Trump Cut Muslim Refugees 91%, Immigrants 30%, Visitors by 18%

2018/12/10 Leave a comment

Stats are revealing:

On December 7, 2015, President Trump called for a Muslim ban. This ban later turned into “extreme vetting” policies, which—according to Trump—had the same goal. Now nearing the 2-year mark of his administration, an accurate assessment of these policies is now possible. All the major categories of entries to the United States—refugees, immigrants, and visitors—are significantly down under the Trump administration for Muslims or applicants from Muslim majority countries.

91% fewer Muslim refugees

President Trump has dramatically reduced the number of Muslim refugees. According to data from the U.S. Department of State—which records the religions of refugees—Muslim refugees peaked at 38,555 in fiscal year (FY) 2016, fell to 22,629 in FY 2017, and reached just 3,312 in FY 2018—a 91 percent decline from 2016 to 2018. Refugees of other faiths have also seen their numbers cut, though not to the same extent as Muslims. The share of refugees who were Muslims dropped from 45 percent in FY 2016 to 44 percent in FY 2017, and then again to 15 percent in FY 2018. President Trump has reversed the earlier trend under President Obama, where Muslim refugee admissions increased.

30% fewer immigrants from majority Muslim countries

Approvals for immigrant visas—that is, for permanent residents—for nationals of the 48 majority Muslim countries have fallen from 117,444 in FY 2016 to 104,228 in FY 2017 to 82,260 in FY 2018—a 30 percent drop overall. The share of new immigrants entering from abroad from majority Muslim countries has fallen as well, from 19 percent in FY 2016 to 18 percent in FY 2017 to 15 percent in FY 2018. This also reflects a change in the prior trend. From 2009 to 2016, immigrants from Muslim majority countries increased from 80,435 to 117,444.

The decline in immigrant visas occurred primarily in the family reunification categories, which President Trump refers to as “chain migrants.” From FY 2016 to FY 2018, the number of family-sponsored immigrants declined by 29,607—a 36 percent decline. Special immigrants—interpreters and other partners of the U.S. military mainly from Iraq and Afghanistan—accounted for the rest of the reduction. In FY 2018, there were 45 percent fewer immigrant visas for special immigrants than in FY 2016.

18% fewer visitors from majority Muslim countries

Though they were already relatively low to begin with, nonimmigrant visa approvals—temporary visas for workers, students, and tourists—from Muslim majority have also declined 18 percent from 2016 to 2018. In 2016, the Obama administration issued 856,886 nonimmigrant visas to nationals of Muslim majority countries. In 2017, this number fell to 718,535. By 2018, it had dropped to 702,375—154,511 fewer than 2016. The declines occurred among both tourist visas and other visa categories.

Explanations for the Decline in Visas and Refugees

Since President Trump establishes the refugee quotas for each region of the world and for each fiscal year, his decision to cut the quota and distribute the cap away from the Muslim world explains the drop in Muslim refugee issuances. For FY 2017, President Trump established the lowest refugee quota in the history of the refugee program.

The primary cause of the decline in the immigrant visa approvals is the travel ban that has singled out for exclusion eight majority Muslim countries since January 2017: Chad, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Syria, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen. Chad and Sudan have been completely removed from the list, and while Iraq is not officially designated, the latest proclamation from September 2017 singles Iraqis out for additional scrutiny.

The eight travel ban countries explain 65 percent of the decline in immigrant visa issuances for Muslim majority countries. Immigrant visa issuances for these countries have fallen 72 percent from FY 2016 to FY 2018. The travel ban explains only 28 percent of the decline in nonimmigrant visa issuances from Muslim majority countries. Nationals of the travel ban countries received 62 percent fewer nonimmigrant visas in 2018 than in 2016.

Beyond the travel ban, President Trump has imposed “extreme vetting” policies that make immigrating more bureaucratic and costly for everyone. He has massively increased the length of immigration forms, adding new subjective “security” questions. According to the American Immigration Lawyers Association, more applications for Muslims are disappearing into an “administrative processing” hole, where applications are held up for security screening. Undoubtedly, some Muslims simply want to avoid the United States where storiesof profiling and discrimination abound.

Conclusion

The bottom line is that the Trump administration is leading a major overhaul in the types of travelers, immigrants, and visitors who are coming to the United States. His administration reduced Muslim refugees by 91 percent and has overseen a 30 percent cut to immigrant visas for majority Muslim countries and an 18 percent cut to temporary visas. These policies lack a valid national security justification, but they are nonetheless having a significant effect. President Trump is certainly following through on his promise to limit Muslim immigration, even if a “total and complete shutdown” has not happened.

