Adam: Racial minorities have more concerns than cash as PSAC strikes

2023/04/22 Leave a comment

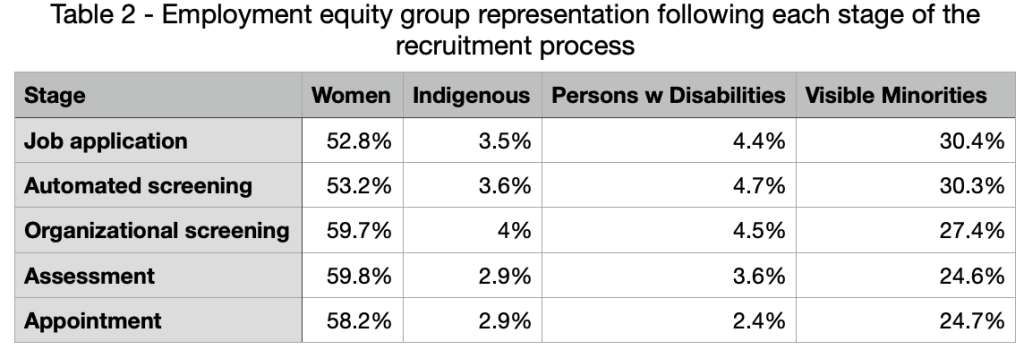

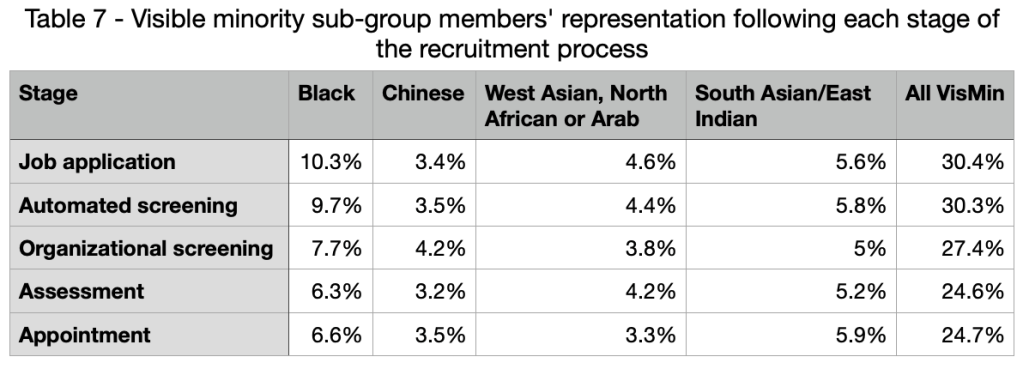

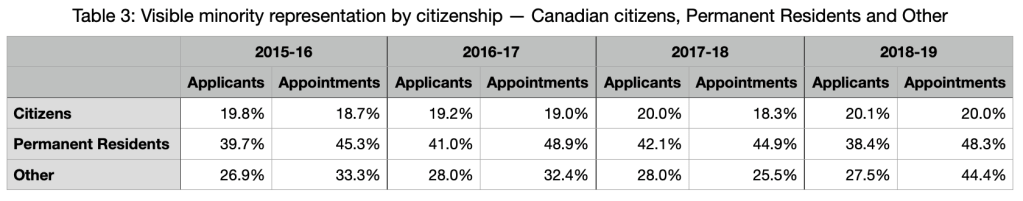

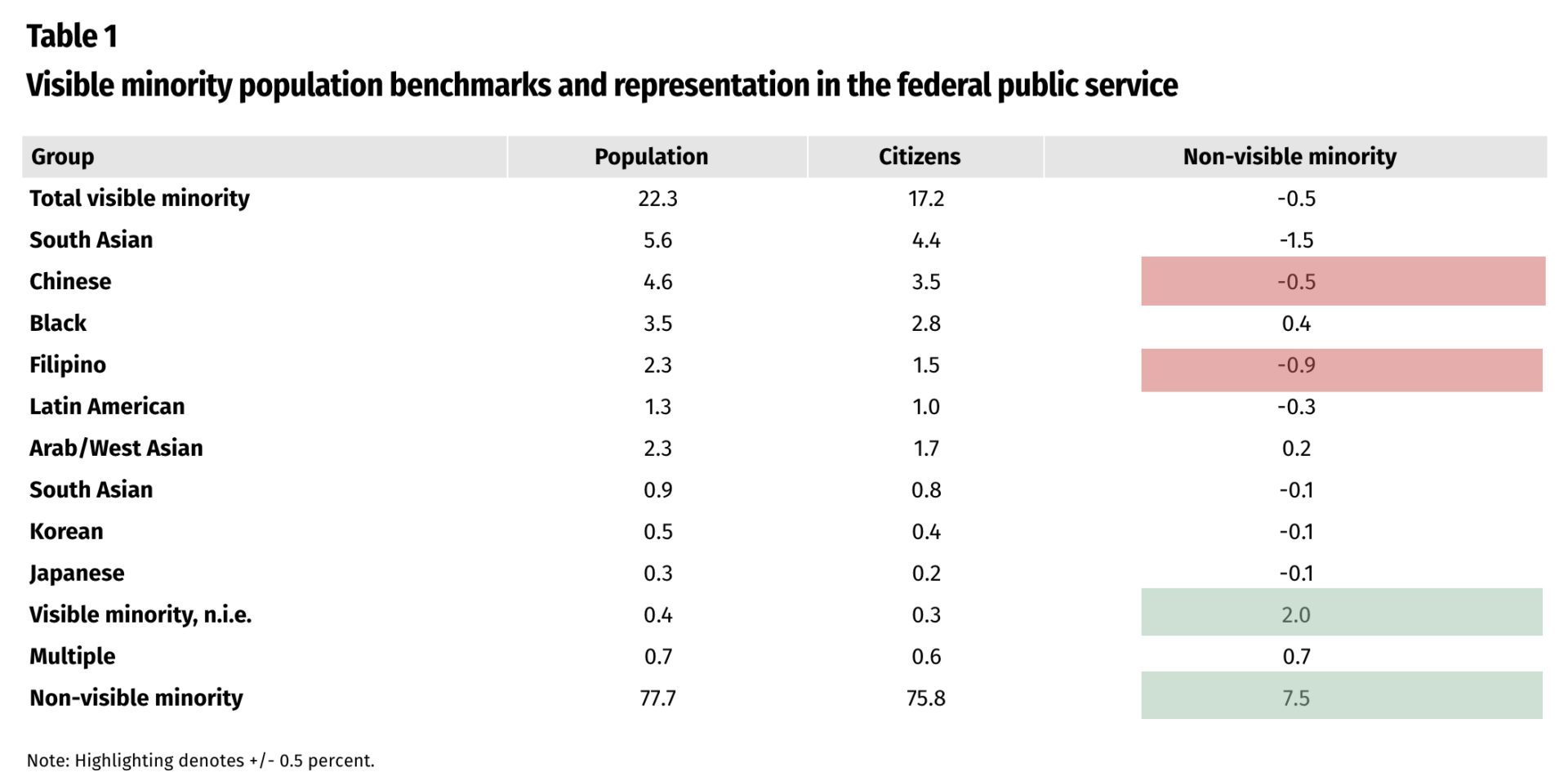

TBS desegregated visible minority and gender data for the last six years portrays increasing diversity, with net hirings (hirings less separations) and promotions significantly greater for visible minorities than not visible minorities. Highlights the danger of over-emphasizing personal stories rather than analyzing the data more closely:

Massive disruptions to government services were expected across the country as thousands of public servants went on strike this week in a dispute over wages and working conditions. The walkout affects 155,000 workers, but about 47,000, who are classified as essential workers, will remain on the job. That leaves some 100,000 for the picket lines.

The strike comes at a time when Canadians are struggling with the high cost of living, and many small businesses still have yet to fully recover from the effects of the pandemic. The public service union however, says its members have been affected by inflation, and is demanding a 4.5 per cent annual raise. At the time the strike was called, the federal government had offered three per cent, which the union rejected. The striking workers must walk a fine line to ensure public support because Canadians may be in no mood to tolerate a long walkout.

