There are plenty of tough jobs in Ontario right now: From those moving parcels at Amazon warehouses to those guiding i-beams at a condo construction site, workers are facing the grim of reality of the pandemic.

Workers are going to the job site everyday without the guarantee of sick pay if they fall ill, need to get tested or snag a much-coveted vaccination spot.

There is one particular job that might not carry the same risks, but which still isn’t inspiring much envy these days: Being a member of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Table.

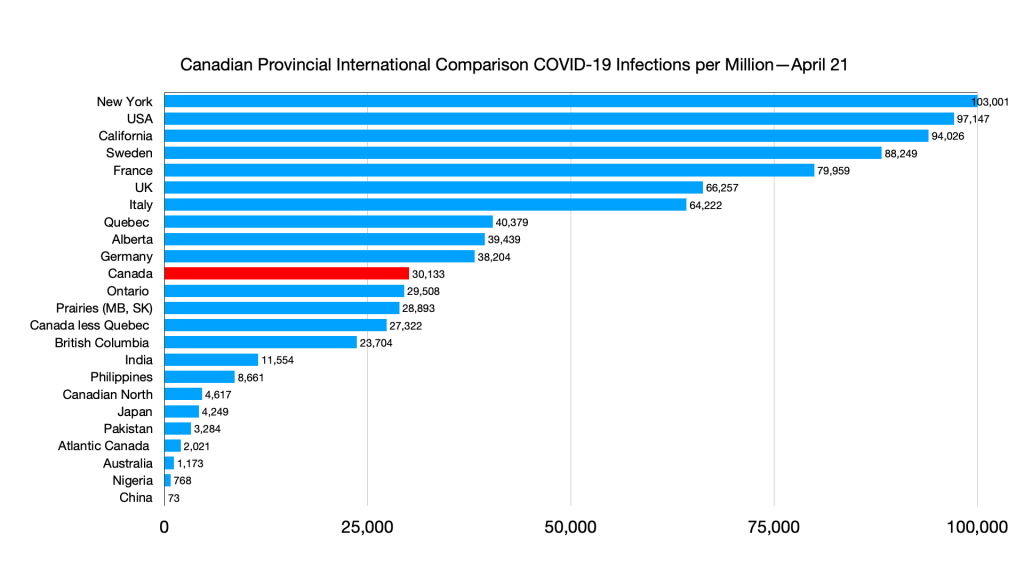

The Table, composed of some 100 doctors, researchers and specialists, is the independent body that furnishes advice to Premier Doug Ford and his cabinet on how best to beat back the deadly pandemic. It is their modelling that shows Ontario careening towards 30,000 news cases per day.

But it was their advice—to shut truly non-essential workplaces, pause construction where possible, and prioritize more vaccines for front-line workers—that was summarily ignored.

Instead, they dispatched officers to police a pandemic: As a pre-teen in Gravenhurst recently found out. They promised more inspectors, but that means very little if the provincial regulations allow employees to remove their masks on the job—a recent outbreak at a provincial testing laboratory shows that nowhere is truly safe from the virus.

The whole Table is in an impossibly awkward spot. Ford continues to tout their work, insisting it has informed his own approach to the pandemic. But, in practise, his actions have consistently been directly at odds with the advice from the Table.

Last week, as the divergence between advice and action grew wider, talk around the Table turned to mass resignation. A protest, in essence, of being used by a government that appears to have little interest in a science-based approach to fighting the pandemic.

But the majority of the Table opted, instead, for a softer approach: One that retains cautious optimism that the Ford government may yet see the light, and pursue measures that may actually avert a worst-case scenario in the province.

To underscore their position, the Science Table drafted a letter to the government with pointed advice on what to do next. It’s a letter that lays out the choice the Ford government faces. Whether or not he will make the right decision is, ultimately, up to him.

***

On Friday afternoon Dr. Adalsteinn Brown, the co-chair of the Science Table, appeared alongside Dr. David Williams, the province’s Chief Medical Officer of Health to present new modelling on the risks facing the province.

“Without stronger system-level measures and immediate support for essential workers and high-risk communities, high case rates will persist through the summer,” the presentation warned.

