Multiculturalism and related posts of interest

2018/04/28 Leave a comment

Last of my ‘catch-up’ series.

Starting with the Environics Institute’ Canada’s World Survey, which highlights the degree to which Canada has a more open and inclusive approach than most other countries, as highlighted in the Executive Summary:

Canadians’ views on global issues and Canada’s role in the world have remained notably stable over the past decade.

In the decade following the first Canada’s World Survey (conducted early in 2008), the world experienced significant events that changed the complexity and direction of international affairs: beginning with the financial meltdown and ensuing great recession in much of the world, followed by the continued rise of Asia as an emerging economic and political centre of power, the expansion of global terrorism, increasing tensions with North Korea and risks of nuclear conflagration; and a growing anti-government populism in Western democracies. Despite such developments, Canadians’ orientation to many world issues and the role they see their country playing on the international stage have remained remarkably stable over the past decade. Whether it is their perception of top issues facing the world, concerns about global issues, or their views on the direction the world is heading, Canadians’ perspectives on what’s going on in the world have held largely steady.

As in 2008, Canadians have maintained a consistent level of connection to the world through their engagement in international events and issues, their personal ties to people and cultures in other countries, frequency and nature of their travel abroad, and financial contributions to international organizations and friends and family members abroad. And Canadians continue to view their country as a positive and influential force in the world, one that can serve as a role model for other countries.

This consistency notwithstanding, Canadians have been sensitive to the ebb and flow of intenational events and global trends.

While Canadians’ perspectives on many issues have held steady over the past decade, there have also been some shifts in how they see what’s going on in the world and how they perceive Canada’s role on the global stage, in response to key global events and issues. This suggests Canadians are paying attention to what happens beyond their own borders, and that Canadian public opinion is responsive to media coverage of the global stage.

Canadians today are more concerned than a decade ago about such world issues as terrorism, the spread of nuclear weapons, and global migration/refugees. And the public has adjusted its perceptions of specific countries as having a positive (e.g., Germany) or negative (e.g., North Korea, Russia) impact in the world today. Canadians are also shifting their opinions about their country’s influence in world affairs, placing stronger emphasis on multiculturalism and accepting refugees, our country’s global political influence and diplomacy, and the popularity of our Prime Minister.

Canadians increasingly define their country’s place in the world as one that welcomes people from elsewhere.

Multiculturalism, diversity and inclusion are increasingly seen by Canadians as their country’s most notable contribution to the world. It is now less about peacekeeping and foreign aid, and more about who we are now becoming as a people and how we get along with each other. Multiculturalism and the acceptance of immigrants and refugees now stand out as the best way Canadians feel their country can be a role model for others, and as a way to exert influence on the global stage.

Moreover, Canadians are paying greater attention to issues related to immigration and refugees than they did a decade ago, their top interest in traveling abroad remains learning about another culture and language; and they increasingly believe that having Canadians living abroad is a good thing, because it helps spread Canadian culture and values (which include diversity) beyond our shores. Significantly, one in three Canadians report a connection to the Syrian refugee sponsorship program over the past two years, either through their own personal involvement in sponsoring a refugee family (7%) or knowing someone who has (25%).

Young Canadians’ views and perspectives on many aspects of world affairs have converged with those of older cohorts, but their opinions on Canada’s role on the world stage have become more distinct when it comes to promoting diversity.

It is young Canadians (ages 18 to 24) whose level of engagement with world issues and events has evolved most noticeably over the past decade, converging with their older counterparts whose level of engagement has either not changed nor kept pace with Canadian youth. Young people are increasingly following international issues and events to the same degree, they are as optimistic about the direction of the world as older Canadians, and they are close to being as active as travelers. At the same time, Canadian youth now hold more distinct opinions on their country’s role in the world as it relates specifically to diversity. They continue to be the most likely of all age groups to believe Canada’s role in the world has grown over the past 20 years, and are now more likely to single out multiculturalism and accepting immigrants/refugees as their country’s most positive contribution to the world.

Foreign-born Canadians have grown more engaged and connected to world affairs than native-born Canadians, and are more likely to see Canada playing an influential role on the global stage.

Foreign-born Canadians have become more involved in what’s going on outside our borders over the past decade, opening a noticeable gap with their native-born counterparts. They continue to follow international news and events more closely than people born in Canada, but have developed a much greater concern for a range of issues since 2008, while native-born Canadians’ views have not kept pace. Canadians born elsewhere have grown more optimistic about the direction in which the world is heading, while those born in the country have turned more pessimistic. And Canadians born in other countries have also become more positive about the degree of influence Canada has on world affairs, and the impact the country can have on addressing a number of key global issues.

