Yakabuski: Le Canada, champion mondial d’immigration

2022/10/31 Leave a comment

Good observations on the contrast between Quebec and the rest of Canada:

Le ministre fédéral de l’Immigration, des Réfugiés et de la Citoyenneté, Sean Fraser, s’apprête à dévoiler de nouvelles cibles en matière d’immigration pour 2023, 2024 et 2025. Et tout indique que l’annonce que M. Fraser fera mardi prochain prévoira une nouvelle hausse du nombre de résidents permanents par rapport aux dernières cibles, celles-là annoncées il y a un an à peine. Alors que le Québec promet de plafonner ses seuils d’immigration autour de 50 000 nouveaux résidents permanents par année, le reste du Canada, lui, s’apprêterait à bientôt accueillir plus de huit fois ce nombre. Nul besoin d’être économiste ou démographe pour anticiper les conséquences à court et à long termes de ces positions discordantes.

Déjà, le Québec voit sa part d’immigrants fondre comme peau de chagrin d’année en année. Destination de 19,2 % des immigrants arrivés au Canada entre 2006 et 2011, le Québec n’accueillait plus que 15,3 % des immigrants entrés au pays entre 2016 et 2021. Les données provenant du dernier recensement publiées cette semaine par Statistique Canada témoignent de l’énorme transformation démographique que connaît le Canada anglais, et ce, même en dehors de ses plus grandes métropoles.

À Hamilton et à Winnipeg, deux villes ayant une population semblable à celle de Québec, la proportion d’immigrants s’élève maintenant à plus de 25 % ; dans la Vieille Capitale, à peine 6,7 % des résidents sont nés en dehors du Canada. Dans la ville de Saguenay, une proportion famélique de la population est issue de l’immigration, soit 1,3 %, alors qu’à Red Deer et à Lethbridge, des villes albertaines de tailles semblables, les proportions sont de 16,9 % et de 14,4 %, respectivement.

Les chiffres frappent encore davantage l’imagination lorsque l’on tient compte des enfants des immigrants. Dans la grande région de Toronto, par exemple, presque 80 % des résidents sont immigrants de première ou de deuxième générations, selon une analyse des données du recensement effectuée par le démographe Doug Norris, de la firme torontoise Environics. À Montréal, environ 46 % des résidents sont immigrants ou enfants d’immigrants. Bien qu’il s’agisse d’une proportion passablement élevée, c’est moins qu’à Vancouver (73 %), qu’à Calgary (55 %) ou qu’à Edmonton (50 %).

