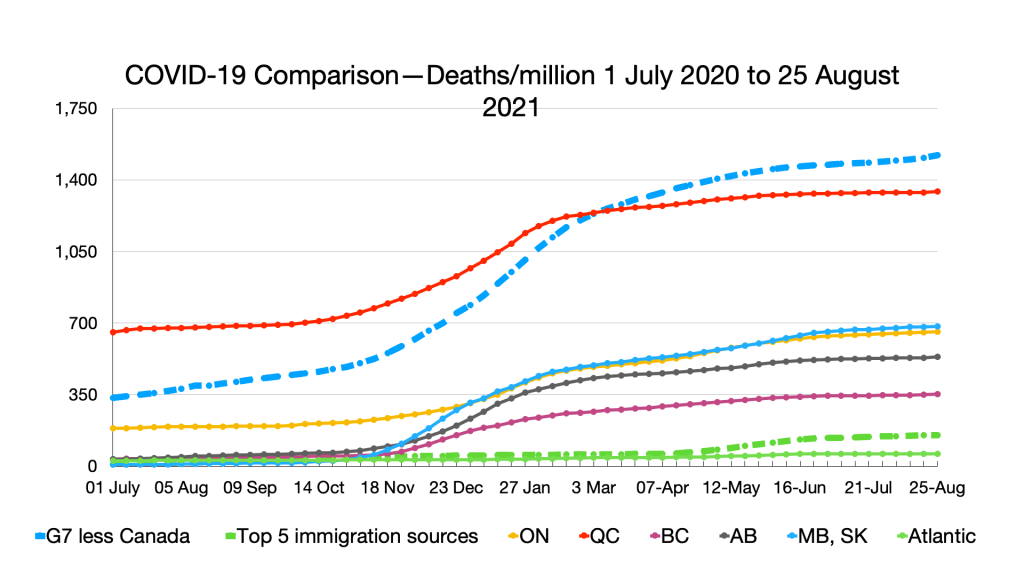

We saw this play out during the early phase of the pandemic, when even as countries all over the world where falling into the grips of raging, deadly outbreaks, the official line in Ottawa remained, essentially, “Sa’ll good!” The government was insisting that “the risk to Canada is low” weeks after most of us began loading up on toilet paper and canned soup. There was something in our government, as an institution, that prevented it from seeing what was coming, accepting it for what it was, and then shifting itself into high gear.

And when it finally came, we watched absurd moments; of federal officials insisting all was being appropriately managed at the airports, even as Canadians actually in the airports — myself included — were shouting that that wasn’t true. Provincial and local leaders finally sent their own people in to compensate for the federal government’s obvious inability not just to respond to the emergency, but really, to even comprehend it.

