‘Fortress Australia’: Why calls to open up borders are meeting resistance

2021/05/28 Leave a comment

Of note and the challenge of reopening:

Australia has been one of the world’s Covid success stories, where infection rates are near zero and life mostly goes on as normal.

That’s in large part thanks to the early move to shut its borders – a policy that has consistently been supported by the public.

But after a year in the cocoon, there is growing unease in the country over the so-called “Fortress Australia” policy.

Recent announcements declaring that Australia won’t open up until mid-2022 – meaning a two year-plus isolation – have amplified concerns.

Critics argue the extension of closed borders will cause long-lasting damage to the economy, young people and separated families. It also tarnishes Australia’s character as open and free, they say.

Calls for a clear plan to pull Australia back into the world are growing, as the country wrestles with an uncomfortable tension – balancing the safety of closed borders against what is lost by living in isolation.

“A Fortress Australia with the drawbridge pulled up indefinitely is not where we want to be,” says former Race Discrimination Commissioner Dr Tim Soutphommasane.

“Australia is at its best when it’s open and confident – not fearful and insular.”

Locking the gate

In March 2020, the government closed the borders. It barred most foreigners from entering the country and put caps on total arrivals to combat Covid. Mandatory 14-day quarantine and snap lockdowns have also been used to control the virus spread.

The measures are extreme, and among the strictest in the world.

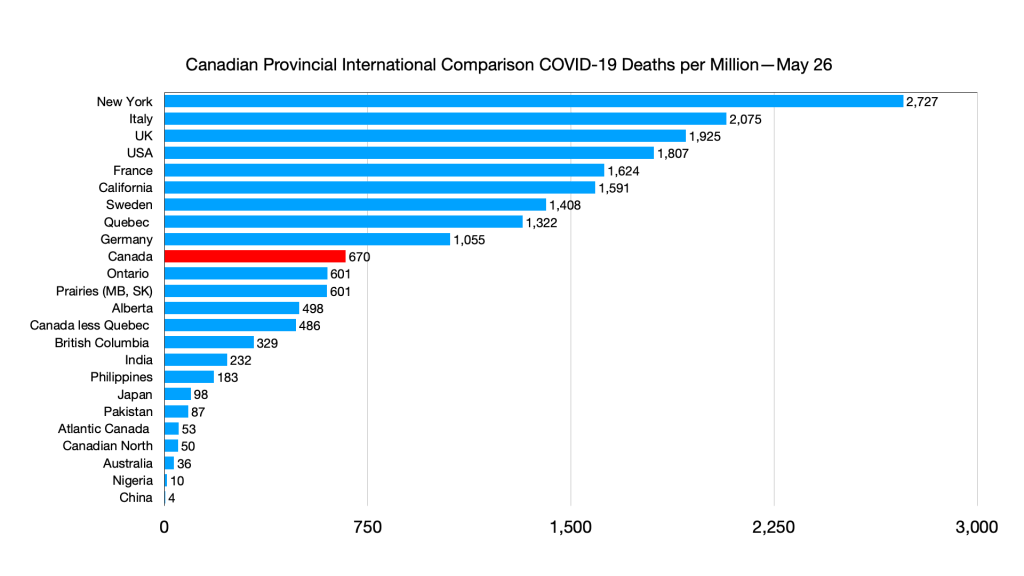

But they’ve worked. Australia regularly sees months without a single case in the community, and it has recorded fewer than 1,000 deaths in the pandemic.

Given that, the strict border controls have proven tremendously popular. Public polls regularly report 75-80% approval ratings for keeping the door shut.

Even higher numbers – around 90% – approve overall of the government’s pandemic handling, and trust in government has increased in contrast to views of voters in some Covid-ravaged nations.

Languishing behind

But the government now also faces mounting pressure over how it plans to handle the next phase of the pandemic.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison – who faces an election next year – has announced Australia won’t re-open borders until mid-2022. The exact timing and just how that will happen are unclear.

But the budget announcement was a shock extension to previous forecasts of an opening-up to occur slowly at the end of this year.

The main reason for the delay is vaccination.

