As the U.S. Unauthorized Population Expands, It Is Also Diversifying, New Fact Sheet Shows

2025/10/23 Leave a comment

Another informative MPI fact sheet. Would be nice to have an equally informative fact sheet or analysis for Canada rather than just a general number:

The unauthorized immigrant population has grown sharply, from 10.7 million in 2019 to 13.7 million as of mid-2023, MPI analysts find. Still, even as the unauthorized immigrant population has experienced the sharpest growth since the early 2000s, a full 80 percent have at least five years of U.S. residence—with 45 percent living 20 or more years in the United States.

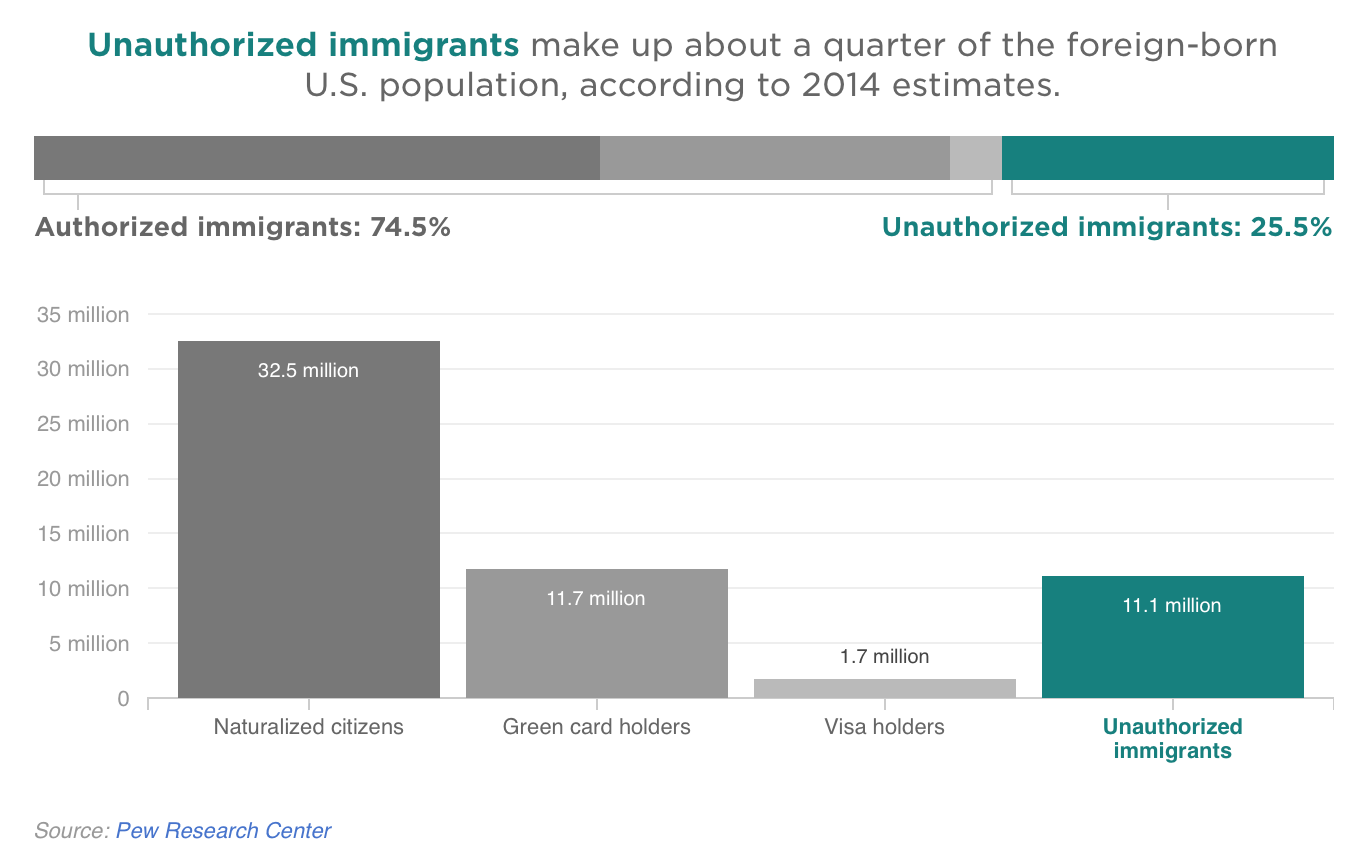

Unauthorized immigrants made up 26 percent of the overall immigrant population in the United States in mid-2023.

The fact sheet, Changing Origins, Rising Numbers: Unauthorized Immigrants in the United States, draws from a unique methodology that MPI created with leading demographers at The Pennsylvania State University and Temple University that allows the assignment of legal status in data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS). Given that the Census Bureau does not ask survey respondents if they are in the country without authorization, the resulting dataset offers a rare ability to study characteristics of the unauthorized population.

The fact sheet is accompanied by detailed data profiles of the unauthorized immigrant population at U.S., state and top county levels. The profiles include countries/regions of birth, ages, years of U.S. residence, top job sectors, workforce participation, educational enrollment and attainment, English proficiency, income, homeownership and access to health insurance, among other characteristics.

