Les francophones quasiment absents des postes clés de la diplomatie canadienne

2020/12/15 Leave a comment

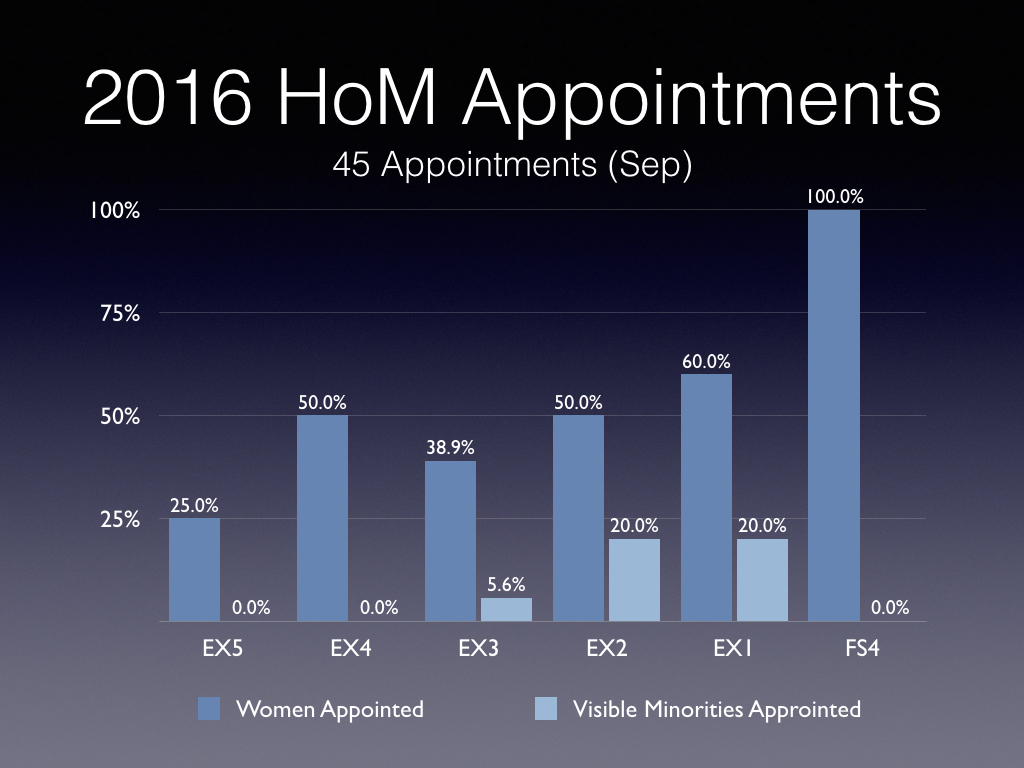

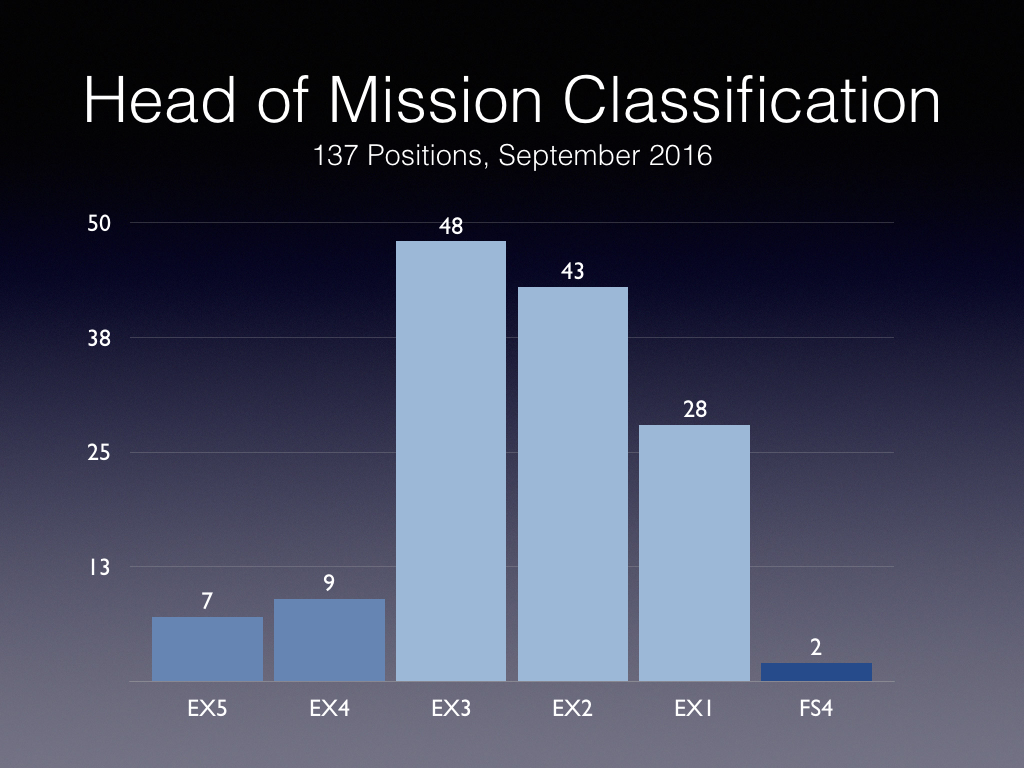

While I focus more on visible minority representation, did a quick check of the head of mission data that I keep which confirms their concerns (the government over the past five years has improved representation of women and visible minorities in head of mission appointments):

L’ère des influents diplomates francophones au sein du réseau diplomatique canadien est révolue. Presque uniquement composée d’anglophones, la haute direction d’Affaires mondiales Canada ne fait accéder que d’autres anglophones aux postes stratégiques, forçant au passage bien des francophones ambitieux à faire carrière dans leur langue seconde.

Le Devoir s’est entretenu avec une dizaine d’employés d’expérience, cadres et ex-cadres d’Affaires mondiales Canada, dont un ambassadeur en fonction. Tous sont d’avis que l’absence de francophones aux postes clés de la diplomatie canadienne est très préoccupante. Plusieurs d’entre eux dénoncent un climat d’indifférence face au français qui s’est amplifié avec le temps, malgré les espoirs suscités par l’entrée en fonction du ministreFrançois-Philippe Champagne, lui-même francophone. Son bureau n’a pas directement réagi aux questions du Devoir, laissant la rédaction d’une réponse aux bons soins de ses fonctionnaires. Ils confirment « certains défis au niveau des cadres supérieurs », alors même qu’un grand nombre des employés du ministère sont francophones.

Tout en haut de la pyramide, les quatre sous-ministres qui dirigent l’institution fédérale sont tous anglophones, comme 11 des 12 sous-ministres adjoints des prestigieux secteurs « géographique » et « fonctionnel ». Tous secteurs confondus, les quelques sous-ministres adjoints francophones occupent les postes les moins stratégiques pour les affaires extérieures, comme les ressources humaines ou l’administration, selon une analyse de l’organigramme obtenu par Le Devoir, confirmée par des sources au sein de l’organisation. En plus, parmi les 15 sièges de directeurs généraux, patrons des ambassadeurs, seulement deux sont occupés par des francophones, dont le responsable d’Affaires panafricaines, qui n’a pas d’ambassade sous sa responsabilité.

« Affaires mondiales Canada est l’un des ministères les plus francophones de la machine fédérale, mais ça ne se traduit absolument pas au niveau supérieur. C’est un peu comme si on était dans les années 1950 : tout le monde sur le plancher de la manufacture est francophone et, au niveau des contremaîtres, tout le monde est anglophone », témoigne un employé haut placé d’une ambassade canadienne qui a requis l’anonymat puisqu’il n’est pas autorisé à parler publiquement de cette question.

