When You Can’t Just ‘Trust the Douthat: Science’ The vaccine debate is the latest example of how our coronavirus choices are inescapably political.

2020/12/21 1 Comment

Overall, a good nuanced discussion of where the science largely ends and values and ethnics inform (or not) political choices. The one major weakness in his arguments is that while a focus on seniors primarily means a focus on whites, personal care and healthcare workers tend to be significantly non-white, and so there is less of a contradiction than he assumes:

One of many regrettable features of the Trump era is the way that the president’s lies and conspiracy theories have seemed to vindicate some of his opponents’ most fatuous slogans. I have in mind, in particular, the claim that has echoed through the liberal side of coronavirus-era debates — that the key to sound leadership in a pandemic is just to follow the science, to trust science and scientists, to do what experts suggest instead of letting mere grubby politics determine your response.

Trump made this slogan powerful by conspicuously disdaining expertise and indulging marginal experts who told him what he desired to hear — that the virus isn’t so bad, that life should just go back to normal, usually with dubious statistical analysis to back up that conclusion. And to the extent that trust the science just means that Dr. Anthony Fauci is a better guide to epidemiological trends than someone the president liked on cable news, then it’s a sound and unobjectionable idea.

But for many crucial decisions of the last year, that unobjectionable version of trust the science didn’t get you very far. And when it had more sweeping implications, what the slogan implied was often much more dubious: a deference to the science bureaucracy during a crisis when bureaucratic norms needed to give way; an attempt by para-scientific enterprises to trade on (or trade away) science’s credibility for the sake of political agendas; and an abdication by elected officials of responsibility for decisions that are fundamentally political in nature.

The progress of coronavirus vaccines offers good examples of all these issues. That the vaccines exist at all is an example of science at its purest — a challenge posed, a problem solved, with all the accumulated knowledge of the modern era harnessed to figure out how to defeat a novel pathogen.

But the further you get from the laboratory work, the more complicated and less clearly scientific the key issues become. The timeline on which vaccines have become available, for instance, reflects an attempt to balance the rules of bureaucratic science, their priority on safety and certainty of knowledge, with the urgency of trying something to halt a disease that’s killing thousands of Americans every day. Many scientific factors weigh in that balance, but so do all kinds of extra-scientific variables: moral assumptions about what kinds of vaccine testing we should pursue (one reason we didn’t get the “challenge trials” that might have delivered a vaccine much earlier); legal assumptions about who should be allowed to experiment with unproven treatments; political assumptions about how much bureaucratic hoop-jumping it takes to persuade Americans that a vaccine is safe.

And the closer you get to the finish line, the more notable the bureaucratic and political element becomes. The United States approved its first vaccine after Britain but before the European Union, not because Science says something different in D.C. versus London or Berlin but because the timing was fundamentally political — reflecting different choices by different governing entities on how much to disturb their normal processes, a different calculus about lives lost to delay versus credibility lost if anything goes wrong.

