Liberals reshape judicial bench with appointments of women

2017/05/13 Leave a comment

The Globe finally catches up to the story of the increased diversity of the government’s judicial appointments, almost exclusively focussing on gender with only cursory reference to the increased number of visible minority (8.5 percent) and indigenous (5.1 percent) judicial appointments (after Thursday’s latest batch of appointments).

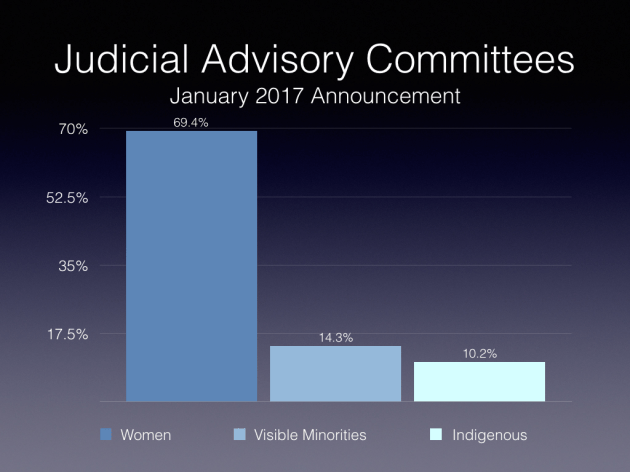

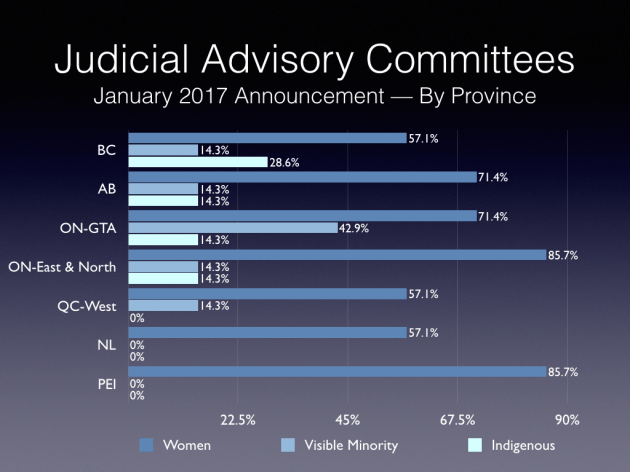

The Globe also misses another key aspect: the increased diversity in the Judicial Appointments Advisory Councils named to date: 62.9 percent women, 11.4 percent visible minorities, and 10.0 percent Indigenous peoples:

The Liberal government is reshaping the bench, appointing a substantial majority of women, even though they make up a minority of applicants. The approach is winning praise from some in the legal community, while sparking concern about “quotas” from others.

A year and a half after taking office, the government has appointed 56 judges, of whom 33 are women – 59 per cent. Yet women make up only 42 per cent of the 795 people who have applied to be judges since the Liberals put in place a new appointment process in October.

Making federal institutions more reflective of Canadian diversity has been a theme of the Liberal government. Its cabinet has an equal number of men and women, and it announced a plan last week to ensure more women and minorities are named to federally funded research chair positions at universities.

Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould says a more diverse bench will build the public’s confidence in the judiciary. “We are beginning to demonstrate how it is possible to have a bench that truly reflects the country we live in,” she said in an e-mail to The Globe and Mail.

But some in the legal community question the government’s commitment to the merit principle in appointing judges to federally appointed courts, which includes the superior courts of provinces, the Federal Court and Tax Court.

“I’m not really in favour of a quota system – those are alarming discrepancies,” Brenda Noble, a veteran family lawyer in Saint John, said in an interview, referring to the gap between female appointees and applicants. “You want to have the best people in the job.”

Ian Holloway, the University of Calgary’s law dean, said it is hard to fault the government for increasing the proportion of women judges. Even so, he said he worries the government is putting too much emphasis on gender.

“In the old days, it was offensive that people got judgeships just because they were Liberals or Tories. That helped breed contempt for the judiciary. What we don’t want to do is replicate that in a different form.”

But others say the government is doing the right thing.

Brenda Hildebrandt, a Saskatoon lawyer and governing member of the Saskatchewan Law Society, was pleased. “Do I think it’s a good thing women are more represented on the bench? Yes, I do, and I would hope that those are qualified candidates and that the fact that they’re women is just one consideration, albeit important.”

Rosemary Cairns Way, a University of Ottawa law professor who has studied diversity on federally appointed courts, supports the government’s move as a way of achieving gender parity. “When there is no shortage of meritorious candidates, it seems to me the government can legitimately choose judges who, in addition to being independently qualified, will fulfill other institutional goals such as a more diverse and gender-balanced bench.”

When the Liberals took office, 35 per cent of the federal judiciary (full-time and semi-retired) were women, according to the Office of the Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs. Given a similar time frame to the Conservatives – a decade in office – the Liberals would ultimately put women in the majority among the full-time federal judiciary if they maintain the current ratio of appointments. The previous government appointed more than 600 full-time federal judges, 30 per cent of them women; women also made up 30 per cent of applicants during the Conservatives’ years in office.

The government’s emphasis on creating a bench more reflective of Canada’s diversity does not extend quite as much to racial minorities as it does to women. However, there are at least seven visible minorities among the new appointees – two of Indigenous ancestry, three of South Asian background, one Japanese-Canadian and one Chinese-Canadian.

The Liberals have authorized the judicial-affairs commissioner to collect, for the first time, data on race, Indigenous status, gender identity, sexual orientation and physical disability of applicants and appointees. But the office would not release those numbers to The Globe and Mail for this story, saying it is still preparing the data and it intends to publish them soon.

The Globe asked Ms. Wilson-Raybould whether she has a numerical target for the appointment of women to the federal judiciary. She replied that the government appoints judges based on merit and the needs of the court. “In assessing merit, I do not discriminate against applicants based on their gender, ethnic or cultural background,” she said in an e-mail.

She acknowledged that the pace of racial-minority appointments is lagging and suggested the problem is a lack of minorities in the legal profession.

“We know that more needs to be done to increase the number of visible minorities in our law schools. As that happens, the face of the profession will change and evolve to better reflect the rest of the population.”

Rob Nicholson, a former Conservative justice minister, and the party’s current justice critic, said his chief concern is that qualified people be appointed. “If it’s 55-per-cent women and 45-per-cent men, as long as we get qualified people for this,” he said.

Source: Liberals reshape judicial bench with appointments of women – The Globe and Mail