SEAN SPEER: As you know, the Canadian Century Initiative, a non-profit organization dedicated to the goal of raising Canada’s population to 100 million by 2100 through large-scale immigration, recently released new polling in conjunction with the Environics Institute for Survey Research. I want to start by asking for your reaction to the survey’s top-line finding. There has been a significant increase—indeed, the largest year-over-year increase since Environics started asking this question in 1977—in the percentage of respondents who believe that Canada has too much immigration. What do you think about this result? Are you surprised? And what do you think is behind it?

MIKAL SKUTERUD: While Canadians have always been, and continue to be, overwhelmingly open to immigration, opinion polls have long shown that a significant majority of Canadians believe the number of immigrants Canada accepts should be limited. I think this reflects a widespread belief that while immigration has the potential to boost average economic well-being in the population, there is a limit to that potential. The vast majority of Canadians understand that the economy has an absorptive capacity. When the population grows faster than the housing stock, public infrastructure, and business capital, there is less capital per person, and this tends to lower labour productivity and average economic living standards in the population. My best guess is that the shifting sentiments that Environics is seeing in their polling reflect concerns that the government’s ambitious immigration agenda is pushing up against the economy’s absorptive capacity.

SEAN SPEER: The biggest explanation for the increase in the public’s misgivings about immigration is the perceived effect on housing prices. This ought to have been a predictable concern among policymakers and the Canadian Century Initiative itself. Why do you think we failed to account for housing demand and the need for greater supply in conjunction with raising immigration levels? What can be done to improve jurisdictional coordination and coherence on these issues?

MIKAL SKUTERUD: In 2015, an economic narrative surfaced in this country that claimed heightened immigration rates, from what were already high rates when compared to other OECD countries, would be a tonic for economic growth. Canadians were told that higher population growth would not only make Canada more prosperous but that higher immigration was necessary for economic growth. For economists like me, who have been studying the economics of Canadian immigration for decades, these hyperbolic claims did not line up with the predictions of standard economic models of economic growth or with the Canadian empirical evidence.

In March 2016, then Minister of Immigration, John McCallum, invited a group of us to share our views. In retrospect, it’s clear that our concerns fell on deaf ears. The immigration narrative was a feel-good story, and nobody likes a cold shower. The appeal of the narrative that immigration—“Canada’s secret sauce”—could be the solution to our dismal economic growth and labour productivity performance is understandable. But, of course, sometimes political narratives are so appealing that well-intentioned people get caught up in the warm feelings of what we’d like to be true and lose sight of the more important question of what is true.

If we know nothing else about the economics of immigration, we know that immigration has distributional effects. In general, the folks who are on the opposite side of consumer and producer markets of immigrants stand to benefit, while folks on the same side are likely to experience adverse economic effects. While recent immigrants who live in the same communities as newcomers face heightened competition for housing and jobs, the competitive pressures facing sellers in mortgage markets (banks) and buyers in labour markets (employers) are alleviated.

An interesting result from the recent Environics poll which I haven’t heard any media report on is that the biggest shift in dissatisfaction with recent immigration levels is among first-generation immigrants. This is consistent with the proposition that population growing pains are likely felt most by immigrants already here. To the extent that we care about the consequences of heightened immigration on economic inequality and social cohesion, these distributional effects should be of first-order concern to policymakers.

SEAN SPEER: One of the issues that, according to the polling, is the subject of declining public confidence is the notion that we need or want a larger population itself. A lot of the immigration debate is implicitly motivated by the idea that we should aspire to a fast-growing and larger population. What is your view on this question? What does the scholarship tell us about the benefits of bigness? Should we have an explicit goal for Canada’s population to become larger?

MIKAL SKUTERUD: The economic case for bigness is most often made with reference to what economists call “agglomeration effects.” The general idea is that bigger cities with higher population densities are more successful in generating the flows of knowledge and ideas that result in innovation, and in turn, technological advances, and growth in total factor productivity. This mechanism could, in theory, be a source of increasing returns to scale, such that a two percent increase in the inputs that go into producing aggregate output, most importantly the labour input, result in a more than two percent increase in aggregate output. In this way, an increase in the immigration rate can produce an increase in GDP per capita.