Brown said financial support for workers and strict measures for workplaces were desperately needed: “We need to stop infection coming into our central workplaces,” he said.

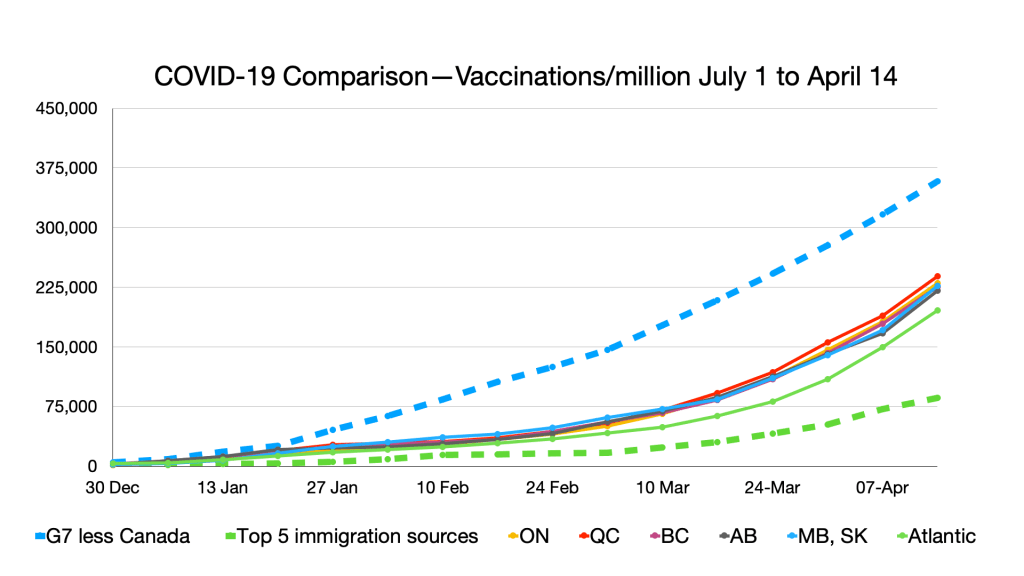

Vaccines, he added, were a central part of the strategy but wouldn’t solve this problem on their own.

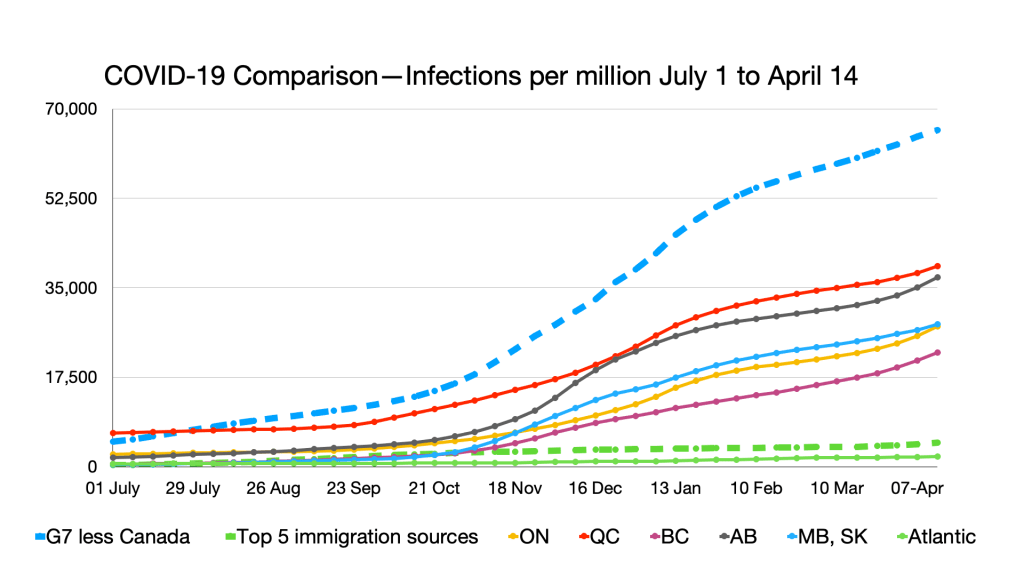

The lines on the graph were three colours: Green, which rose slightly, then bent towards the X-axis. Yellow, which wobbled upwards so slightly—hovering right above 10,000 cases per day. And, finally, the red line: A line that sloped menacingly upwards, past the 30,000 marker.