Source: Canada’s World Survey 2018 – Executive Summary, Canadians believe multiculturalism is country’s key global contribution: study

Some other stories that I found of interest:

The very different pictures of how well integration is working for visible minority and immigrant women between Status of Women Canada (overly negative) and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (not enough granularity between different visible minority groups, captured by Douglas Todd: Secret immigration report exposes ‘distortions’ about women .

Todd continues with some of his interesting exploration immigration issues, including regarding different communities (Douglas Todd: Canadian Hindus struggling with Sikh activism) and highlighting the work of Eric Kaufmann (Douglas Todd: Reducing immigration to protect culture not seen as racist by most) who, in my view, overstates “white flight” and related ethno-cultural tensions and has an overly static view of society.

Timothy Caulfield asks the questionIs direct-to-consumer genetic testing reifying race?:

From a genetic point of view, all humans are remarkably similar. Indeed, when the Human Genome Project was completed in 2003, it was confirmed that the “3 billion base pairs of genetic letters in humans [are] 99.9 percent identical in every person.” There are, of course, genetic differences that occur more frequently in certain populations — lactose intolerance, for example, is more common in people from East Asia. But there is simply no reason to think that your genes tell you something significant about your cultural heritage. There isn’t a lederhosen gene.

More important, we shouldn’t forget that the concept of “race” is a biological fiction. The crude racial categories that we use today — black, white, Asian, etc. — were first formulated in 1735 by the Swedish scientist and master classifier, Carl Linnaeus. While his categories have remained remarkable resilient to scientific debunking, there is almost universal agreement within the science community that they are biologically meaningless. They are, as is often stated, social constructs.

To be fair, DTC ancestry companies do not use racial terminology, though phrases like “DNA tribe” feel close. But as research I did with Christen Rachul and Colin Ouellette demonstrates, whenever biology is attached to a rough human classification system (ancestry, ethnicity, etc.), the public, researchers and the media almost always gravitate back to the concept of race. In other words, the more we suggest that biological differences between groups matter — and that is exactly what these companies are suggesting — the more the archaic concept of race is perceived, at least by some, as being legitimate. A 2014 study supports this concern. The researchers found that the messaging surrounding DTC ancestry testing reifies race as a biological reality and may, for example, “increase beliefs that whites and blacks are essentially different.” The authors go on to conclude that: “The results suggest that an unintended consequence of the genomic revolution may be to reinvigorate age-old beliefs in essential racial differences.”

Other research has found that an emphasis on genetic difference has the potential to (no surprise here) increase the likelihood of racist perspectives and decrease the perceived acceptability of policies aimed at addressing prejudice.

Some less-than-progressively-minded groups have already turned to ancestry testing as a way to prove their racial purity. White supremacists in the United States, for example, have embraced these services — often with ironic and pretty hilarious results (surprise, you’re not of pure “Aryan stock”!).

But I am sure most of the people who use ancestry companies are not thinking about racial purity, the reification of race or antiracism policies when they order their tests. And I understand that these tests are, for the vast majority of customers, providing what is essentially a bit of recreational science. In fact, I’ve had my ancestry mapped by 23andMe (I am, if you believe the results, almost 100 percent Irish — hence my love of Guinness). It was a fun process. Still, as the research suggests, the messaging surrounding this industry has the potential to facilitate the spread and perpetuation of scientifically inaccurate and socially harmful ideas about difference. In this era of heightened nationalism and populist exceptionalism, this seems the last thing we need right now.

So, don’t believe the marketing. Your genes are only part of the infinitely complex puzzle that makes “you uniquely you.” If you feel a special connection to lederhosen, rock the lederhosen. No genes required.

Lack of diversity in highlighted is sectors as varied as entertainment (The Billion-Dollar Romance Fiction Industry Has A Diversity Problem) and education (Lack of diversity persists among teaching staff at Canadian universities, colleges, report finds). Chris Selley: Granting Sikh bikers ‘right’ to ride without helmets only adds to religious freedom confusion provides a good critical take on whether religious freedom extends to riding motorcycles (Ontario does not allow, British Columbia and Alberta do).

Kim Thúy on how ‘refugee literature’ differs from immigrant literature provides an interesting perspective:

“Refugee and immigrant are very different,” she says in an interview. “A refugee is someone ejected from his or her past, who has no future, whose present is totally empty of meaning. In a refugee camp, you live outside of time—you don’t know when you’re going to eat, let alone when you’re going to get out of there. And you’re also outside of space because the camp is no man’s land. To be a human being you have to be part of something. The first time that we got an official piece of paper from Canada, my whole family stared at it—until then, we were stateless, part of nothing.”

Letters from Japanese-Canadian teenagers recount life after being exiled from B.C. coast enriches our understanding of the impact of their uprooting and exile under Japanese wartime internment (similar to Obasan):

“I don’t know of any other archival collections that are like this,” she said. “They might exist, but I don’t know of any. The combination of young people’s letters and letters to a non-Japanese Canadian person is just incredible to me. This is really special.

