A Toronto principal’s suicide was wrongly linked to anti-racism training. Here’s what was really said

2023/07/29 Leave a comment

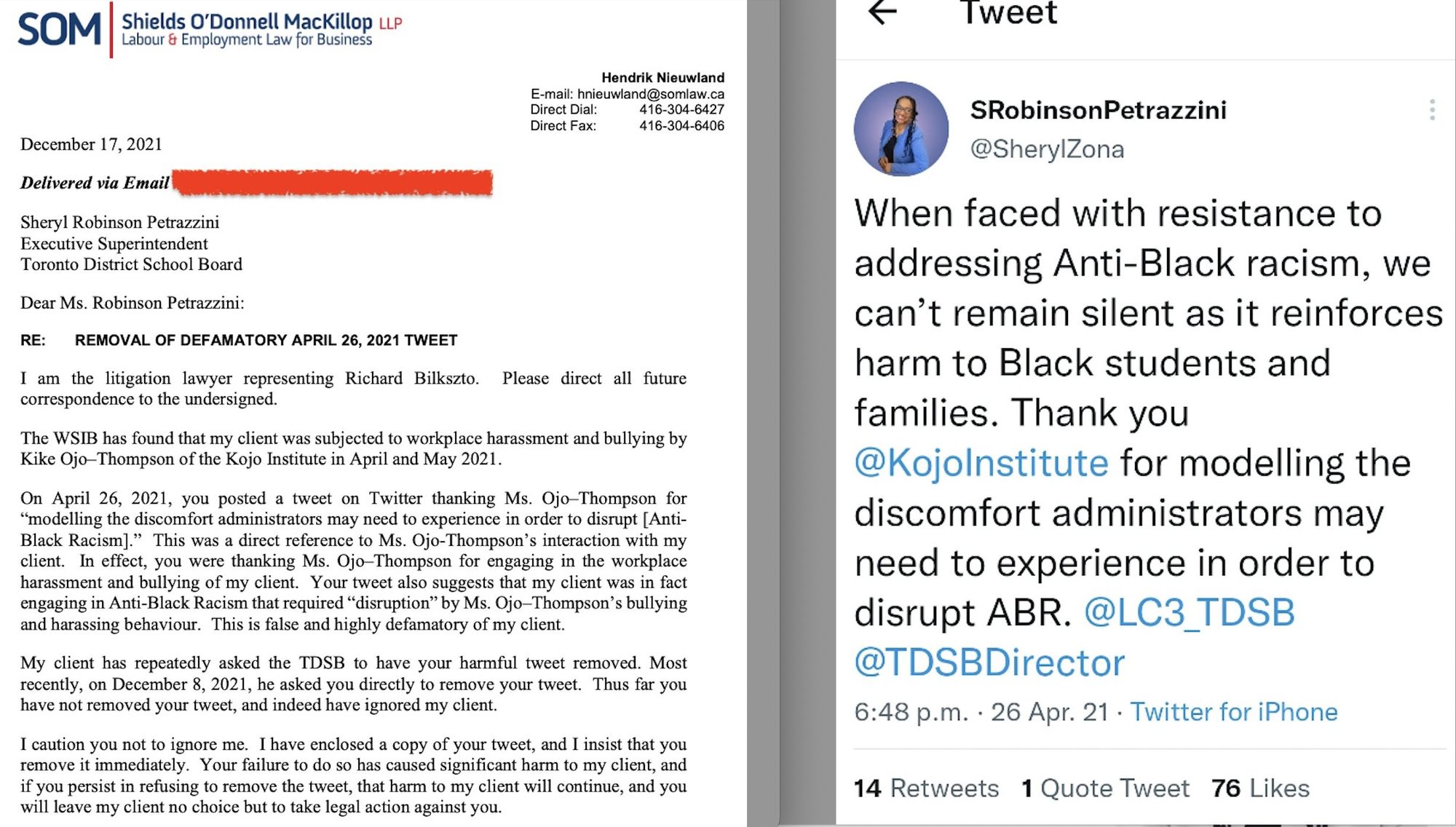

The alternative reflexive perspective but one that discounts the assessment by the WSIB (Workplace Safety and Insurance Board). And just as Paradkar can state “government organizations are often given credulity even when not merited,” the same can often be said for DEI consultants and activists:

One man’s fatal mental health crisis has been co-opted by political opportunists and turned into an attack on anti-racism training while also, chillingly, targeting one Black woman.