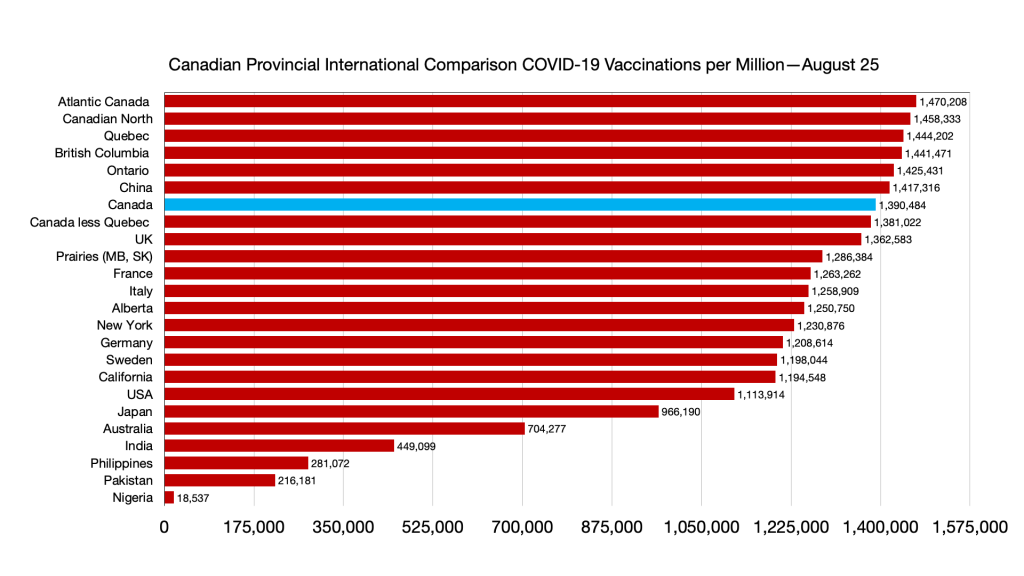

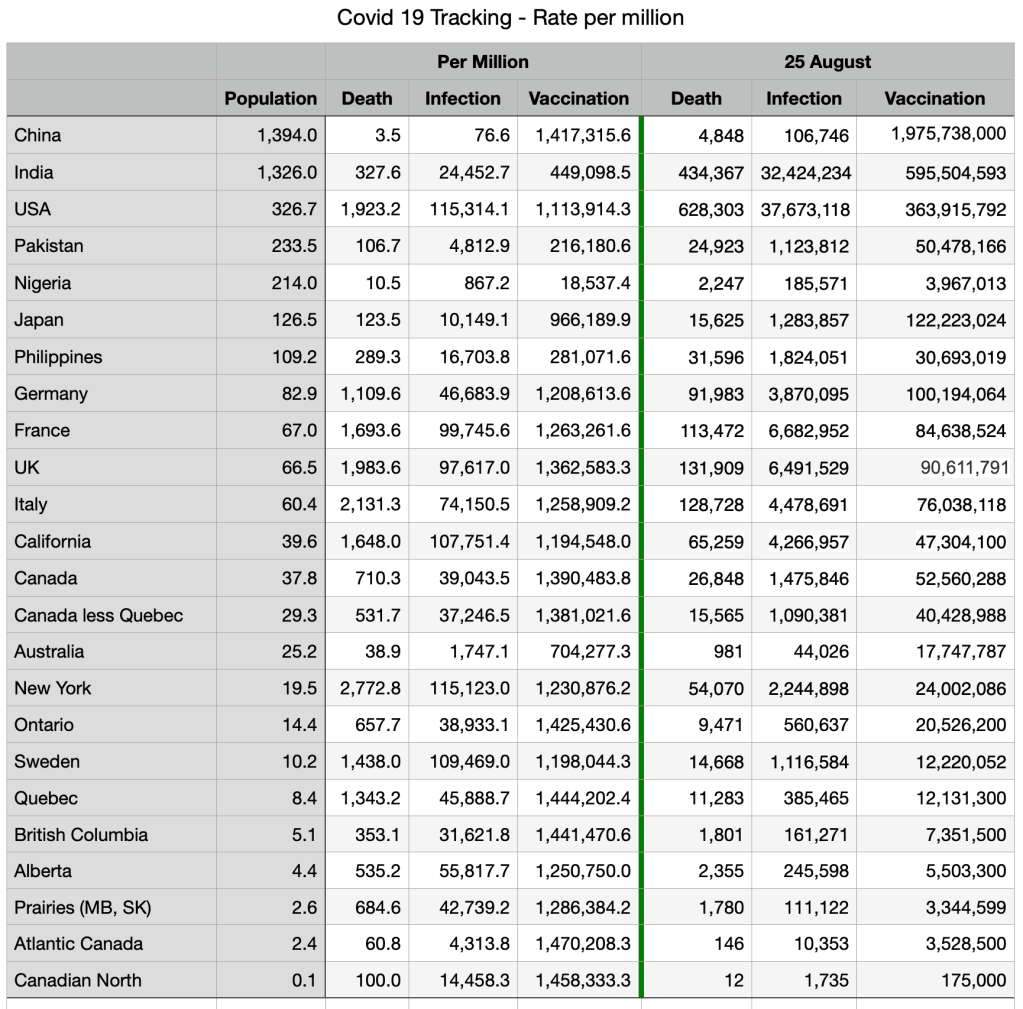

The government did eventually shift into crisis mode, and Ottawa did have some successes, including a vaccine procurement that beat expectations and fiscal support programs that were rushed into service with admirable speed. Andrew Potter, a contributor here, wrote wisely in the National Post early this year that governments specialize, and if there’s anything the federal government knows how to do, it’s send people money. It’s not that we can’t get anything right; millions of Canadians benefit from capably delivered government services (federal, provincial and local) every day. The failure is in our ability to respond quickly to the unexpected. Adapting on the fly requires a degree of flexibility that we simply do not have.

Some of this can be fixed with time and energy and money — I’ve been writing about the need for a larger, more capable Canadian military for years, and a few more C-17s certainly would have come in handy this week (alas, they’re no longer being built). Indeed, one of the side stories that didn’t get enough attention this week is a perfect example of how our institutional lethargy has real consequences on the ground: Canada has five C-17 transport aircraft, and the C-17 is designed to be refuelled in mid-flight by an aerial tanker. But Canadian evacuation efforts in Kabul faced fuel constraints because while our planes are capable in midair refuelling, our crews are not trained for it. Canada does have refuelling tanker aircraft, but our tankers aren’t compatible with our C-17s, and we haven’t trained our C-17 pilots to refuel from allied (mainly American) tankers. Canada is working to replace its current tanker aircraft, but until we pick a next-generation fighter — something we’ve been working on for literally decades, with successive governments refusing to close a deal due to the high cost of the program — we don’t know which type of refuelling system we’ll need. So this critical capacity remains absent from our military.

Of course, even the best-trained and equipped military cannot help us until we develop the ability to skip the shock and denial phase that seems to mark our automatic response to any crisis, and ram emergency action through a resisting bureaucracy. The ongoing election campaign no doubt hindered our response to the crisis in Kabul, but we shouldn’t overestimate by how much. COVID-19 caught us with our pants down and we had literally months of warning that that was likely to reach our shores.

Trudeau and the Liberals didn’t bring down Afghanistan or screw up the intelligence estimates. But they are the ones at the wheel of a government that has, yet again, failed to respond in real-time to a fast-moving crisis. Tens of thousands of Canadians died of COVID, and thousands of our friends abroad may now die at the hands of the Taliban. Some of those deaths were probably unavoidable, but not all of them. We could have saved more people here and in Kabul. That we didn’t is something we should be deeply ashamed of, and determined to never let happen again.