“One of the things I love about them is that they’re so clearly ordinary people. I think sometimes when the story gets told, that gets missed — that these are teenagers who are bored, and curious. It’s just really touching.”

And a variety of interesting articles on Islam and Muslims: Why so many Turks are losing faith in Islam, Can Muslim Feminism Find a Third Way? Ursula Lindsey and Gender parity in Muslim-majority countries: all is not bleak: Sheema Khan.

One of the most interesting is The Conversion/Deconversion Wars: Islam and Christianity using Pew Research data to assess respective trends:

It turns out that (American) Islam is losing Muslims at a pretty high rate. About a quarter of adults raised Muslim deconvert.

The problem is, from a secularist’s point of view, is that just as many convert to the religion. It has a high conversion rate, especially when compared to Christianity. Islam is growing by about 100,000 per year.

Per Research recently released a report that said:

“Like Americans in many other religious groups, a substantial share of adults who were raised Muslim no longer identify as members of the faith. But, unlike some other faiths, Islam gains about as many converts as it loses.

About a quarter of adults who were raised Muslim (23%) no longer identify as members of the faith, roughly on par with the share of Americans who were raised Christian and no longer identify with Christianity (22%), according to a new analysis of the 2014 Religious Landscape Study. But while the share of American Muslim adults who are converts to Islam also is about one-quarter (23%), a much smaller share of current Christians (6%) are converts. In other words, Christianity as a whole loses more people than it gains from religious switching (conversions in both directions) in the U.S., while the net effect on Islam in America is a wash.

A 2017 Pew Research Center survey of U.S. Muslims, using slightly different questions than the 2014 survey, found a similar estimate (24%) of the share of those who were raised Muslim but have left Islam. Among this group, 55% no longer identify with any religion, according to the 2017 survey. Fewer identify as Christian (22%), and an additional one-in-five (21%) identify with a wide variety of smaller groups, including faiths such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Judaism, or as generally “spiritual.”

The same 2017 survey asked converts fromIslam to explain, in their own words, their reasons for leaving the faith. A quarter cited issues with religion and faith in general, saying that they dislike organized religion (12%), that they do not believe in God (8%), or that they are just not religious (5%). And roughly one-in-five cited a reason specific to their experience with Islam, such as being raised Muslim but never connecting with the faith (9%) or disagreeing with the teachings (7%) of Islam. Similar shares listed reasons related to a preference for other religions or philosophies (16%) and personal growth experiences (14%), such as becoming more educated or maturing.”

There is perhaps an interesting explanation for some of this deconversion data:

“One striking difference between former Muslims and those who have always been Muslim is in the share who hail from Iran. Those who have left Islam are more likely to be immigrants from Iran (22%) than those who have not switched faiths (8%). The large number of Iranian American former Muslims is the result of a spike in immigration from Iran following the Iranian Revolution of 1978 and 1979 – which included many secular Iranians seeking political refuge from the new theocratic regime.”

How does this compare to people who converted to Islam?

“Among those who have converted to Islam, a majority come from a Christian background. In fact, about half of all converts to Islam (53%) identified as Protestant before converting; another 20% were Catholic. And roughly one-in-five (19%) volunteered that they had no religion before converting to Islam, while smaller shares switched from Orthodox Christianity, Buddhism, Judaism or some other religion.

When asked to specify why they became Muslim, converts give a variety of reasons. About a quarter say they preferred the beliefs or teachings of Islam to those of their prior religion, while 21% say they read religious texts or studied Islam before making the decision to switch. Still others said they wanted to belong to a community (10%), that marriage or a relationship was the prime motivator (9%), that they were introduced to the faith by a friend, or that they were following a public leader (9%).”

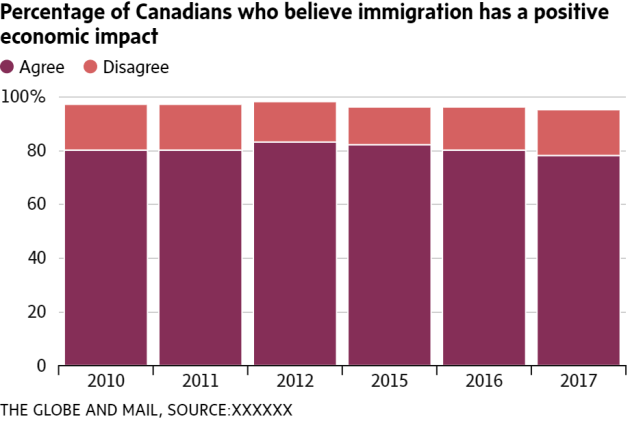

As debates rage through much of the developed world over whether to close doors to newcomers, Canadian attitudes toward immigration remain positive.

As debates rage through much of the developed world over whether to close doors to newcomers, Canadian attitudes toward immigration remain positive.