Unfortunately, I’m unaware of any credible evidence that this mechanism has been important in recent Canadian history. Certainly, the current push to settle more immigrants in remote communities works against this mechanism. In work with my colleague Joel Blit and recent Ph.D. student Jue Zhang, we examined the relationship between inflows of university-educated immigrants into Canadian cities to the number of new patents created in those cities and found no evidence consistent with the proposition that agglomeration effects have been quantitively important for Canada historically, in contrast to the results of a similar analysis using U.S. data.

Perhaps a more compelling argument for why population size is, in itself, a sound economic objective is that bigger countries have more geopolitical influence on the world stage and that this advantage somehow benefits economic growth through more advantageous free trade deals, for example. However, if this mechanism was quantitatively important, we’d expect countries with larger populations to be on average richer, but the opposite is true. World Bank data from 187 countries in 2019 shows that the correlation between national population and GDP per capita is unambiguously negative. Many big countries are poor, and many small countries are rich.

SEAN SPEER: One of the most interesting results is that 77 percent of respondents said that government policy should prioritize high-skilled immigration. Only one-third said that it should prioritize low-skilled workers and students. Yet as your work has shown, government policy has tilted away from high-skilled immigration to the latter two categories in recent years. How does one explain that dissonance and what should be done to rebalance the composition of Canada’s different immigration streams?

MIKAL SKUTERUD: The repair to the permanent immigration system is simple: return to a single pathway for economic-class immigration with a single selection criterion. This is what we had in Canada before 2021. All economic-class immigrants (outside Quebec) received permanent residency status by entering the Express Entry pool where they were assigned a Comprehensive Ranking System (CRS) score, which is essentially a prediction of the applicants’ future earnings in Canada. Every two weeks, IRCC announced a CRS cutoff score and candidates with scores above the cutoff were invited to apply for PR status.

However, since 2021 IRCC has introduced a series of ad-hoc TR-to-PR pathway programs intended to provide PR pathways for applicants with low CRS scores. For example, in April 2021, they announced a new PR pathway for 90,000 temporary workers employed in a list of “essential occupations” that included cashiers, cleaners, truck drivers, construction and farm labourers, and security guards. More recently, the Category-Based Selection System has been introduced allowing the minister of the day to bypass the CRS criterion to prioritize any occupation in the applicant pool. This flexibility enables the Minister to respond to business lobbying pressure for more low-skilled labour. This politicization of immigrant selection isn’t good for wage growth in Canada’s low-skilled workforce and undermines business incentives to invest in training and technologies to improve labour productivity.

The question of whether immigration should be focused on raising the average human capital stock of the population or plugging holes in current labour markets is longstanding. Economists have overwhelmingly argued for the former approach. Their logic is simply that we don’t believe planned economies work well. There is overwhelming evidence that aggregate production in modern economies doesn’t require some fixed ratio of labour types. In 1921, one-third of Canada’s workers were employed in agriculture. After more than 100 years of innovation in farming equipment, less than two percent are. Trying to predict where job vacancies will be in five or ten years is futile because labour demand is endogenous to labour supply. Where a particular labour type is plentiful, wages will be low, incentivizing employment of those types, and where a labour type is scarce, wages will increase, incentivizing substitution to other types of labour or capital investments. If we want a low-wage low-skill economy, we should target low-skill immigrants; but if we want a high-skill high-wage economy, we should prioritize high-skill immigrants.

SEAN SPEER: More generally, if you were advising government policymakers on their policy response to these findings, what might change? Should we lower our permanent resident target? Should we prioritize addressing the growth in non-PR streams? Should we do both? What is the Skuterud plan to restore public support for high levels of immigration?

