Chinese government-funded language and culture centres known as Confucius Institutes have rapidly closed down across the United States over the past four years amid pressure from the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the US Department of State, the US Congress, and state legislatures, concerned about China’s influence on universities.

Of 118 Confucius Institutes that existed in the US, 104 closed by the end of 2021 or are in the process of doing so.

Many institutions were forced to refund money to the Chinese government – sometimes in excess of US$1 million – according to a new wide-ranging report on Confucius Institutes (CIs) in the US by the National Association of Scholars, which was among the first to call for the closure of all Confucius Institutes on US campusesbefore the US Senate in 2019 called for greater transparency or closure.

However, “many once-defunct Confucius Institutes have since reappeared in other forms”, according to the association’s just-released report, After Confucius Institutes: China’s enduring influence on American higher education. It adds: “The single most popular reason institutions give when they close a CI is to replace it with a new Chinese partnership programme.”

US institutions “have entered new sister university agreements with Chinese universities, established ‘new’ centres closely modelled on defunct Confucius Institutes, and even continued to receive funding from the same Chinese government agencies that funded the Confucius Institutes,” it said.

“In no cases (out of the 104 institutions) are we sufficiently confident to classify any university as having fully closed its Confucius Institute.”

Rebranding and replacing

“Overall, we find that the Chinese government has carefully courted American colleges and universities, seeking to persuade them to keep their Confucius Institutes or, failing that, to reopen similar programmes under other names,” the report said.

American colleges and universities, too, appear eager to replace their Confucius Institutes with other forms of engagement with China, “frequently in ways that mimic the major problems with Confucius Institutes,” the report said. “Among its most successful tactics has been the effort to rebrand Confucius Institute-like programmes under other names.”

Some 28 institutions have replaced (and 12 have sought to replace) their closed Confucius Institute with a similar programme. Around 58 have maintained (and five may have maintained) close relationships with their former CI partner. About five have (and three may have) transferred their Confucius Institute to a new host, “thereby keeping the CI alive”.

Hanban, the Chinese government agency that launched Confucius Institutes, renamed itself the Ministry of Education Center for Language Education and Cooperation (CLEC) and spun off a separate organisation, the Chinese International Education Foundation (CIEF), that now funds and oversees Confucius Institutes and many of their replacements as part of a rebranding exercise in July 2020, designed to counter negative perceptions about CIs abroad.

“In reality, the line between the Chinese government and its offshoot organisations is paper-thin. CIEF is under the supervision of the Chinese Ministry of Education and is funded by the Chinese government,” the report noted.

Many CI staff migrated to CI-replacement programmes at the same university, according to the report which scrutinised a large number of contracts between CIs and US universities. It added that some CI textbooks and materials remain on the campuses of institutions that closed CIs.

The Chinese government has reacted by defending Confucius Institutes outright, but the report notes it has also “relied on the art of subterfuge, rebranding Confucius Institutes under different names and massaging their outlines to be less obvious to the public, and better camouflaged within the university”.

Three types of action were identified in the report: replacing the CI, maintaining a partnership in some way with the CI, or transferring the CI to a new home.

Replacing the CI

Many universities are eager to ditch the now-toxic name ‘Confucius Institute’ but retain funding and close relationships with Chinese institutions, the report noted.

“At least 28 universities replaced their Confucius Institute with a similar programme, and another 12 may have done so. Sometimes these replacement programmes are so closely modelled on CIs that we are tempted to call them renamed Confucius Institutes.”

Replacing the CI means the US institution “retained, on its own campus and as part of its own programming, substantial pieces of its Confucius Institute under a different name. This includes institutions that formed new replacement programmes with the Chinese university that had partnered in the Confucius Institute,” the report said.

It also includes institutions that formed new China-focused centres that took on Confucius Institute staff, Confucius Institute programmes, or funding from the CLEC or CIEF, the successors to Hanban.