Ontario is currently trending along the yellow line.

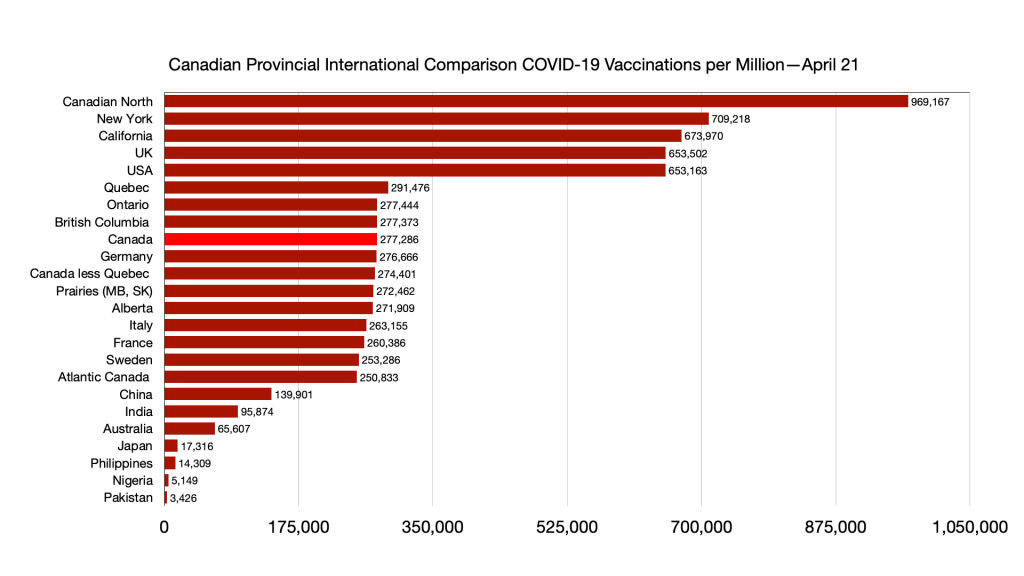

Red, yellow, and green dotted lines shadowed each of the solid lines: They represented what case counts would look like if Ontario managed to ramp up from the status quo, 100,000 vaccines administered per day, to an arbitrary number of 300,000 shots per day.

“Under every scenario, more vaccines mean a faster resolution in the long-run,” the presentation explained.

The Table communicated the crisis looming, and provided clear advice on how to avert disaster—both publicly and privately.

Hours later, after prolonged cabinet discussions, Ford appeared in front of television cameras to announce his decision: Playgrounds and outdoor sports would be banned. Outdoor gatherings forbidden, for members outside our household. Police would be dispatched to enforce the orders, with nearly-limitless authority to stop and question anyone in public. More inspectors would be dispatched to workplaces, but there would be no meaningful change to what constituted an ‘essential’ workplace. The number of vaccines reserved for frontline workers in hotspot zones would be set at 25 per cent.

The premier waved a sheet from Brown’s presentation: The chart showing the case projections. He seized on the idea that 300,000 vaccines could blunt this punishing third wave. “Would we be in this position if we were getting 300,000 doses a day back in February? Like the rest of the world? The answer is absolutely not,” Ford said.

The province looked on in alarm. The premier was, effectively, announcing a police state. Meanwhile, he was ranting at the federal government for not sending enough vaccines. When asked directly why he couldn’t shut more businesses, Ford explained how “deep” the supply chains were—light switches wouldn’t be made, he explained.

Reaction from the public was swift, and horrified. But the members of the Science Table, in particular, were beside themselves. Brown and fellow co-chair Brian Schwartz sent an email to dozens of his colleagues on the Science Table.

“We know that many of you are frustrated and angry after today’s announcements,” Brown and Schwartz wrote.

“We did the right thing,” they wrote of their early afternoon briefing, which set the stakes for Ford’s 4 pm announcement. The research and data, furnished by members of the table, they wrote: “Made it possible for us to be firm in saying what we know should be done to fight the pandemic.”