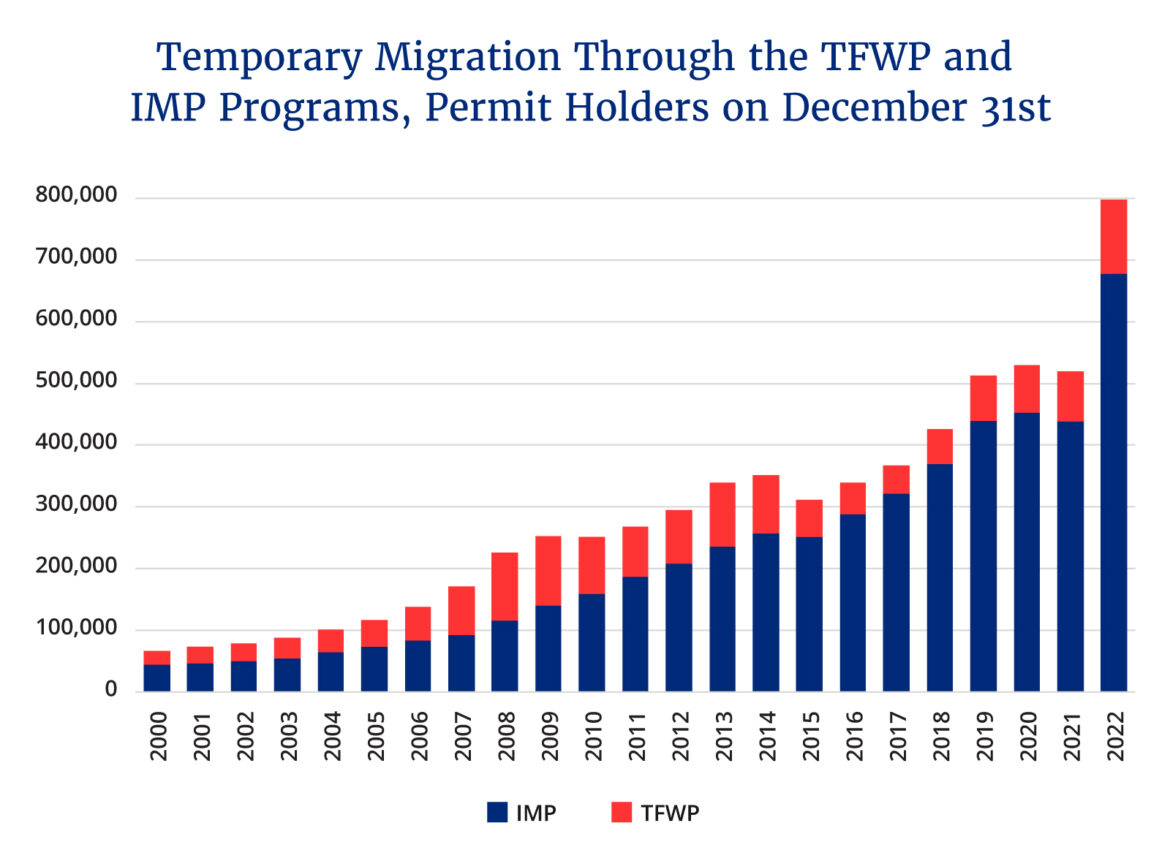

MIKAL SKUTERUD: A positive outcome of the growth in Canada’s foreign student and temporary foreign worker populations is it has justified a call for better data. Statistics Canada now publishes a quarterly data series on the overall size of Canada’s non-permanent (NPR) population. This population is exceptionally difficult to measure but they have taken a good shot at it. What the data show is that Canada’s NPR population increased from 1.5 million to 2.2 million—a nearly 50 percent increase—between July 2022 and July 2023.

As the NPR population grows faster than the number of new PR entries, an increasing number of temporary residents who came to Canada with dreams of settling permanently will find their permits expiring before they’ve made the transition. This inevitably means that Canada’s undocumented population will grow. A growing undocumented population is undesirable for many reasons, so rebalancing growth in Canada’s NPR population with the growth in Canada’s PR targets should be, in my view, a first-order priority for IRCC.

At the core of the challenge here are two realities. First, Canadian permanent residency status holds enormous economic value to huge populations of individuals around the world. Second, Canadian immigration policy has over the past decade shifted in a significant way to “two-step immigration” in which the pathway to PR status is to study or work in Canada as a temporary resident and then clear the hurdles of the PR admission system. Together these realities mean that a key factor in migrants’ private cost-benefit decisions to come to Canada is their perception of the likelihood of making a successful TR-to-PR transition while in Canada.

While increasing TR-to-PR pathways for migrants may be well-intentioned, an unintended consequence of these programs is they increase the odds that lower-skilled migrants will get lucky and obtain PR status. In this regard, they serve to lure migrants who are willing to pay exorbitant tuition fees to postsecondary institutions that offer little educational value and or accept jobs offering substandard wages and working conditions. There’s little doubt in my mind that an important cause of the tremendous growth in the NPR population is a supply-driven response to migrants’ perceptions that their chances of winning the PR lottery have increased in recent years. Fixing this problem requires returning to a single PR pathway that is transparent and predictable and that prioritizes applicants with the highest CRS scores.