Former Toronto school principal Richard Bilkszto, 60, ended his life July 13. Suicide is a horrendous loss, no ifs, no buts. It’s terrible to contemplate the mental torture that leads to that decision and terrible to experience its crushing aftermath.

While experts say suicides are rarely caused by single factors, the man’s lawyer linked his death to a 10-minute interaction two years ago at a mandatory Toronto school board training run by the highly respected Kike Ojo-Thompson of the KOJO Institute, and her subsequent reference to that interaction.

His lawyer, Lisa Bildy, said in a tweet, “He experienced an affront to that stellar reputation” at that workshop and “succumbed to his distress.”

The predictable backlash from the right rested its moral might on two claims:

- a statement of claim after Bilkszto filed a civil lawsuit against the TDSB in April for not defending him in that workshop; and

- the opinion of an insurance case manager at the WSIB (Workplace Safety and Insurance Board) that allowed Bilkszto to file a claim for mental stress injury in August 2021. The case manager wrote that Ojo-Thompson’s conduct “was abusive, egregious and vexatious, and rises to the level of workplace harassment and bullying.”

This was not a finding based on a credible investigation, but government organizations are often given credulity even when not merited. In a statement on the KOJO website Thursday evening, Ojo-Thompson, who has done training at the Star previously, said she only heard about the lawsuit through media enquiries. “Additionally, KOJO was not part of the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) insurance claim adjudication.”

At issue, based on news reports, were two statements. One, Ojo-Thompson challenging a beloved Canadian myth by stating “Canada is more racist than the United States” and, two, “reacting with vitriol” when the former principal objected as well as “humiliating” him by calling him a “white supremacist” and a “resistor.”

The Star obtained a copy of the recording of the two sessions in question from a source who was present at the meetings. Based on it:

Ojo-Thompson never said: “Canada is more racist than the United States.”

She never called Bilkszto a “white supremacist and resistor.”

The recordings reveal for the first time a fuller picture of the conversation and disagreement that has been cherry-picked, shorn off context and nuance, and presented by those with an agenda to villainize diversity initiatives.

They show that the Canada-U.S. comparisons — although perfectly legitimate — were not initiated by Ojo-Thompson but were repeatedly brought up by participants in the “questions, comments, aha-s” that she invites.

For instance, one white TDSB leader says reflectively: “We as Canadians like to say we’re not as bad as our neighbours to the south and we need to stop.” Another leader brings up an example of a Black person from the U.S. moving to Canada “in hopes of a better future for her two sons,” and says “she was furious with me. She said, ‘I thought it was better up here. … I cannot believe it’s worse.’”

In response, Ojo-Thompson leans on her personal experience as a Black woman to say: “I felt more normalized as a Black woman there than I do here. We’re invisibilized from the cultural fabric of this nation. Canada has never reckoned with its anti-Black history,” and, “I lived in the South. And I’m saying this factually without any hiccup. The racism we experience is far worse here than there.”

There is a vast difference between a Black woman comparing her personal experiences of racism in two countries and a blanket statement that one is worse than the other.

About 10 minutes before the session ends, Bilkszto speaks for the first time. He says he spent a lot of time in the U.S. and, “I invite everyone here to do some research and look at things like education and look how you think about a system we have in Ontario where every student is funded equally. But go to United States, they’re funded based on their tax base.”

Ojo-Thompson replies: “What you’re saying is not untrue, but … all I’m saying is that the Jane and Finch kids are not having the same experience as the Forest Hill kids. They’re just not. And that’s despite our equal laws.”

Bilkszto responds by adding: “We have a health-care system here where everyone has access to health care. It is not the same way in the United States. So to sit here and say, in all honesty, we’re talking about facts and figures and to walk into the classroom tomorrow and say Canada is just as bad as the United States, I think we’re doing an incredible disservice to our learners.”