For example, the University of Michigan, among others, sought to retain Hanban funding even after the closure of the Confucius Institute. Federal disclosures cited by the report show the university received more than US$300,000 from Hanban in May and June 2019, just as the Confucius Institute was closing in June 2019, though the report notes these disclosures have since been deleted from the Department of Education’s website.

Maintaining a partnership

While some Chinese partners reacted with shock at the notification to close the CI, and even threatened to sever all other connection between them and the US university host, setting up a new partnership with a Chinese institution is the single most frequently cited reason given by US institutions for closing a Confucius Institute, the report found.

Forty of 104 institutions (38%) say they are replacing the Confucius Institute with a new partnership, often one that is quite similar to the Confucius Institute. “Many others do in practice arrange for alternative engagement with China, even if they do not say this in the same statement in which they announce the closure of the Confucius Institute,” the report said.

The Chinese government often encouraged US universities, when they applied for a Confucius Institute, to first establish a sister university relationship with a Chinese university. For example, Arizona State University (ASU) became sister universities with Sichuan University, “having been led to believe that doing so would aid its bid to host a CI,” the report noted, adding that ASU did in fact establish a CI with Sichuan University, and the sister university relationship has survived the CI closure.

Upon closing a Confucius Institute, some US universities developed new partnerships with their Chinese partner universities, or maintained pre-existing partnerships outside the CI. Others transferred the CI to another institution, ensuring that the Confucius Institute did not really close but changed locations. Some universities engaged in several of these strategies at once.

The report tracked information for 75 of the 104 CIs that closed in the US. Of the 75, 28 replaced the CI with a similar programme, and another 12 sought to replace it, while 58 maintained relationships with their Chinese partner universities.

Many created something substantially similar to a Confucius Institute under a different name, as did Georgia State University, the College of William and Mary, Michigan State University and Northern State University.

The College of William and Mary replaced its CI with the W&M-BNU Collaborative Partnership in partnership with Beijing Normal University, its former CI partner. One day after the CI closed on 30 June 2021, the two universities signed a new ‘sister university’ agreement establishing the programme.

Chinese universities have also proposed programmes similar to Confucius Institutes but funded by the Chinese university itself. For example, Jinlin Li, president of South-Central University for Nationalities (SCUN), wrote to University of Wisconsin-Platteville Chancellor Dennis J Shields, suggesting that “we work together on a university level to continue to offer Chinese language credit courses and Chinese Kungfu programmes”. He added that “SCUN will gladly continue funding this operation”.

Replacing with another university programme

On being informed of CI closures, responses from Hanban “were initially characterised by shock and indignation, then by mere regret, and finally by well-coordinated efforts to woo colleges and universities into new partnerships”, the report said.

Richard Benson, president of the University of Texas at Dallas, wrote in a letter cited by the report: “We will be arranging a new bilateral agreement with Southeast University to continue our mutually beneficial engagements.”

Benson went on to describe the “newly created UT Dallas Centre for Chinese Studies” which would house many of the programmes the Confucius Institute once ran – the former director of the Confucius Institute heads this new centre.

Twenty-three universities said they would replace the Confucius Institute with their own, in-house programmes. However, 13 of these also said the CI would be replaced by a new partnership with a Chinese entity.

Ten of the 23 institutions announced plans to develop their own replacement programmes. Yet, at least four – University of Idaho, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, University of Montana and Purdue University – did in fact operate these programmes in partnership with their former CI partner.

Six universities–- Pfeiffer University, San Diego State University, the University of Maryland, the University of Arizona, the University of Washington and Western Kentucky University – said they intended to find a new home for the CI by transferring it elsewhere.

Reasons for winding down CIs

Most of the criticisms surrounding Confucius Institutes involve threats to national security, infringements of academic freedom, and the problem of censorship. But these are rarely the reasons colleges and universities give when they announce plans to close a Confucius Institute. The report found the most frequently cited reasons are the development of alternative partnerships with China, and changes in US public policy.