Several members of the Table took to Twitter to blast the decision. One member, Dr. Andrew Morris—who is a University of Toronto professor of medicine, a medical director in the Sinai Health System, and who co-chairs the Table’s working group on drugs and biologics—called the decision “criminal.”

Many of their blistering repudiations of the government’s decision were splashed on the frontpage of the Toronto Star on Saturday morning.

Brown and Schwartz didn’t discourage the comments. “The only thing we would ask is that you speak truth to power in the same way you would conduct any other discussion,” they wrote.

They summed up, in bullet points, the recommendations and analysis they had been providing for weeks: More vaccines for high-risk communities, close businesses that are not absolutely necessary, do more to protect workplaces that must remain open, create dedicated sick leave benefits, reduce mobility within the province, and encourage people to meet outside safely.

“Unfortunately, our advice does not align with what the cabinet announced this afternoon,” they wrote. “That requires serious discussion.”

Brown and Schwartz signed off the email, recognizing that many of the members were actually on the front-lines of this deadly fight. For those still on clinical duty, they wrote, “we wish you and your patients the very best through this exceptionally challenging weekend, and that you get a few moments of rest too.”

They arranged a 10 am Sunday morning meeting to discuss next steps.

In the outside world, pressure was mounting. Registered Nurses Association of Ontario CEO Doris Grinspun called for the Science Table to “resign en-masse.”

***

On Saturday afternoon, the Ford government appeared to walk back its enforcement measures, which would have given police nearly unfettered power to stop and interrogate people out for a walk, or driving, and ask their home address and purpose for being out in public.

The retreat came after nearly every police force in the province said they would refuse to conduct the arbitrary stops—journalist Andrew Lawton found that only the Ontario Provincial Police said they would enforce the measures.

Yet the supposedly walked-back regulations still allow police to stop anyone on the suspicion that “an individual may be participating in a gathering that is prohibited.” Of course, provincial regulations now ban any outdoor gathering, except for those in the same household. The new regulations allow police to demand the individual provide “information for the purpose of determining whether they are in compliance with that clause.”

Lawyers pointed out that the new, supposedly “refocused,” measures actually gave police more power to interrogate Ontarians on flimsy grounds. A group of young skateboarders in Gravenhurst would learn that reality pretty quickly on Sunday morning. Leanne Bonnekamp’s 12 year old son was out skateboarding with friends—in a park near the YMCA, as the skate parks were closed by provincial order. That’s when a cop approached.

“Two officers showed up, yelled at these kids—that they weren’t wearing masks, and weren’t socially distanced,” the boy’s mother, Bonnekamp, told me. One of the Ontario Provincial Police officers demanded the kids’ ID, and was running it in his cruiser as his partner stayed with the other youth.

Bonnekamp’s son was giving the officers attitude for the arbitrary stop—though no profanity, she says—as the cop gripped his scooter. In the video, the officer can be seen reaching over the scooter and shoving the pre-teen, who falls on the ground. When another youth asks just what in the hell the officers are doing, the cop yells “he’s failing to identify.”

The OPP says they are investigating the officer’s actions.

The same weekend, an outbreak in Toronto put into sharp focus the inadequacy of the government’s workplace measures. An outbreak of cases in a Toronto lab, run by Public Health Ontario to analyze COVID-19 tests, infected 16 employees.

The agency’s president Colleen Geiger sent an email to staff, which was forwarded to Maclean’s, indicating an investigation into the outbreak was ongoing and that they would identify “areas that require improvement.” Close contacts of those who tested positive, Geiger wrote, were already isolating. Other staff would be tested onsite.

One employee, who contacted Maclean’s with details of the outbreak but asked to remain anonymous because they were not authorized to speak to media, said the outbreak was just waiting to happen. Social distancing in the lab is nearly impossible and good public health measures aren’t being enforced, they wrote. Masks are often worn improperly and limits posted by the lunch tables and elevators aren’t respected.

This outbreak isn’t even the first. Previous instances where employees of the lab caught COVID-19 are “posted on bulletin boards that are tucked away in corners of hallways.”