« Je ne peux même pas vous nommer un francophone et dire “cette personne-là a de l’influence”. »

La dernière francophone à occuper un poste stratégique dans la haute direction des Affaires étrangères fut Isabelle Bérard, ex-cheffe de la branche Afrique subsaharienne. Elle a été remplacée en 2020 par une haute fonctionnaire anglophone ayant fait carrière dans d’autres ministères et qui n’a aucune expérience en diplomatie.

« La langue, c’est important, mais la compétence est importante aussi. Si vous ne connaissez rien à l’Afrique et vous êtes nommée sous-ministre adjointe à l’Afrique… À mon avis, c’est un sacré problème », a commenté Jocelyn Coulon, qui a été conseiller politique de l’ancien ministre des Affaires étrangères Stéphane Dion.

Sommet de la pyramide

Si le gouvernement ne nomme que des anglophones dans les postes de haute gestion les plus importants, ce n’est pas faute de relève francophone au sein de l’organisation. Selon un courriel datant de 2019 obtenu par Le Devoir qui recense le nombre de cadres d’Affaires mondiales Canada pour chacune des langues officielles, les francophones représentent une grande part des gestionnaires de premier et de second niveau (EX1 et EX2), à environ 30 %. Au fur et à mesure que l’on monte les échelons, toutefois, leur nombre s’amenuise, à approximativement 1 gestionnaire sur 8 aux hauts niveaux (EX4 et EX5). Des données plus récentes, mais moins précises, fournies par Affaires mondiales Canada confirment que les francophones sont plus nombreux à rester au bas de la pyramide.

« La haute gestion est anglophone et a de la difficulté à lire ou écrire en français. C’est presque impossible de monter au sein du ministère à un poste de haute gestion », témoigne un ex-cadre francophone d’Affaires mondiales Canada qui ne souhaite pas être nommé, par crainte de répercussions pour non-respect d’une entente de confidentialité.

Tous les cadres et ex-cadres consultés s’entendent pour dire que, même si de nombreux anglophones parlent un excellent français à Affaires mondiales Canada, les exigences linguistiques pour les anglophones permettent même à ceux qui maîtrisent très mal la langue de Molière d’accéder à la haute direction, alors qu’une faiblesse en anglais écrit est susceptible de bloquer la carrière de francophones. Pourtant, l’article 39 de la Loi sur les langues officielles garantit les mêmes possibilités d’avancement pour les fonctionnaires des deux groupes linguistiques.

« Je ne dirais pas qu’il n’y a pas de cadres supérieurs francophones, mais de plus en plus, ils sont ghettoïsés dans des fonctions, pas sans importance, mais corporatives. Et c’est la même chose pour les ambassadeurs. Les francophones sont en voie de disparition au niveau des postes à l’étranger », se désole un ambassadeur qui a requis l’anonymat pour parler librement de cette question.

Nostalgique, le diplomate posté à l’étranger se désole de la fin d’une époque où des Canadiens francophones s’illustraient sur la scène mondiale, comme au début des années 2000, avec Claude Laverdure comme ambassadeur de France, Marc Lortie en Espagne, Joseph Caron en Chine ou encore Gaëtan Lavertu au Mexique, pour ne nommer que ceux-là. Excluant les « nominations politiques » de Stéphane Dion en Allemagne et d’Isabelle Hudon en France, ainsi que deux postes vacants, aucun diplomate francophone de carrière n’est ambassadeur dans un pays du G20 en ce moment, témoignent les profils des chefs de mission en poste.

Selon plusieurs sources, certains ambassadeurs canadiens à l’étranger ne parlent pas du tout français. « De plus en plus, nos ambassadeurs ne sont pas capables de s’exprimer en français, confirme Pierre Alarie, ex-ambassadeur du Mexique à la retraite depuis 2019. Je ne comprends pas que, dans un pays de 38 millions de personnes, on n’est pas capables de trouver 175 chefs de mission bilingues. »

Lente érosion

« Il y a eu une érosion ces dernières années. On a perdu une sensibilité au français, croit Guy Saint-Jacques, ex-ambassadeur canadien en Chine, jusqu’en 2006. C’est très préoccupant. Le ministère est le visage du Canada à l’étranger. Si on n’a plus de français, c’est un problème. »

Il précise toutefois que la langue de Molière est malmenée depuis longtemps aux Affaires étrangères. Lui-même témoigne avoir tenté d’obtenir une promotion dans les années 1990 devant un jury tout anglophone, dont un membre ne parlait pas français. Plusieurs sources indiquent que cette situation se produit encore de nos jours.