That’s not a help-me-understand question typically posed by workshop participants to trainers. That’s a man saying to a woman, an expert on anti-racism, at the end of a session that is replete with history, data, experience and nuance, that she’s flat-out wrong.

Ojo-Thompson points out a fallacy in his argument. “What I’m finding interesting is that this is in the middle of this COVID disaster, where the inequities in this fair and equal health care system have been properly shown to all of us.”

She then pivots to the principle of the point behind his original challenge of her experience of racism as a Black woman in Canada versus the U.S.

“So we’re here to talk about anti-Black racism, but you in your whiteness think that you can tell me what’s really going on for Black people? Like, is that what you’re doing? Because I think that’s what you’re doing, but I’m not sure. So I’m going to leave you space to tell me what you’re doing right now.”

Anti-racism training sessions are by definition challenging discussions. In every session, Ojo-Thompson references the normalcy of emotions coming up and the importance of accepting them rather than going into flight or freeze defensive postures.

At in-person sessions, defensiveness comes across in the body language, in whether an attendee is participating or avoiding engaging, in whether they choose to cry (you’ll be surprised). You can also tell by the tone of the questions.

Since this was a Zoom session, Ojo-Thompson made a note about that last point. She noted that there were people in the session who were Black, well-informed, well-educated. “Part of this work is listening to Black people,” she says. “Remember, as white people. There’s a whole bunch going on that isn’t your personal experience. … You will never know it to be so. So your job in this work as white people is to believe. And if what you want is clarification, ask for that. Truly. Not with a foot in the: ‘Yeah, but I’m going to tell you how you’re wrong.’ It’s the: ‘Help me understand further, please, because I actually don’t know.’”

She concludes by calling it “a profound and an appropriate teachable moment.”

That was 10 minutes done. Disagreement? Yes. Bullying and harassment? Not seeing it.

At a subsequent meeting the next week, Ojo-Thompson began by revisiting the concept of resistance that she mentioned even before the interaction with Bilkszto and how resistance upholds white supremacy. “I want to open by going back to the concept of resistance,” which “is going to be the most transformational, because we don’t talk enough about the many, many responses to the work, what they look like.”

Soon after she says, “One of the ways that white supremacy is upheld, protected, reproduced, upkept, defended is through resistance.”

Then she references the interaction with Bilkszto from the previous week, saying, “who would have thought my luck would show up so well last week that we got perfect evidence of a wonderful example of resistance that you all got to bear witness to. So we’re going to talk about it, because it doesn’t get better than this.”

This is Ojo-Thompson, doing the hard job of managing a zoom session with 199 people, training leaders on not just the presumptions that lead to discriminations but also how to recognize the resistance to it. This cannot be considered shaming Bilkszto by calling him “a resistor.” Nor is suggesting upholding white supremacy the same as calling someone a white supremacist.

In the previous session, before Bilkszto spoke, Ojo-Thompson had pointed out how one doesn’t even having to be white to uphold white supremacy, that there are “all kinds of kickbacks and rewards” for upholding white supremacy and “you see all kinds of non-white people, for example, attempting to uphold the values of white supremacy, even among Indigenous people, Black people.”

The far-right media ecosystem — organizations and commentators — quickly plumbed the depths of opportunism after Bilkszto ended his life and turned it into an international firestorm.

They martyred Bilkszto to their cause of villainizing diversity, equity and inclusion work and made a target of Ojo-Thompson not just by framing her as a bully but by suggesting her words drove him to suicide. They splashed her face across stories, sometimes multiple times in one story.

The malice spread, and in short order Ontario announced a review of these allegations with a view to “reform professional training.”

On Thursday, the TDSB said it launched an investigation into the circumstances surrounding Bilksztoszto’s death.

Consider this: On the one hand, reams of data that show racism maims and kills. That the system of white supremacy has caused an epidemic of suicides among Indigenous peoples. That the risk of suicide among LGBTQ2+ people is rising.

On the other hand, an isolated tragedy, contentiously linked to a conversation the anti-anti-racists don’t want to have.

Guess which of the two the system comes down on.

If Canadians want to do nothing about our racism, then let’s be open about it. Otherwise, we better believe Black women. Protect Black women.