Significant as it is, the strike should not overshadow what, for many Black and other minority public servants, is an existential crisis: the lack of advancement that has confined them to low-paying entry-level jobs, and undermined their dignity and self-worth. Imagine working in the same job for 20 or 30 years and never getting a promotion. The shame of it is that this is what’s happening to Black and other minority employees of our federal government.

In the Citizen last week, Sandra Griffith-Bonaparte revealed how she never got a promotion in 22 years as a public servant at the Department of National Defence. It’s not because she lacks ambition. She worked hard to acquire two undergraduate degrees from Carleton University, as well as a master of arts and public ethics at St. Paul’s University and the University of Ottawa. She applied for numerous promotions but was rejected by her employer, watching as others climbed the job ladder and left her behind.

It was as if her employer was telling her she is not wanted; she doesn’t belong there. “Time and again, I’m either blocked, overlooked, ostracized, and this has me questioning: Why?” she said. “My story is not unique, this is happening all over in the Canadian government, in the public service in the city, in provincial workplaces.”

Indeed. Her case is a reflection of the discrimination many Black and minority people face in the public service: qualified people trapped in the same job for decades without any hope of progress or advancement, simply because of the colour of their skin.

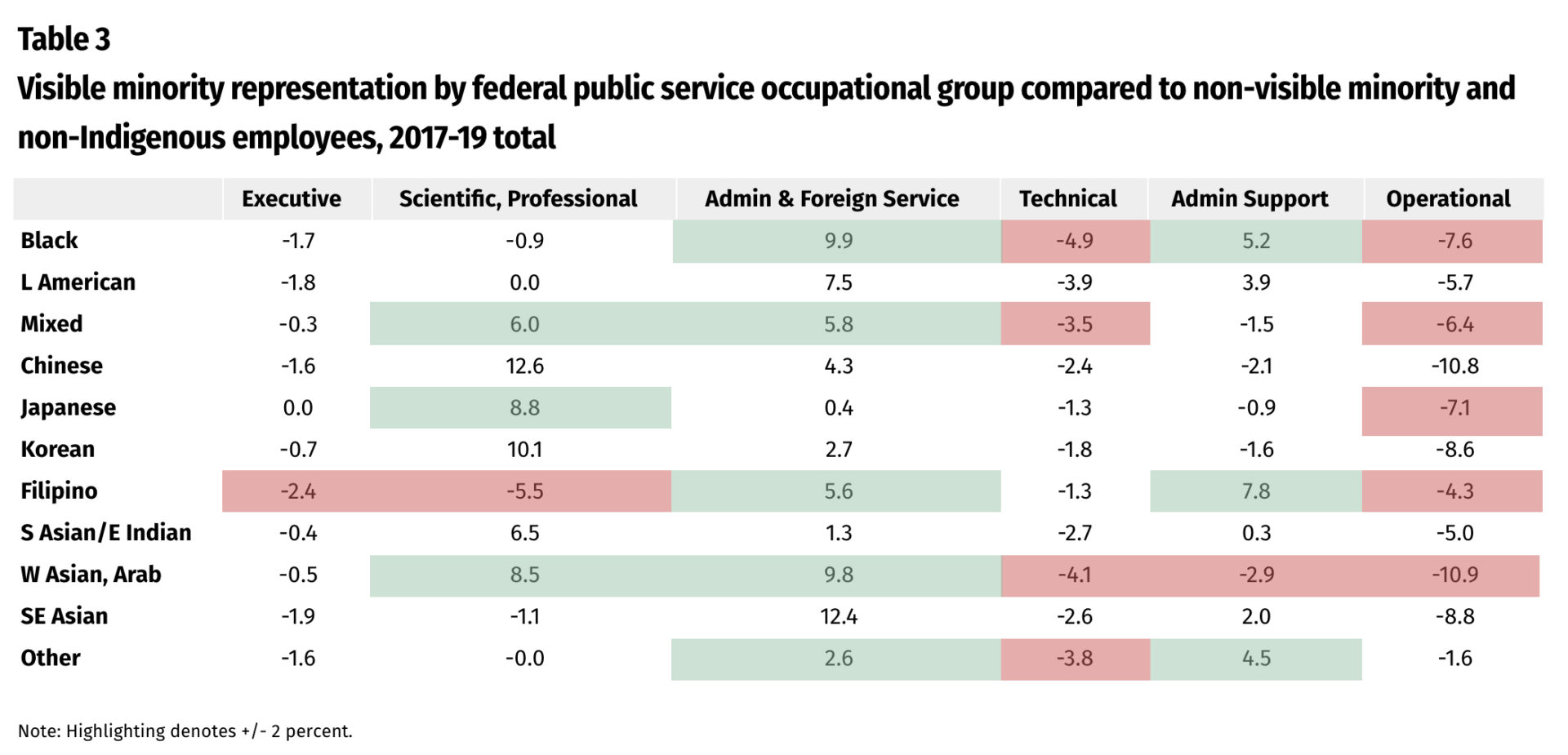

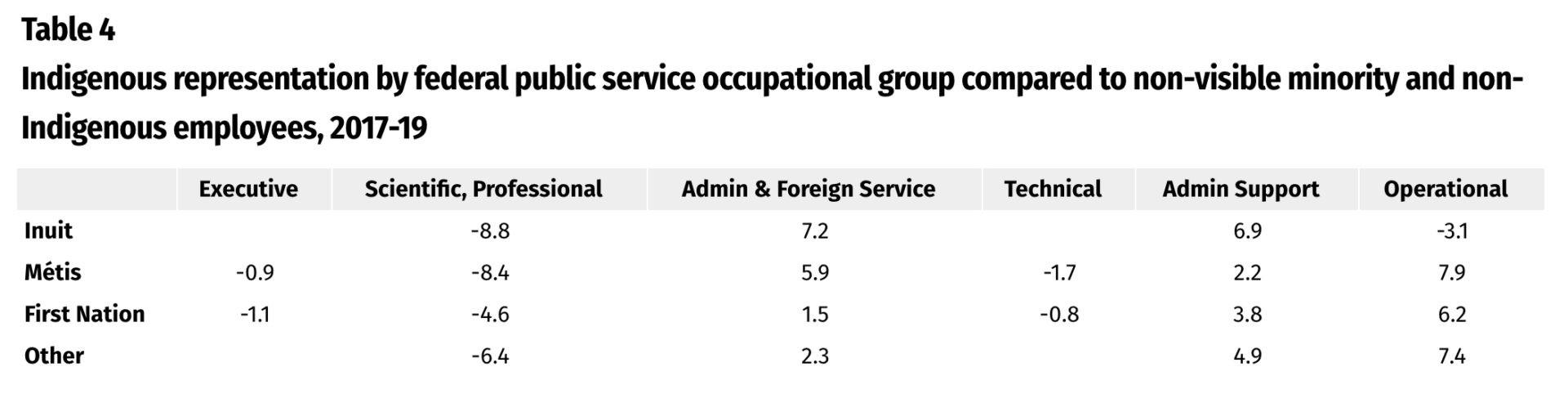