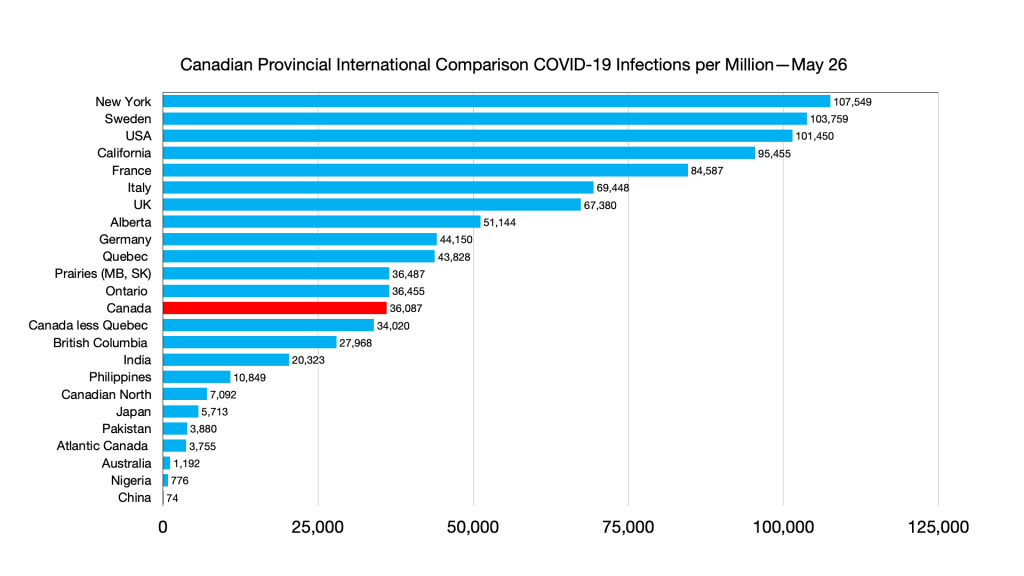

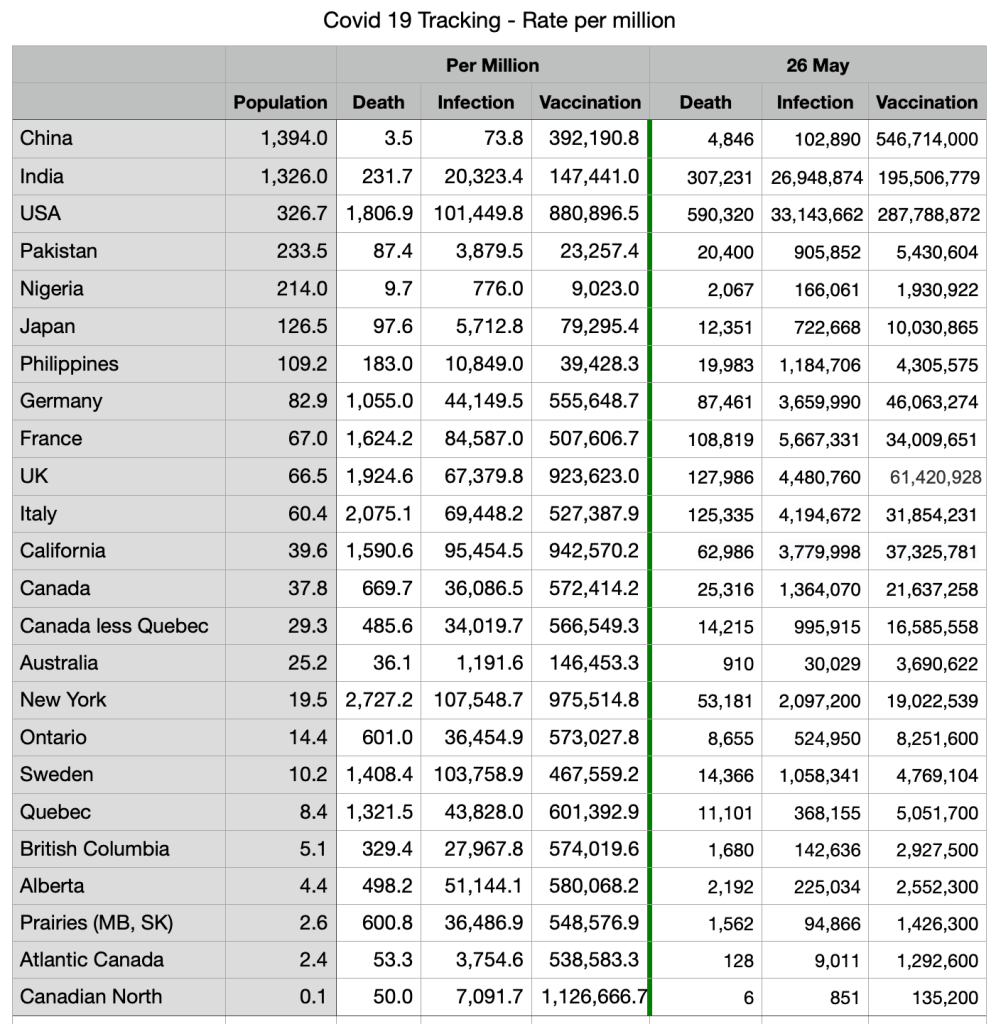

Australia’s immunisation programme has been beset with delays, and lags well behind other developed nations such as the UK and US.