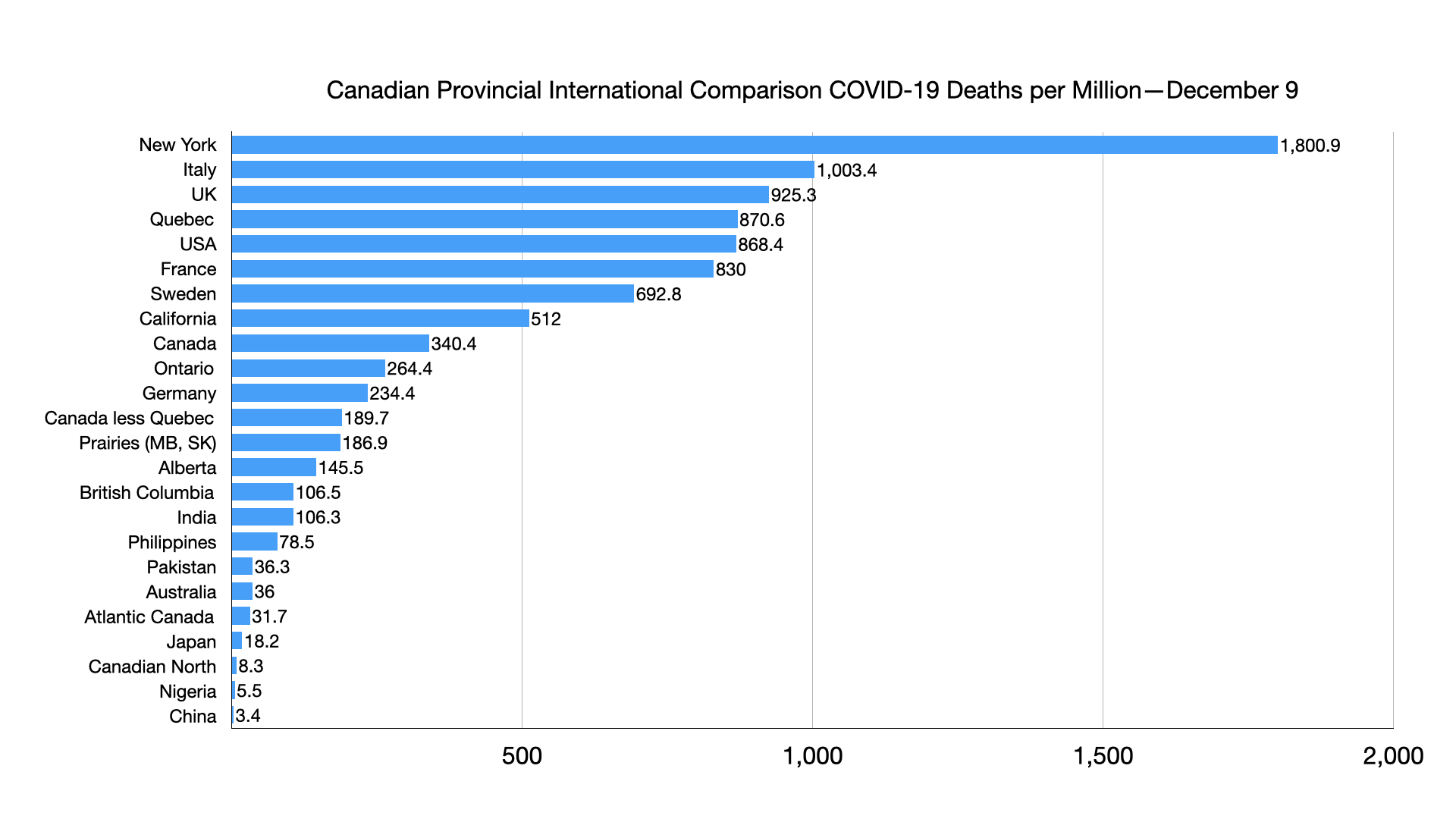

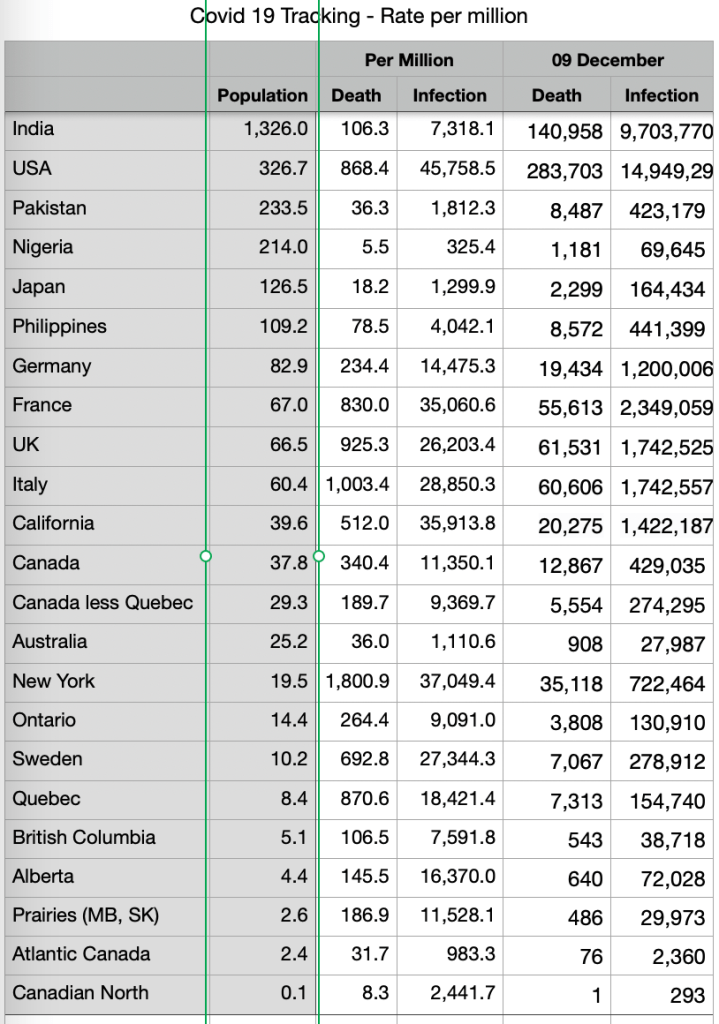

Then there’s the now-pressing question of who actually gets the vaccine first, which has been taken up at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in a way that throws the limits of science-trusting into even sharper relief. Last month their Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices produced a working document that’s a masterpiece of para-scientific effort, in which questions that are legitimately medical and scientific (who will the vaccine help the most), questions that are more logistical and sociological (which pattern of distribution will be easier to put in place) and moral questions about who deserves a vaccine are all jumbled up, assessed with a form of pseudo-rigor that resembles someone bluffing the way through a McKinsey job interview and then used to justify the conclusion that we should vaccinate essential workers before seniors … because seniors are more likely to be privileged and white.

As Matthew Yglesias noted, this (provisional, it should be stressed) recommendation is a remarkable example of how a certain kind of progressive moral thinking ignores the actual needs of racial minorities. Because if you vaccinate working-age people before you vaccinate older people, you will actually end up not vaccinating the most vulnerable minority population, African-American seniors — so more minorities might die for the sake of a racial balance in overall vaccination rates.

But even if the recommendation didn’t have that kind of perverse implication, even if all things being equal you were just choosing between more minority deaths and more white deaths in two different vaccination plans, it’s still not the kind of question that the C.D.C.’