Source: Trump Cut Muslim Refugees 91%, Immigrants 30%, Visitors by 18%

M. Legault pourrait avoir plutôt fait allusion aux 26 % d’immigrants qui ont quitté le Québec, mais, dans ce cas, il omet de préciser que c’est entre 2006 et 2015 (soit sur 9 ans). Ce qu’il ne dit pas non plus, c’est que ces chiffres sont du ministère de l’Immigration et se basent sur les renouvellements de la carte d’assurance maladie, qui ne tiennent pas compte des décès et des non-renouvellements volontaires.

M. Legault pourrait avoir plutôt fait allusion aux 26 % d’immigrants qui ont quitté le Québec, mais, dans ce cas, il omet de préciser que c’est entre 2006 et 2015 (soit sur 9 ans). Ce qu’il ne dit pas non plus, c’est que ces chiffres sont du ministère de l’Immigration et se basent sur les renouvellements de la carte d’assurance maladie, qui ne tiennent pas compte des décès et des non-renouvellements volontaires. Brahim Boudarbat, professeur à l’École des relations industrielles de l’Université de Montréal, fait remarquer que, pour avoir l’heure juste, il faudrait uniquement s’intéresser à la catégorie des immigrants économiques, car ce sont eux qui sont sélectionnés avec, notamment, le critère de la langue française. Et là, toutefois, les politiciens n’auraient pas tort de s’alarmer sur la proportion d’immigrants francophones, qui sont en diminution constante depuis ces dernières années, passant de 67 % en 2012 à 53 % en 2016. « Ça, c’est un problème, puisqu’on voit que ça baisse », dit-il. Le ministère de l’Immigration a reconnu qu’elle avait admis un plus grand nombre de personnes déclarant uniquement connaître l’anglais, notamment parce que l’adéquation entre les besoins du Québec dans certains secteurs d’emploi et les compétences des travailleurs migrants était devenue plus importante que le seul critère de la langue.

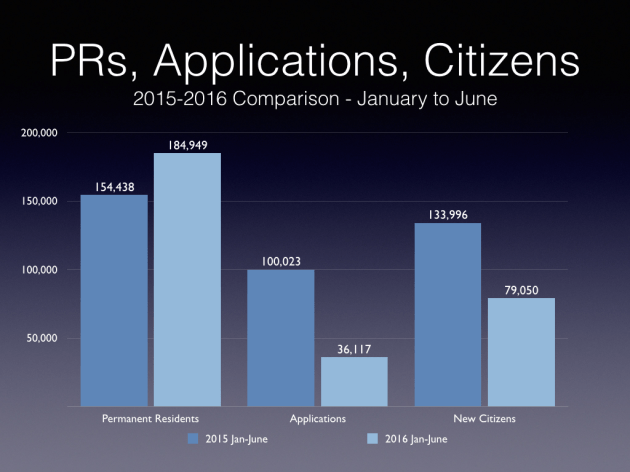

Brahim Boudarbat, professeur à l’École des relations industrielles de l’Université de Montréal, fait remarquer que, pour avoir l’heure juste, il faudrait uniquement s’intéresser à la catégorie des immigrants économiques, car ce sont eux qui sont sélectionnés avec, notamment, le critère de la langue française. Et là, toutefois, les politiciens n’auraient pas tort de s’alarmer sur la proportion d’immigrants francophones, qui sont en diminution constante depuis ces dernières années, passant de 67 % en 2012 à 53 % en 2016. « Ça, c’est un problème, puisqu’on voit que ça baisse », dit-il. Le ministère de l’Immigration a reconnu qu’elle avait admis un plus grand nombre de personnes déclarant uniquement connaître l’anglais, notamment parce que l’adéquation entre les besoins du Québec dans certains secteurs d’emploi et les compétences des travailleurs migrants était devenue plus importante que le seul critère de la langue. The chart above, year-to-year comparison, shows the expected drop (41 percent) in the number of new citizens following IRCC’s success in 2014 and 2015 in eliminating the backlog (from a high of 323,000 in 2012 to 59,000 on 30 June 2016).

The chart above, year-to-year comparison, shows the expected drop (41 percent) in the number of new citizens following IRCC’s success in 2014 and 2015 in eliminating the backlog (from a high of 323,000 in 2012 to 59,000 on 30 June 2016). Canada used to publish statistical reports that were every bit as good as the Americans’ — in some cases, better. Then we stopped.

Canada used to publish statistical reports that were every bit as good as the Americans’ — in some cases, better. Then we stopped.