Among the key findings, all as of mid-2023:

- A growing share of the unauthorized immigrant population—as many as 4 million people, or 29 percent of the total—held a liminal (also known as “twilight”) status granting temporary relief from deportation and work authorization, through Temporary Protected Status (TPS), humanitarian parole, a pending asylum application or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA).

- Nearly 4.2 million unauthorized immigrants were married to a U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident (aka green-card holder). While marriage typically conveys the right to apply for legal permanent residence, most unauthorized immigrant spouses are unable to apply due to a 1996 immigration law.

- 6.3 million children under age 18 live with at least one unauthorized immigrant parent. All but 1 million of those children are U.S. citizens.

- 14 million U.S. citizens, green‑card holders or temporary visa holders share a household with an unauthorized immigrant.

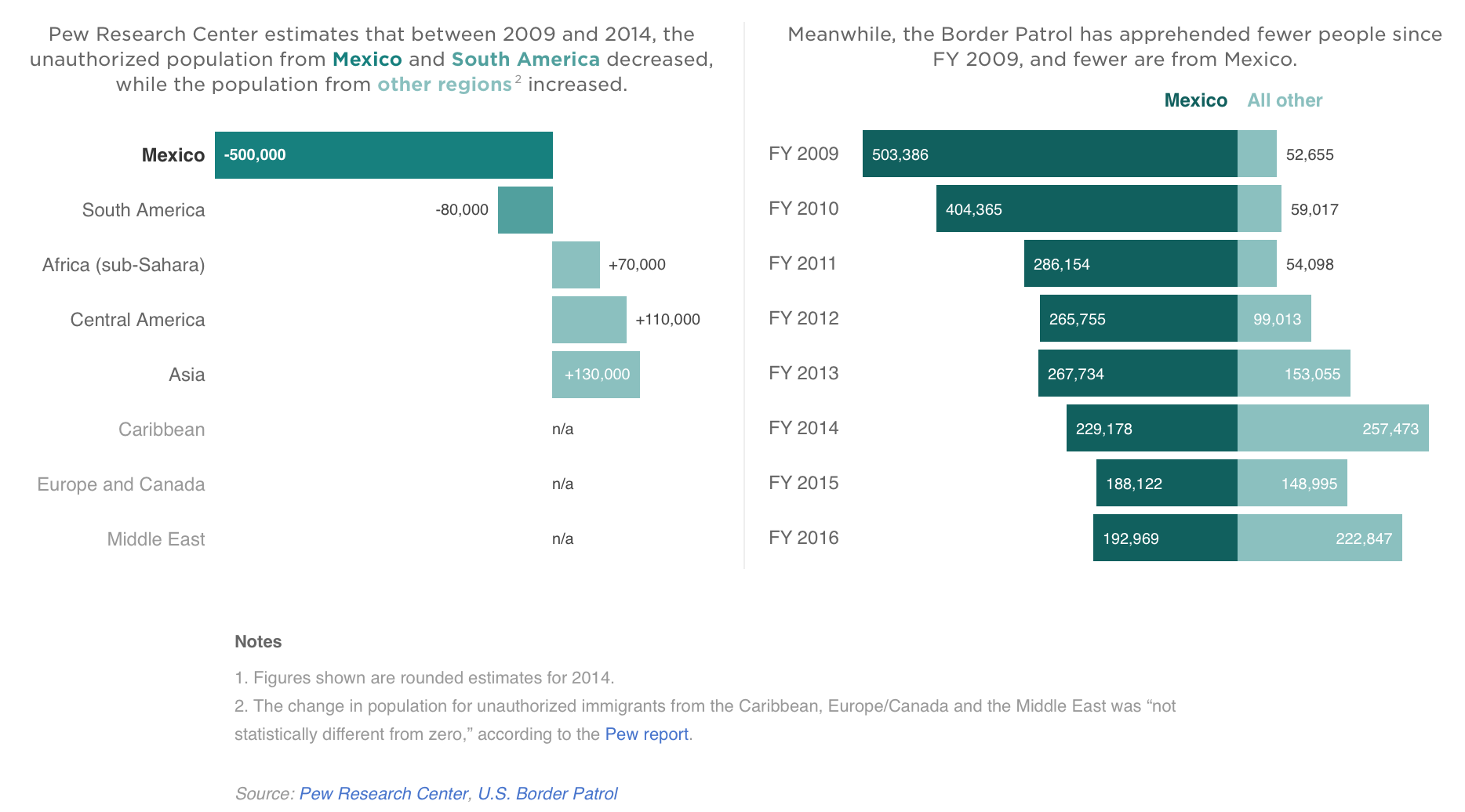

- Mexicans accounted for 40 percent of all unauthorized immigrants—down significantly from their 62 percent share in 2010.

- 21 percent of all unauthorized immigrants lived in California; overall, half lived in California, Texas, Florida or New York.

Source: As the U.S. Unauthorized Population Expands, It Is Also Diversifying, New Fact Sheet Shows