The employee, quite correctly, argued that “Public Health of Ontario should hold a higher standard than the rest of Ontario residents and I find it shameful that this outbreak could have been avoided.”

Public Health Ontario confirmed to Maclean’s that 16 staff fell ill. “Diagnostic testing for COVID-19 as well as other infectious diseases are continuing as normal and there is no impact on laboratory services at this time,” they wrote.

If the provincial lab responsible for processing COVID-19 tests can’t even keep safe, how much trust can we put in other workplaces?

***

Sunday morning, Dr. David Fisman—professor of epidemiology at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto, and a member of the Science Table—wrote to the other members: “My concern is that the science and modeling tables are being used as cover.”

“What we saw on Friday was exactly the sort of thing I’ve been concerned about: Meaningful guidance from this group was disregarded,” he continued. “But the premier took the time to hold up a graph in which a hypothetical 300,000 vaccines per day scenario was plotted, and indicated that this would be the way forward.”

“As I have said at our meetings, at some point this starts to feel like aiding and abetting a government that has prosecuted a pandemic response that frankly feels negligent, or even criminal,” Fisman wrote.

“I don’t think I am on the same team as this government.”

That intense frustration was shared by many of his colleagues.

In an interview with Maclean’s, Morris said he was “dumbfounded” by the Friday announcement. At the same time, he called it an “apex” of a trend that has been growing over the course of the pandemic.

“When we get to Friday, they come out with these measures that are absolutely antithetical to the beliefs and advice of the Science Table — en masse, and individual members,” Morris says. “I don’t think there’s a single member who would have recommended those things.”

He phrases it as a consistent and repeated “gaslighting” by the government.

“Friday, for me, was probably my darkest day in my professional career,” says Dr. Peter Jüni, the scientific director for the Science Table—who is also a world-renowned researcher and a professor at the University of Toronto.

Jüni told me he found himself asking: “Were we not clear enough?”

“It’s pretty clear that there is a gulf between what the Science Table has recommended and what the policy announced in the province was. That’s clear,” says Dr. Isaac Bogoch who sits on the Table’s modelling working group, teaches at the University of Toronto, and who consults on infectious disease outbreaks at the Toronto General Hospital.

When the entire Table joined a Zoom call on Sunday morning, there were divergent views on what to do. Some wanted them all to resign, as a show of force that the government couldn’t use their modelling but ignore their advice.

But, as Bogoch notes, the public outcry about the measures actually prompted a retreat. The Ford government, perhaps more than the average government, is intensely sensitive to criticism. The Table’s advice—enabled by their independence, both from government and from any kind of particular hierarchy—no doubt enabled that public backlash.

There was also some pessimism about whether resigning would have much impact.

“I’m not sure, personally, what resignation would do,” Morris confesses. Bogoch agrees: They still have a job to do, he says. Being ignored “doesn’t mean you fold up your tent.”

Jüni, who publicly mused about resigning, came to a similar conclusion. “I could make a point, not a difference,” he says.

One feeling is particularly stark: The Science Table fears what, if anything, will replace their advice and modelling if they leave.

“There’s no question there are times, it has felt to many people, like we’ve been played,” Morris says. With resignation off the table, his mind turned to: “How can we avoid being played like that?”

***

What, exactly, the Ford government is going to do next is an open question. On Monday, after a brutal weekend for the Ford government, I got on the phone with someone in the Premier’s office. We agreed on anonymity so they could speak freely.