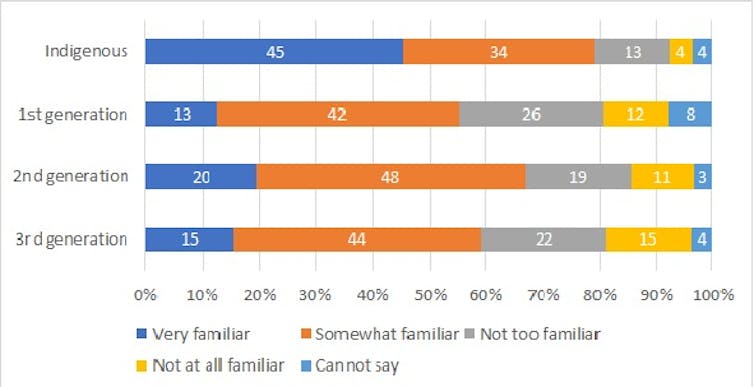

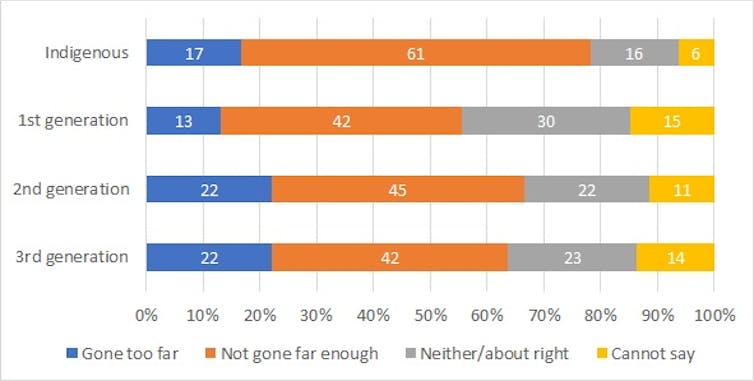

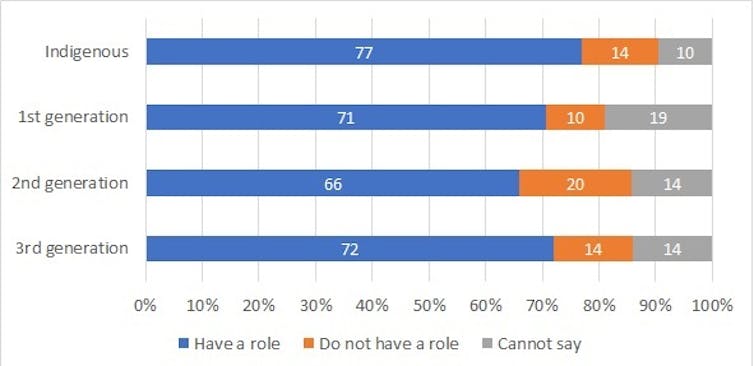

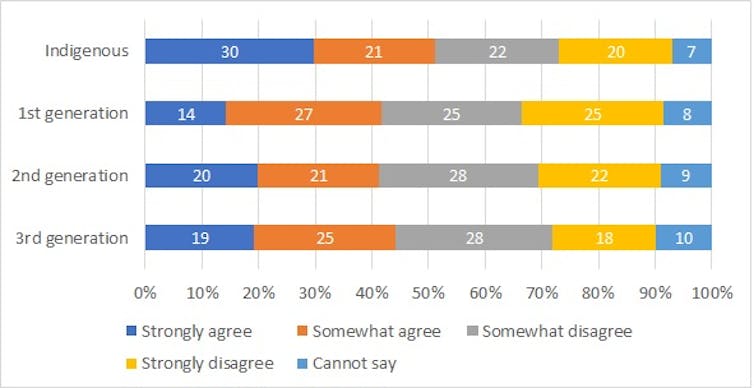

Selon les résultats d’un sondage publié cette semaine par Environics, et effectué pour le compte de L’Initiative du siècle, les Canadiens sont plus favorables que jamais à l’immigration. Ceci n’est pas surprenant ; plus de 40 % des Canadiens sont immigrants ou enfants d’immigrants. On peut s’attendre à ce que ces gens aient un parti pris en faveur de l’immigration.

Mais le consensus canadien en matière d’immigration s’étend bien au-delà des communautés culturelles du pays. « Alors même que le pays accueille plus de 400 000 nouveaux arrivants par année, sept Canadiens sur dix soutiennent les seuils actuels d’immigration — la plus forte majorité en 45 ans de sondages Environics, a fait remarquer Lisa Lalande, présidente de L’Initiative du siècle, un organisme qui prône une politique d’immigration ayant pour but d’augmenter la population canadienne à 100 millions de personnes en l’an 2100. Malgré la rhétorique chargée sur l’immigration durant la campagne électorale provinciale, les Québécois appuient tout autant l’accueil des immigrants et des réfugiés que les Canadiens ailleurs au pays. »

Or, le sondage d’Environics fut mené en septembre, alors que la Coalition avenir Québec (CAQ) promettait de maintenir les seuils d’immigration à 50 000 dans la province. Donc, l’expression « les seuils actuels d’immigration » n’a pas le même sens ici qu’ailleurs au Canada. Au Québec, ces seuils sont plutôt modestes ; dans le reste du Canada, ils sont très élevés.

Les 50 000 résidents permanents que le Québec s’engage à accueillir chaque année équivalent à environ 0,6 % de la population, et cette proportion est appelée à diminuer au fur et à mesure que la population augmentera. Les seuils d’immigration ailleurs au Canada s’élèvent à environ 1,2 % de la population par année, alors que cette population augmente à un rythme beaucoup plus rapide qu’au Québec. Au lieu de 400 000 nouveaux arrivants par an, c’est près de 500 000 immigrants que le reste du Canada pourrait bientôt en accueillir. Et des voix s’élèvent pour qu’Ottawa fasse preuve d’encore plus d’ambition en matière d’immigration.

« Bien que les chiffres absolus semblent élevés, ils doivent en fait être plus élevés encore en raison des défis démographiques du Canada, ont insisté pour dire l’ex-ministre libéral de l’Innovation, Navdeep Bains, et son ancien chef de cabinet, Elder Marques, dans un article publié la semaine dernière dans le National Post. Au début du XXe siècle, un Canada beaucoup plus petit accueillait autant d’immigrants que le Canada le fait aujourd’hui… Un Canada plus grand, plus riche et plus outillé nous attend si nous sommes prêts à faire le saut. »