Seeing more articles advocating for a population policy, which of course would become the base for immigration levels, permanent and temporary. Of course, the experience of most countries that have tried to increase birth rates has been mixed at best, with few successful efforts:

…How quickly should Canada be growing?

Historically, annual immigration targets were set by cabinet based largely on a political judgment. After consulting with others, including the provinces, this was meant to be a sort of prudential assessment of what Canada can accommodate and what Canadians might accept. Up until recently, this assessment appears to have performed reasonably well. Yet in light of recent events, it might be prudent to return to my basic point—that the Canadian government should set out to establish a well-defined population policy—and perhaps in so doing, be somewhat more formulaic in its approach to immigration.

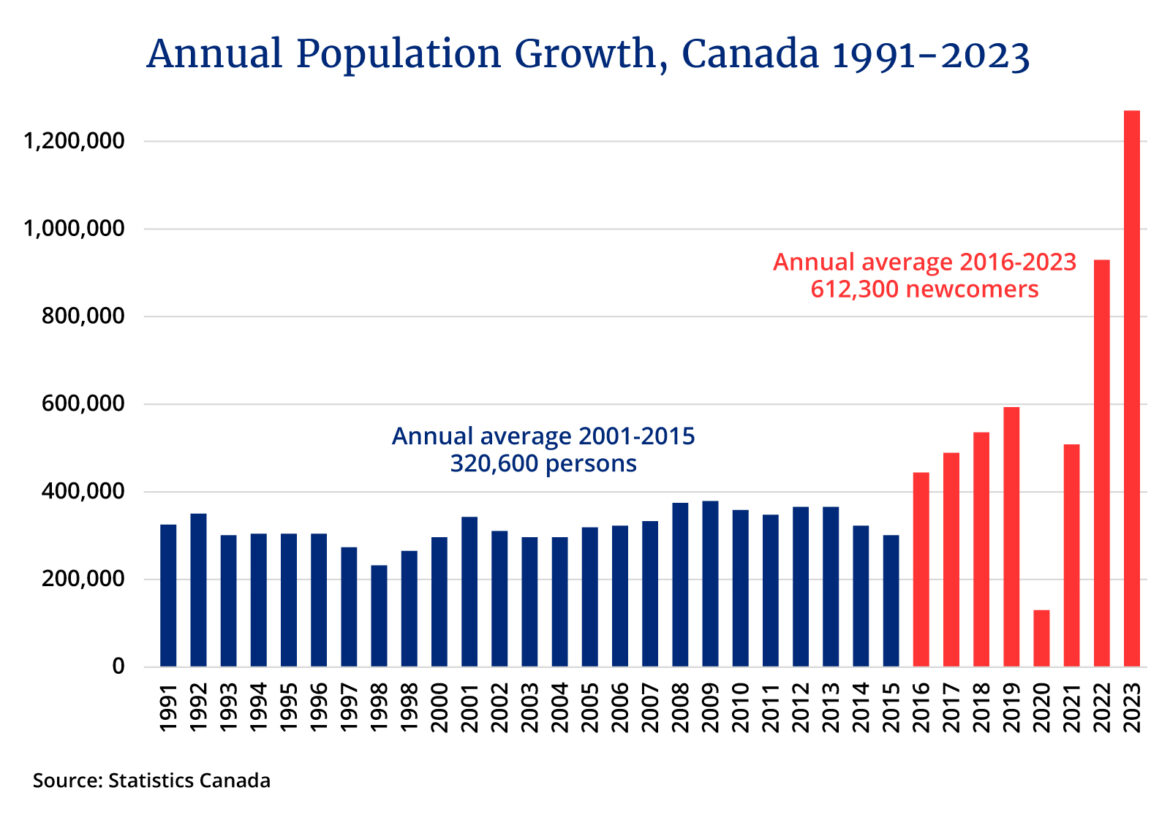

The first order of business would be to decide upon how quickly we want our population to grow, or whether or not we need an upper and lower limit. In reviewing our historical experience, it would be reasonable to propose a relatively wide range, of say, 0.5 to 1 percent annually. For comparative purposes, the average population growth rate across the current 38 members of the OECD in 2023 was 0.5 percent, whereas across G7 nations (excluding Canada) the corresponding average was 0.3 percent. An upper limit of 1 percent might seem somewhat high to some, but such a target is not far from the rate at which our population has grown over the last half-century. Over the extended period 1971-2015, Canada’s population grew at an average rate of about 1 percent annually.