Critics say complacency over the low virus circulation delayed its kick-off. And now rising hesitancy – fuelled at least in part by Australia’s isolation – has also slowed the vaccine rollout.

Facing those failures, the government fell back on the border ban as a resort, critics say.

That’s dealing a heavy blow to sectors like tourism and higher education. Australia’s strong migration programme – relied on to address skills shortages and population growth – has also been cut almost completely.

Ernst and Young, an accounting firm, estimates that Australia’s economy is losing A$7.6bn (£4.18; $5.9bn) a month from the closed borders.

So a group of experts from the University of Sydney have called for an exit plan to be put in place. People need to know their options and prepare for the future, they say.

Their “roadmap to re-opening” focuses on prioritising vaccination, expanding quarantine and starting trials to bring in people for affected industries.

They point to successful examples like the New Zealand travel bubble, and the Australian Open tennis tournament.

“The price of staying closed indefinitely is simply too great,” they wrote in a recent report.

“This is the case when measured in hard dollar terms, but also when measured against less tangible factors such as fuelling a negative and inwards-focused national psyche that threatens our global standing, as well as national unity and cohesion.”

‘Us and them’ mentality

Others have also voiced their concerns over how an extended retreat from the world could damage Australia’s character.

When Australia was parochial it had a White Australia policy (1900s-1970s), which restricted immigration from non-European nations. Multiculturalism has replaced that policy in recent decades, but the ideal is still fragile, experts warn.

Dr Liz Allen, a demographer at the Australian National University, contends that Covid has already made the nation more “protectionist and insular”.

Government policies have created an “us and them” division, she argues.

The hostile treatment of migrants is a clear example, she says. Australia’s conservative government of eight years has never advocated for immigration – the coalition won the 2019 election pledging to “slash” the migrant intake.

At the start of the pandemic, Mr Morrison told the nation’s two million migrants on temporary visas to “go home”.

Those visa holders – often doing the low-paid, essential jobs of cleaning and food delivery – were also ineligible for the government’s pandemic welfare support, leaving many facing destitution.

The border ban has also sown community division, seen in its most extreme form last month when Australia took the world-first step of threatening jail for citizens who returned home from Covid-ravaged India. The Indian-Australian community expressed outrage they were being treated like second-class citizens.

Multicultural roots

The issue of stranded Australians reflects Australia’s character as an intensely multicultural nation.

Nearly 30% of the population were born overseas, and another quarter have a parent who was. As a nation of migrants, so many Australians have deep personal ties to other parts of the world.

Prior to Covid, about one million Australians were estimated to be living and working overseas. A section of the population – often highly educated and skilled – was also very mobile.

But the closed-border policy doesn’t appear to recognise these global connections or the disproportionate impact on first and second-generation Australians, critics say.

In addition, the borders created a narrative where blame for a virus outbreak was often laid at the feet of returning individuals.

“We turned on ourselves, on our own people,” says Dr Allen.

Political leaders described the virus as “imported” by returning travellers, rather than escaping through failures in the hotel quarantine system. Such rhetoric egged on social media commentary blaming incoming Australians.

Just happy to be safe

But while there’s division aimed at Australians outside the country, within the borders people feel comfortable with their lot.

First and foremost, people say they feel relieved and grateful to be shielded from the virus.

“There’s a lot of sympathy and real feeling for people caught up outside, and for the people who can’t go to weddings and funerals overseas,” says Melissa Monteiro, head of a migrant resource community centre in western Sydney.

“But you know, everyone ends with ‘that’s just how it is’. People are firstly, just grateful to be in this country and to be safe.”

Race relations researcher Andrew Markus, an emeritus professor at the University of Monash, says most Australians also don’t view the closed borders as a cultural isolation, or a “shutting yourself off from the world”.

Instead it’s just seen as a necessary short-term health measure – an attitude adopted across the political and cultural spectrum, he says.

He notes too that polling throughout the pandemic showed Australians’ support for multiculturalism and globalisation remained strong – about 80% approval – despite concerns about social cohesion and a rise in hate crimes against Asian-Australians.

Dr Allen says that the strong support for the government’s Covid fight is understandable – particularly when it has worked.

But she also says that the Australian public has been presented with no other options. The prolonged border closure and city lockdowns on single infections have all been largely uncontested policies.

She says it’s time now for Australia to move past such policies which she feels are rooted in fear. The country continues to face calls to bring back its own citizens.

“I don’t think it’s bad that people are afraid of Covid – we should be afraid. But we require leadership going forwards that doesn’t leave people behind.”

Source: ‘Fortress Australia’: Why calls to open up borders are meeting resistance