Blow: The Impact of the Browning of America on Anti-Blackness

2021/11/16 1 Comment

Likely similar in Canada:

One of the things I often hear as a person who frequently writes about race, ethnicity and equality, is that the browning of America — the coming shift of the country from mostly white to mostly nonwhite — is one of the greatest hopes in the fight against white supremacy and oppression.

But this argument always flies too high to pay attention to the details on the ground. For me, white supremacy is only one foot of the beast. The other is anti-blackness. You have to fight both.

The sad reality is, however, that anti-blackness — or anti-darkness, to remove the stricture of a single-race definition for the sake of this discussion — exists in societies around the world, including nonwhite ones.

In too many societies across the globe, where a difference in skin tone exists, the darker people are often assigned a lower caste.

And, when people migrate to this country from those societies, they can bring those biases with them, underscoring that you don’t have to be white to contribute to anti-blackness.

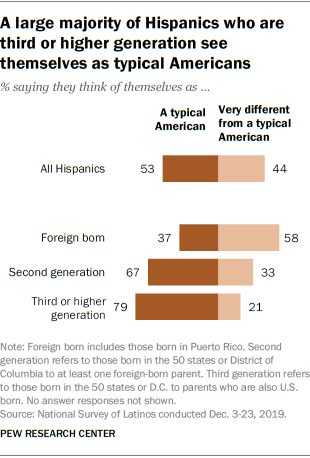

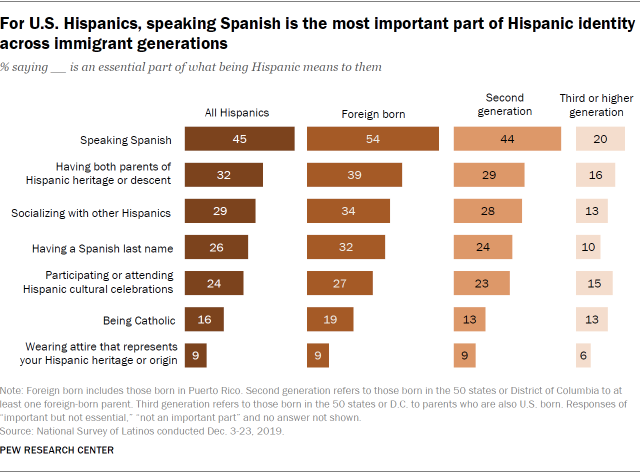

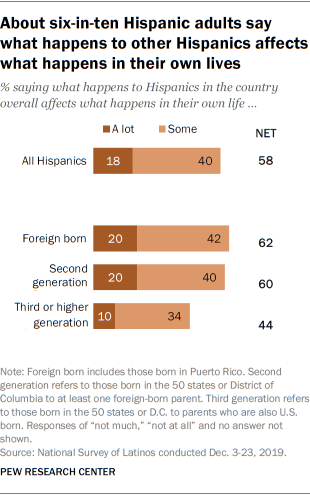

A fascinating report issued this month by the Pew Research Center explored colorism in the Hispanic community and underscored how anti-blackness, or anti-darkness, is no respecter of race or ethnicity. It is pervasive and portends a future in which the browning of America does not succeed in wiping away its racial prejudices.

First, the report reaffirmed what we all know to be true: A majority of Hispanic adults, regardless of skin tone, report experiencing discrimination.

But dark-skinned Hispanics reported far more discrimination than light-skinned ones.

The survey allowed Hispanics to select the skin tone closest to their own on a 10-point scale. Eighty percent of respondents chose the four lightest tones, which the report identified as light-skinned, but only 15 percent chose the six darker skin tones, which the report identified as dark-skinned. Others chose not to answer.

The survey found that:

“A majority (62 percent) of Hispanic adults say having a darker skin color hurts Hispanics’ ability to get ahead in the United States today at least a little. A similar share (59 percent) say having a lighter skin color helps Hispanics get ahead. And 57 percent say skin color shapes their daily life experiences a lot or some, with about half saying discrimination based on race or skin color is a “very big problem” in the U.S. today.”

Intolerance wasn’t only coming from outside the Hispanic community, but also from within it. Nearly half of the Hispanic adults surveyed said that they have often or sometimes heard a Hispanic friend or family member make comments or jokes about other Hispanics and about non-Hispanics “that might be considered racist or racially insensitive.” Dark-skinned Hispanics reported these incidents at a higher rate than light-skinned Hispanics.

When it came to how much attention was paid to racial issues in this country, a majority of Hispanics, understandably, said too little attention is paid to race and racial issues concerning Hispanics. A plurality also said that too little attention is paid to race and racial issues nationally.

But a plurality said too much attention was paid to issues concerning Black people.

This is troubling. Concern over racial issues isn’t a zero-sum game. There should be more concern for all groups and less of a belief that some are receiving too little and others too much.

These issues around how darker-skinned people of all races and ethnicities are perceived and treated must be addressed. This is in part because we are racing toward a future in which the share of minorities who are dark-skinned will only be a fraction.

By 2065, it is projected that not only will Asian Americans outnumber African Americans, but there will also be nearly twice as many Hispanics in the country as Black people.

As I have mentioned before, I worry that white supremacy could be replaced with a light supremacy, a society in which light-skinned people are still advantaged and dark-skinned people are still oppressed, even as the white majority recedes.

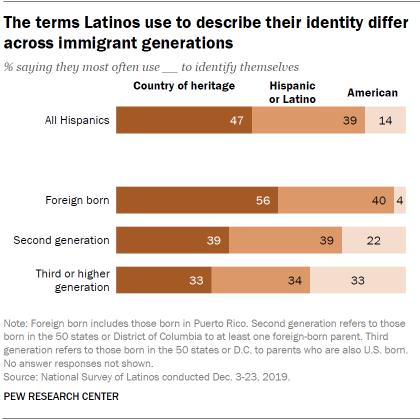

Interestingly, in the Pew report, respondents who identified as Hispanic, Latino or of Spanish origin were asked their race and told that for the purposes of the race question, “Hispanic origins are not races.” They could pick more than one race. According to the report, 58 percent identified as white. (Actual census datafound that dramatically fewer identified as white.)

I have seen some encouraging allyship between Black and brown people in my lifetime. Just last year, following the murder of George Floyd, a Pew survey found that an even higher percentage of Hispanics than Black people said that they had participated in protests.

But these groups have different histories with oppression in this country and different ongoing relationships with it. Pew found in 2015 that “immigration since 1965 has swelled the nation’s foreign-born population from 9.6 million then to a record 45 million.” The vast majority of that growth obviously happened after the Civil Rights Movement.

We must all recognize these differences and confront them in honest and deliberate ways. Colorism and racism are cousins, and both are a pestilence.

Source: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/14/opinion/latinos-colorism-anti-blackness.html