The statisticians describe the unprecedented number of people streaming into B.C., while the province’s mayors explain how difficult and costly it is to try to house everyone.

A special housing meeting of the Union of B.C. Municipalities heard this week that B.C.’s population has jumped like never before — and that more than 600,000 new dwellings are needed just to get back to supply and demand ratios similar to a couple of decades ago.

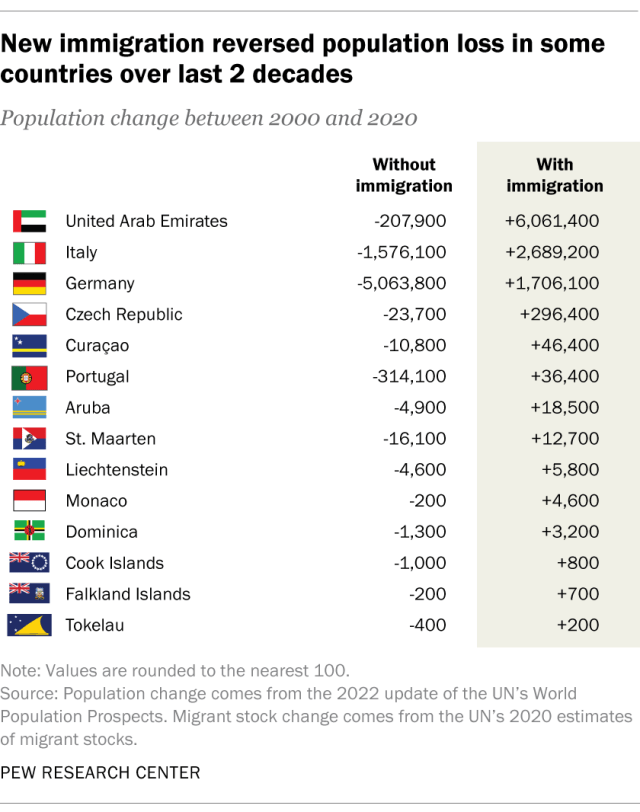

“All of our growth is international,” said Brett Wilmer, B.C.’s director of statistics. B.C.’s population would basically remain flat, Wilmer said, if it weren’t for the dramatic hikes it has experienced in permanent residents, and especially of foreign students and guest workers.

More than 80 per cent of B.C. newcomers are moving to Metro Vancouver, Victoria, the Fraser Valley and the Central Okanagan, said Wilmer.

While B.C.’s population expanded by a near-record three per cent last year, an economist for the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Braden Batch, said new housing supply is not matching outsized demand.

“Population growth has put real strain on the housing system. It’s a massive problem,” said Batch, adding new dwellings would have to be built 2.5 times faster to keep up.

The hundreds of mayors, councillors and urban planners attending the UBCM housing summit were told that B.C.’s population will grow by almost one million in the next eight years.

Batch’s charts showed that, under current scenarios, B.C. is set to have a housing shortfall of 610,000 units by 2030.

That prompted the director of Simon Fraser University’s Cities Program, Andy Yan, to say: “We’re going out to offer the Canadian dream to people around the world, but we seem to be OK throwing them into a housing nightmare.”

B.C.’s mayors described how hard it is to get developers to build affordable new housing. They also warned it is costly for taxpayers to provide the transit, sewer systems, schools and medical care to support prodigious population growth.

During a panel titled “Housing the Next Million British Columbians,” five mayors from across the province expressed decidedly mixed feelings about the way B.C. Premier David Eby and Housing Minister Ravi Kahlon last year pushed through sweeping legislation to respond to dramatic urban population growth.

While some mayors complained they weren’t consulted, the B.C. government is now requiring municipalities to allow between three and six units per lot in virtually all low-density residential neighbourhoods, plus highrises near the transit hubs of 31 towns and cities.

Despite some mayors expressing cautious support for Victoria’s plan, they nevertheless said they didn’t think it would improve affordability.

Instead, the mayors described the high cost of supporting more people in more congested neighbourhoods, and expressed dissatisfaction about overstretched staff, loss of green space, parking debacles and a dire shortage of construction workers.

Burnaby Mayor Mike Hurley said it will cost taxpayers an average of $1 million to upgrade a typical 100-metre row of detached houses to provide the infrastructure for four- and six-plexes.

“I’m also not sure we have the workforce, the tradespeople, to do it,” said Hurley, remarking that “hopefully half of the those million more people who are arriving will be in the housing construction industry.”

Both Hurley and Richmond Mayor Malcolm Brodie said the NDP’s push for multi-unit housing throughout cities is creating chaos for their long-range community plans, which have emphasized high density around SkyTrain lines and certain town centres.

“The densification we’ve done is really stark,” said Hurley, referring to massive new skyscraper clusters Burnaby has encouraged at Metrotown, Brentwood and Lougheed town centres.

Citing Richmond’s much-praised Steveston, a community with detached homes on small lots on the south arm of the Fraser River, Brodie argued the B.C. government’s mass upzoning scheme “will destroy a fine neighbourhood.”

None of the five mayors on the “Housing the Next Million British Columbians” panel believed that efforts to increase housing supply will actually lead to affordable dwellings for middle-class and other families.

In recent years, Brodie said, Richmond “has built 50 per cent more housing units than the population has grown. But prices have still gone up by 60 per cent. It simply does not follow that supply reduces prices.”

Bluntly, the mayor of Burnaby added: “The idea that supply will lead to affordability is an absolute fallacy.”

Although speakers agreed projections about the future are hard to get right, Hurley suggested it’s possible development could slow down.

That echoed Wilmer, who told delegates the huge spike in foreign students and guest workers approved by Ottawa in the past two years should “drop back to historical levels this year and next.”

Such non-permanent residents put the most pressure on rental costs, which are at record highs in Metro Vancouver.

While Victoria Mayor Marianne Alto talked about how accommodating vigorous population growth means her city “can only go up, up, and only go in-fill,” Janice Morrison, the mayor of 11,000-resident Nelson, lamented the inevitable “loss of urban green spaces, which is a big reason a lot of people move to smaller cities.”

Richmond’s mayor disagreed over parking with Nathan Pachal, the mayor of the City of Langley. Saying it costs $90,000 to create one parking space, Pachal supported the NDP’s plan to drastically reduce off-street parking for new multi-unit housing buildings. But Brodie said it will create a parking nightmare.

Meanwhile, Nanaimo Mayor Leonard Krog was among those expressing guarded support for the provincial government’s aggressive “good intention” to provide shelter to more people through blanket upzoning.

Like some others, however, Krog suggested the strongest hope for creating more units, especially of the affordable kind, lies in government-subsidized housing — especially from the national government, which he said got out of housing incentives 30 years ago.

All in all, the mayors called firmly on the federal Liberals to show more common sense. That means, they said, Ottawa must be more pragmatic in aligning its international migration targets with the ability to provide housing for all.

Source: Douglas Todd: Record population growth ‘massive problem’ for housing in B.C