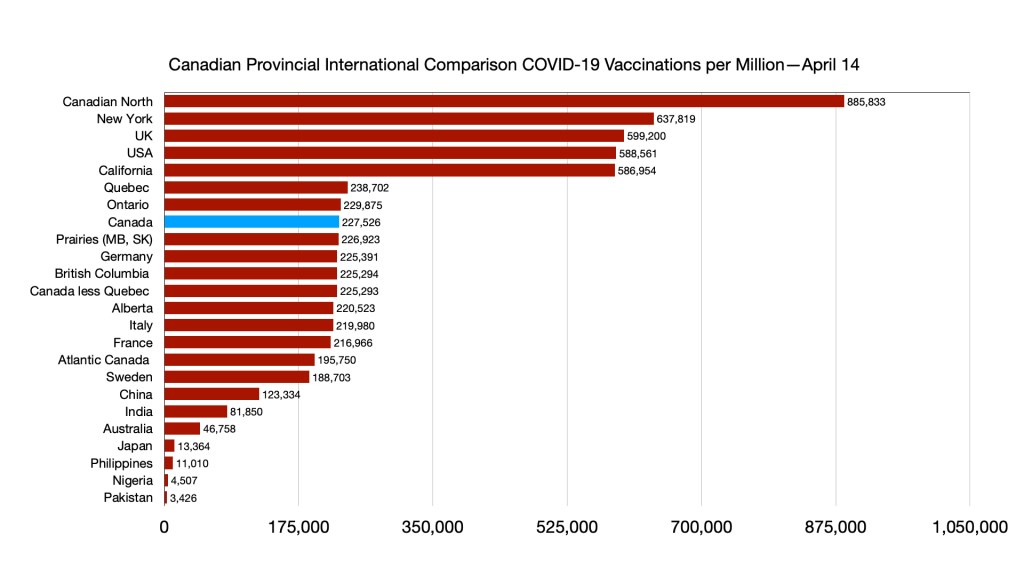

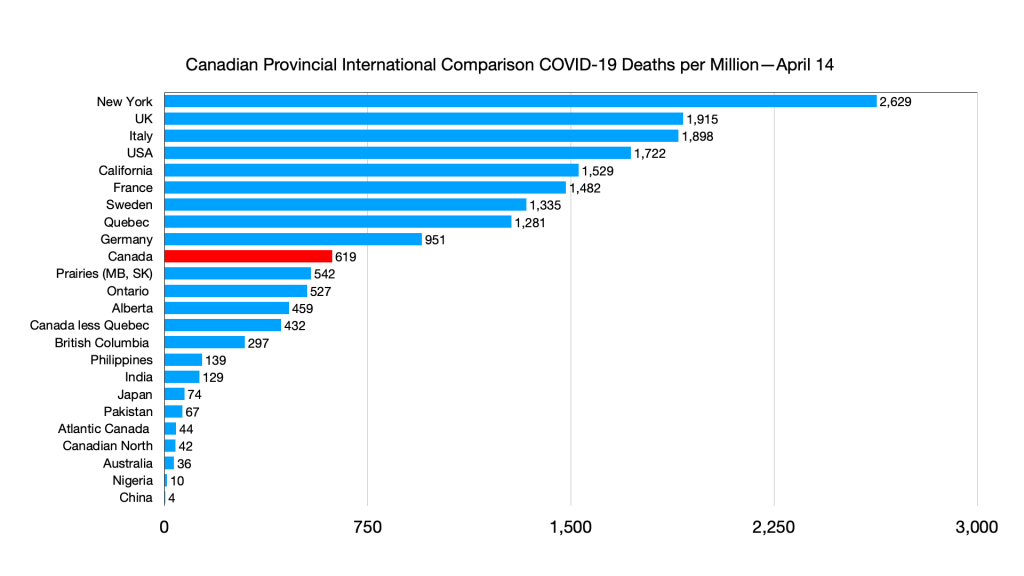

They certainly acknowledged the blowback that came from Friday’s announcement, and recognized more action would be necessary to stem the transmission of the virus. And they were quick to highlight the areas where they did, general speaking, follow the Science Table’s advice. Chiefly, Ford announced his government would dedicate 25 per cent of the vaccine supply for frontline workers in hotspot neighbourhoods.

The Science Table, I pointed out, recommended allocating 50 per cent of the vaccine supply. The government source said: Well, if we had done 50 per cent, they would have called for 75 per cent.

At another point, I noted that the Science Table was apoplectic about how virtually nothing was being done to shut truly not crucial construction projects. Yes, the source said, but the construction industry was furious.

(Indeed, the Ontario Construction Consortium attacked the government’s order barring non-essential construction, bizarrely insisting that “a recent snapshot of 10,000 Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) claims related to COVID-19 since the pandemic began showed that fewer than 200 of those cases originated in the construction industry.” Provincial data shows that, since the start of the pandemic, some 10,000 cases were a direct result of outbreaks at offices, warehouses, and construction sites.)

