The pandemic blew up the norms and structure of work behaviour in Canada’s public service and now bureaucrats want new rules and a say in how work fits into their lives as the federal government readies for a return to the office.

Everything about working in the public service is up for grabs.

After nearly two years, the pandemic proved public servants can work in many jobs from anywhere. That’s upended the conventional approach to work, including the 37.5-hour work week, endless in-person meetings, a soulless cubicle culture and how to climb the hierarchy. It’s an opportunity for change reformers have dreamed about for 25 years.

“Look, if I could press an undo button and make sure COVID never happened, I would… but it happened, and the silver lining is we have exponentially adopted telework,” said Dany Richard, a union president and co-chair of the National Joint Council, a joint union and management committee. “That allows us now to reassess how the future of work will be.”

With a global talent shortage and an economy favouring workers, public servants couldn’t be in a better position to make demands on their employer about their future work lives.

There are high hopes for a new telework policy being hashed out behind closed doors with unions and senior management. Advocates promise a new mobile workforce that would break the Ottawa-Gatineau monopoly on headquarter jobs. It would improve workforce diversity and work-life balance and reduce real estate and operational costs along with pollution from commuting.

The pandemic also picked up the pace of digital transformation of the public service by three to five years, said Ryan Androsoff, director of digital leadership at the Institute on Governance.

In a blink, public servants went en masse to work at home. After a mad scramble for enough laptops, bandwidth and network access, public servants learned to work in real time, mastering videoconferencing, text and chat software and editing documents collaboratively.

“It would have taken multiple years before departments would have reached the point where 100 per cent of their workforce could work in a distributed and remote way,” Androsoff said.

Public servants aren’t expected to return to offices until the pandemic is declared over, but everyone is braced for a hybrid workplace, a mix of working in office and at home.

Is government ready? Not quite. The Treasury Board’s Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer is putting together a short- and long-term plan for the future of work with a “spotlight on telework” that rolls out as COVID restrictions are lifted and public servants can return to in-office work.

Richard argued working remotely during an emergency like the pandemic worked because everyone is in the same boat. The challenge now is how to “optimize” remote work and make the most of it.

“I think the employer will generally be open to telework,” said Richard, who is president of the Association for Canadian Financial Officers. “I don’t think it’ll be 100 per cent of the time. But as long as an employee commits to, I’d guess, two days a week in the office, the employer will say, ‘Okay let’s try three days at home and two days in the office.’”

Not all federal jobs can be done from home. Ship crews, prison guards, border guards and meat inspectors can’t. Call centres, science laboratories and operations like the Canada Security Establishment need people at the workplace.

Most office workers, however, don’t want to return to the old ways. Surveys found most want to work from home full-time or several days a week. As one senior bureaucrat said, the “pinch point” is whether location of work is an employee’s right or preference. Or is it an “operational requirement” that managers should define?

“We just spent a year and half working from home on a mandatory basis. We had to work from home. Employees see the benefits and want the flexibility to choose where they work,” said Stéphane Aubry, vice-president of the Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada (PIPSC).

As part of that flexibility, Aubry said the union wants jobs classified as remote or telework positions and no longer attached to a city or a building. It argues the government should pick up some of the cost employees bear working at home. It also wants all tasks and activities that have to be done at the office clearly laid out.

“We want a position to be officially classified as a telework job so when there’s a job opening it is put on paper as a telework job,” said Aubry. The government can then look for employees across Canada. It would change the way they do recruitment.”

At the moment, Treasury Board has left it up to departments to decide how their employees will work. The board sets guidelines but deputy ministers are responsible for how their departments run.

Some have already indicated they want workers back in the office some of the time; others are encouraging people to work from home full-time or to decide where they want to be based. Departments like Transport and Public Services and Procurement Canada have been singled out as among the most flexible. Meanwhile, unions are irked the RCMP have ordered some civilian employees back to the office before restrictions have been lifted.

That’s why some are looking for a more consistent policy. One senior bureaucrat said the approach is too “muddied” and sets the stage for expectations and conflicts between departments and unions.

“Instead of having a common approach they’ve left it scattered, which is a problem because deputy ministers are not willing to make a decision that might be precedent-setting and everybody gets stuck,” said the bureaucrat, who we are not identifying because he is not authorized to speak on the subject.

A big challenge with hybrid work is how to treat everyone equitably. The unions are worried about two tiers of employees: those who work in-office and those who don’t. It’s expected those who work in the office, where they are known by management, will have an edge for promotions and special projects.

What if deputy ministers and other senior executives return to the office? Won’t more employees follow suit and come to the office to be seen?

It could create a gender gap for women, who are disproportionately drawn to remote work to better manage parenting or other caregiving needs they juggle.

“I would love to see a situation where if government goes to a hybrid model that they actually say everybody in the organization has to work remotely two or three days a week, so that everybody’s having that same experience,” said Androsoff.