The basic idea here is that our society works with a predictable rate of population growth, from year to year, that avoids all of the disruptions that could be associated with very rapid growth or for that matter, stagnation or population decline. In doing so, our economy and social institutions would have an easier time accommodating our rate of population growth—avoiding the disastrous situation observed over the last couple of years.

Success in reducing the NPR population translates into higher immigration targets

In setting future targets on permanent immigration, our success in reducing the number of NPRs, put simply, should be considered key in setting future targets on permanent immigration. The basic idea here is that to the extent that we reduce the number of NPRs, we can correspondingly increase the number of landed immigrants without having an impact on population size. In promoting permanent immigration, we can restore best practices in terms of carefully selecting immigrants based on economic immigration, family reunification, and humanitarian considerations. This involves returning to the Canadian tradition whereby newcomers are given the promise in settling in this country that they could eventually obtain the rights of full citizenship.

The earlier projection showed future growth with little change in the number of NPRs, remaining indefinitely at 5 percent of the population total from 2027 onward. In the projection, landed immigrant targets were set to gradually climb from about 365,000 to a figure approaching 400,000 over the next decade or so. Yet if the target on NPRs were reduced further, down for example to about 3.5 percent, this could allow for hundreds of thousands of additional landed immigrants without having an impact on our rate of population growth. Of course, many of the NPRs currently living in Canada will not be leaving the country, but alternatively could be selected for landed immigrant status through our normal immigration streams.

On this front, in planning future immigration targets, it makes sense to further reduce the NPR share of Canada’s population well below the 2027 target of 5 percent. Considerable caution would be advised as to how to achieve this target, with the difficult balance here in meeting shorter-term labour force needs, promoting the best in our international student programs while continuing with our long history of meeting humanitarian commitments with asylum seekers.

Flexibility in our targeted growth

It is very difficult to come up with a simple formula for setting immigration targets—such that a well-informed population policy would continue to closely monitor the impact of population growth and the successful integration of newcomers. A targeted range of 0.5 to 1 percent annual population growth is meant to allow for some flexibility in responding to many of the pressing economic and social challenges that we currently face. In recently announcing its revised immigration plan, the federal government indicated that its new plan would allow for “[c]ontinued GDP growth, enable GDP per capita growth to accelerate throughout 2025 to 2027, as well as improve housing affordability and lower the unemployment rate.” As GDP per capita has been stagnant for several years now, this might be considered a tall order. On this front, there are obviously many factors beyond demography that will impact their relative success. Yet this announcement is consistent with the idea that if our unemployment rate rises or if Canada fails with its current housing plan, it is reasonable to reduce immigration targets accordingly.

In light of the many problems in Canada that were aggravated by the most recent surge in population (six years of growth in two), from housing affordability to access to health care, it would seem justifiable to set a population growth rate closer to the lower part of this range. And in light of the projections shared previously, this would imply lower immigration targets than in the current Liberal plan—unless the federal government has more success than expected in reducing the number of NPRs.

Time for a broader population policy

One of the most widely misunderstood impressions with regard to immigration is that it serves as a panacea to population aging. Yet one of the lessons that we can gain from this most recent surge in immigration is that Canada’s population will continue to age for some time regardless of immigration targets. In July of 2020, the median age in Canada was 40.8. By July of 2024, this median had fallen slightly to 40.3. This is after a population surge of over 3.3 million in merely four years. While international migrants are younger than the average Canadian, an unsustainable number would be required over the longer term to meaningfully slow and reverse this aging trend. Canada’s population will inevitably age over the next several decades, and a well-thought-out population policy should certainly prepare for this basic fact.

Although our population is younger today than it would be without international migration, the primary factor responsible for population aging has been the continued decline in our birth rate. Statistics Canada has in fact projected the impact of a continued decline, such that we could experience a negative natural increase within only a few years. With this in mind, the instinct to further reduce immigration over the longer term without a rebounding of our birth rate might be somewhat shortsighted. Canada seems set to become even more reliant on international migration in maintaining population and labour force levels, such that we will eventually need to raise immigration targets substantially even to meet a lower limit of 0.5 percent annual growth.

A broader population policy could shift our attention to our birth rate, rather than merely a reflex action to increase immigration. The basic fact that birth outcomes in Canada continue to be lower than birth intentions, is in itself worthy of policy intervention. Without a rebounding in our birth rate, population aging in Canada will accelerate. Canada will become even more reliant on immigration in maintaining population and labour force—unless, of course, Canadians decide that slow growth and/or population decline is preferable. Yet while rapid population growth has its challenges, so too does a shrinking population. One merely needs to turn to the Japanese example to fully appreciate this fact. A well-informed population policy could attempt to avoid both scenarios.