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices has any particular competency to address. If policy X leads to racially disparate death rates but policy Y requires overt racial discrimination, then the choice between the two is moral and political, not medical or scientific — as are other important questions like, “Who is actually an essential worker?” or “Should we focus more on slowing the spread or reducing the death rate?” (Or even, “Should we vaccinate men before women given that men are more likely to die of the disease?”)

These are the kind of questions, in other words, that our elected leaders should be willing to answer without recourse to a self-protective “just following the science” default. But that default is deeply inscribed into our political culture, and especially the culture of liberalism, where even something as obviously moral-political as the decision to let Black Lives Matter protests go forward amid a pandemic was justified by redescribing their motor, antiracism, as a push for better public health.

When we look back over the pandemic era, one of the signal failures will be the inability to acknowledge that many key decisions — from our vaccine policy to our lockdown strategy to our approach to businesses and schools — are fundamentally questions of statesmanship, involving not just the right principles or the right technical understanding of the problem but the prudential balancing of many competing goods.

On the libertarian and populist right, that failure usually involved a recourse to “freedom” as a conversation-stopper, a way to deny that even a deadly disease required any compromises with normal life at all.

But for liberals, especially blue-state politicians and officials, the failure has more often involved invoking capital-S Science to evade their own responsibilities: pretending that a certain kind of scientific knowledge, ideally backed by impeccable credentials, can substitute for prudential and moral judgments that we are all qualified to argue over, and that our elected leaders, not our scientists, have the final responsibility to make.

Source: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/19/opinion/sunday/coronavirus-science.html