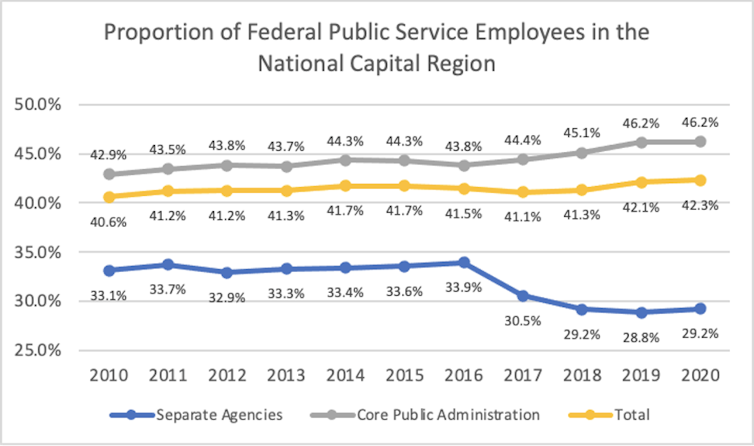

Nearly 42 per cent of public servants work in the National Capital Region. Stories abound of public servants who moved to the countryside or to the east or west coasts to work remotely during lockdown and have no plans to come back. Managers started filling Ottawa jobs with people outside the region and not requiring them to relocate.

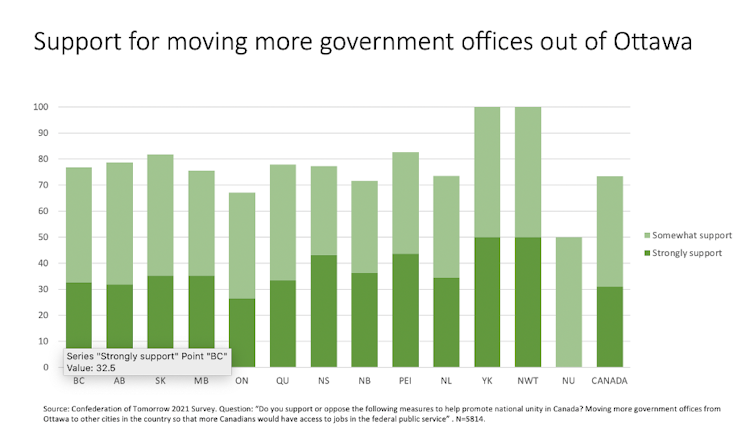

There are far more ministers and MPs from outside Ottawa who have long tried to decentralize federal jobs to the regions. The argument for the capital’s disproportionate share of jobs was based on the location of Parliament, ministers and senior management. If the pandemic allowed MPs and Parliament to meet virtually, why wouldn’t they press for more jobs to be done remotely?

Former privy council clerk Michael Wernick says relocating Ottawa jobs is inevitable, adding it could happen in a “very conscious way” or “by stealth.” There are plenty of examples of departments operating outside the capital – Veterans Affairs in Charlottetown, Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency in Moncton, National Energy Board in Calgary or the pay centre in Miramichi.

“The political pressure for geographic decentralization, plus work moving out to people’s homes, means a much less gravitational pull from Ottawa,” said Wernick.

“Maybe it won’t be the big departments and central agencies in the core public service, but there are 300 federal entities. And I think they may start maybe with some of those. Why does a tribunal, for example, have to hold hearings in Ottawa?”

Remote work would attract a more diverse pool of applicants who better represent Canada, including those who don’t live in urban centres, Indigenous people, visible minorities and people with disabilities.

A national recruitment strategy, however, will quickly collide with the public service’s bilingualism requirements.

“It opens doors for people from across the country to be part of the federal government in a way never possible before, but how to do that with existing bilingual policies is going to have to be explored,” said Androsoff.

A new telework policy assumes managers will shift to results-based management and hold people accountable for what they do and not just showing up for work.

But Wernick said the public service must sharpen its competitive edge to keep and attract employees in a global talent shortage. That shortage could worsen with an exodus of public servants, burned out and ready to leave after two years of going full tilt in the pandemic. Others put off retirement during lockdown and will leave rather than go back to the office.

Many argue departments will offer remote work to attract and retain people. That could also spark an internal war for talent as people flee to departments that offer the most flexibility and remote work.

The government’s technology is still years behind the private sector, but the pandemic brought all public servants to a basic level of digital literacy with new skills they want to use. Some argue home network and internet connections are now much better than what employees had at the office.

Canadians also have much bigger expectations of government. They are living more digitally now, banking and shopping online, and expect the same easy and rapid service from the government.

But Androsoff said there’s still a powerful pull from the traditionalists who would rather return to the old ways: nine to five, back to the office, in-person meetings and assigned desks.

“The federal government, by virtue of its size and history, has institutional inertia. In previous waves of reform, that inertia always pushes to go back to the way it was,” said Androsoff.

“I’m hoping for lasting change, but it remains to be seen whether this push is permanent or the pressure to go back to its institutional comfort zone wins the day.”