« Le français s’est émietté d’unefaçon progressive, en même temps que les sous-ministres sont devenus des gestionnaires et le pouvoir du bureau du premier ministre s’est accru », confirme l’ex-ambassadeur Ferry de Kerckhove, en poste jusqu’en 2011. Selon lui, l’incorporation du Commerce extérieur aux Affaires étrangères, dans les années 1980, puis plus récemment la fusion de l’Agence canadienne de développement international (ACDI), en 2013, ont provoqué une centralisation du pouvoir qui a fait globalement diminuer l’influence des francophones dans la diplomatie canadienne.

Basée à Gatineau, l’ACDI était réputée comme étant la chasse gardée des francophones. L’institution a été engloutie par la mégastructure actuelle qui chapeaute trois ministères, renommée Affaires mondiales Canada par Justin Trudeau en 2015.

« On s’est privés de beaucoup d’expertise francophone », analyse Isabelle Roy, ex-ambassadrice retraitée depuis le début de l’année et spécialiste de l’Afrique. Selon elle, la tendance à l’anglicisation des hautes sphères diplomatique a des conséquencessur la manière dont le Canada pratique sa diplomatie. Plusieurs autres ex-ambassadeurs se désolent aussi de la perte du point de vue francophone dans la façon dont le Canada interagit avec le monde. « Ça creuse le sillon d’une sensibilité accrue envers certains pays, et une sensibilité déficiente pour d’autres pays », conclut Mme Roy.

Faire carrière en anglais

Faute de francophones dans la haute direction, de nombreux fonctionnaires du réseau diplomatique font le choix de mener leur vie professionnelle uniquement en anglais, confirment lesemployés et ex-employés interrogés.

« Faire carrière [en politique étrangère], pour un francophone, veut dire faire carrière en anglais. Si on veut faire carrière en français, c’est se cantonner dans des fonctions corporatives. Ça ne sera pas en politique étrangère comme telle », affirme un employé d’Affaires mondiales comptant 20 ans de carrière et ayant requis l’anonymat puisqu’il n’a pas l’autorisation de parler aux médias.

Les ambassadeurs et ex-ambassadeurs interrogés ont tous dressé le portrait d’une administration qui n’oblige pas explicitement l’utilisation de l’anglais dans les communications, mais qui instaure un climat dans lequel un travail sera ignoré des patrons s’il est rédigé dans la langue de Molière.

« Pour ce qui est des réunions, on nous réitère toujours qu’on est libres de parler la langue de notre choix. Mais surtout pour les réunions de haut niveau, c’est presque être le trouble-fête si on insiste à [vouloir] s’exprimer en français, parce qu’on sait qu’il y a des hauts gestionnaires qui ne maîtrisent pas le français, même s’ils ont peut-être le niveau C [niveau de compétence requis pour certains postes] », témoigne un ambassadeur actuellement en poste à l’étranger.

Affaires mondiales Canada confirme qu’une grande part de ses employés (42 %) sont francophones, un taux qui chute à 18 % chez les hauts cadres, selon son calcul. « Le ministère reconnaît qu’il existe certains défis au niveau des cadres supérieurs et cela fait partie des stratégies mises en place dans notre Plan d’action pour les langues officielles 2019-2022 », explique la porte-parole d’Affaires mondiales Canada, Ciara Trudeau, par courriel.

Dans sa réponse fournie au Devoir, le gouvernement précise qu’il met en avant le caractère bilingue du Canada en guise d’exemple d’une société ouverte à la diversité linguistique auprès des autres pays.

Source: Les francophones quasiment absents des postes clés de la diplomatie canadienne