It shows in a 2021-22 Treasury Board employment equity report, which lays out how Indigenous people, Blacks and other members of so-called visible minorities continue to languish in the lowest salary ranks in the public service, while fewer and fewer of them are found in the higher levels.

It is this kind of discrimination that prompted a group of public servants to launch a lawsuit against the federal government seeking redress and compensation. The lawsuit highlights stories of others like Griffith-Bonaparte — people who have been toiling at the lower echelons of the public service for decades.

There is Carol Sip, a former Canada Border Services Agency employee whose supervisor constantly made derogatory remarks to her without management doing anything about it. She worked 26 years without promotion. Then there is Jennifer Phillips, who worked for the Canada Revenue Agency for 30 years and was promoted only once. Time and again, she watched as people she trained get promoted.

None of the claims in the class action lawsuit has been proven in court, but the sad thing is that these people were not looking to fill quotas or get preferential treatment. All they wanted was the same opportunity given to others to compete and advance on merit.

Responding to the equity report, Treasury Board president Mona Fortier promised the government would do better to build a more “inclusive and diverse” public service. When confronted with problems, politicians have a habit of offering comforting words without any real action. Federal workers are on strike for more money, but for racial minorities, there’s much more than cash at stake.

Mohammed Adam is an Ottawa journalist and commentator. Reach him at nylamiles48@gmail.com

Source: Adam: Racial minorities have more concerns than cash as PSAC strikes