Only five of 104 institutions cited concerns regarding the Chinese government’s relationship to Confucius Institutes ¬– and two of these five proclaimed that all national alarm was due to the mismanagement of Confucius Institutes by other universities.

Citing letters that the institutions sent to the Chinese government or their Chinese partner university; letters sent to a US government body, internal announcements to the staff, faculty and campus community; and statements published on the institutions’ own websites or published by the media, the report found that replacing the Confucius Institute with a new Chinese partnership was the most popular reason given for closure, while the second most popular was US policy. Many gave no reason whatsoever.

Of the 33 colleges and universities that cite public policy as a reason for the Confucius Institute’s closure, 19 cite the potential loss of federal funds, and 11 specifically cite the National Defense Authorization Act, which barred certain grants from the Department of Defense to colleges and universities with Confucius Institutes. Three universities cited warnings they received from the US State Department.

Despite widespread public concern about the Chinese government’s ulterior motives for supporting Confucius Institutes, only five universities referenced these concerns. Two laid out possible problems with Chinese government interference but concluded this had not been the case at their university.

University of Wisconsin-Platteville Chancellor Dennis J Shields in a letter to CLEC and CIEF said: “Over the past two years, the United States of America and its Department of State have raised serious concerns as to the scope of the People’s Republic of China and Beijing’s influence over higher education institutions, both nationally and globally…

“Unfortunately, due to these recent and continued concerns raised by the United States federal government and public officials as well as the recently enacted legislation, I have reached the difficult decision to end the UW-Platteville Confucius Institute.”

Shields stressed though, that the University of Wisconsin had good experiences with Hanban.

Seven institutions said the Confucius Institute attracted too few students and others cited scarcity of funds as reasons for closure.

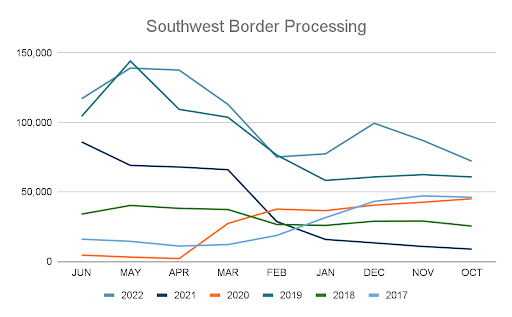

Given that Donald Trump failed to reduce illegal immigration the first time around, there is no reason to believe similar policies would succeed if tried again. During the Trump administration, between FY 2016 and FY 2019, apprehensions at the Southwest border (a proxy for illegal entry) increasedfrom 408,870 to 851,508—a rise of more than 100 percent. While the Covid-19 pandemic caused apprehensions to decline for several months starting in March 2020, by August and September 2020, apprehensions had resumed at the approximate level of illegal entry seen during the same months in FY 2019. In short, Donald Trump’s policies failed to reduce illegal immigration and were enacted at a great human cost, particularly for parents and children separated at the border.

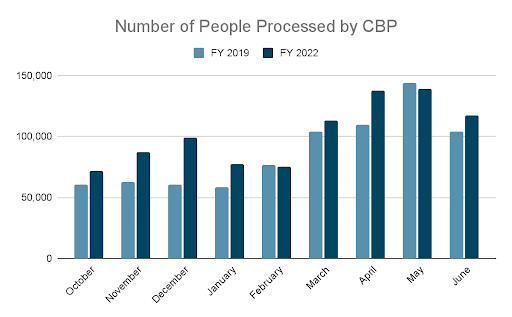

The Biden administration, in large measure, continued Trump’s border policies, namely Title 42, which allows individuals to be expelled without further processing. Title 42 is supposed to be a public health measure but has been used to prevent many people from applying for asylum. The policies have boosted Border Patrol apprehensions and encouraged people to enter unlawfully, often multiple times, likely making the border more problematic. A federal judge has ordered the Biden administration to keep Title 42 in place.