But the balancing act this government is striving for is exactly the problem: Splitting the difference, or trying to strike a balance between rigorous scientific advice and the construction lobby is not a wise or successful move.

“How does a cabinet—that has even a rudimentary understanding of what’s going on—how do they deliberate over numerous hours over two days and come up with this?” Morris asked me.

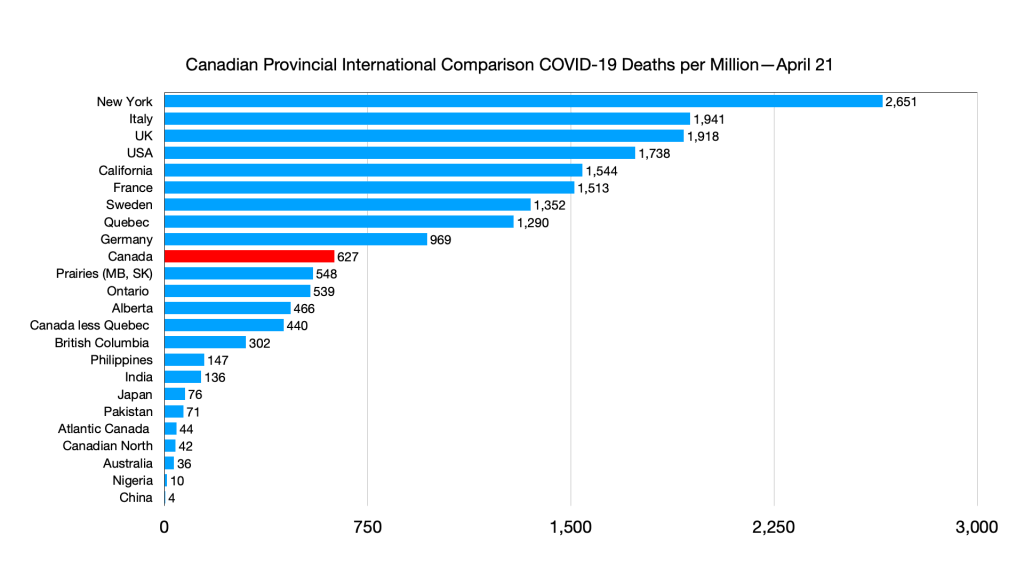

“If you do half measures, you hurt everybody,” Jüni says. “Including the economy.”

The province has dedicated more inspectors for these workplaces, but its own advice is faulty: The Government of Ontario’s official policy on masks in the workplace holds that “you do not need to wear a face covering when you are working in an area that allows you to maintain a distance of at least 2 metres from anyone else while you are indoors.” (The provincial regulations state that workers may be maskless if they can maintain social distancing and are in an area inaccessible to the public—a construction site, for example.)

That is a fundamentally backwards policy that ignores the strong likelihood of airborne transmission. If workplace inspectors are continuing to enforce that standard, the inspections are going to be largely ineffective.

Things that the science table believes are going to be helpful is more support for workers, essential workers, to access support—primarily financial support so that they can get vaccinated, tested or stay away from work if they’re unwell.

When asked directly whether the government would finally retreat, and ensure sick leave for workers in the province, the government source said they were waiting to see whether Monday’s federal budget would do the job for them. Even though labour law, including sick leave, is explicitly provincial domain, they said, they wanted Ottawa to act.

The federal budget did, in fact, expand the Employment Insurance sickness benefit—but that support is claims-based, meaning it isn’t automatic nor does it mean much for an employee who suddenly falls ill. Those employees, clearly, need sick leave: Something many employers still refuse to provide, but which the provincial government can mandate.

The government source said, despite the Ford government’s dogmatic opposition to date, the government would give “serious consideration” to sick leave. But it would be unlikely any decision would be made anytime in the near future.

Part of the Ford government’s commitment to the status quo seems to stem from their belief that things are heading in the right direction. The government source said that, while things may change fast—and new ICU admissions could force their hand—they do not anticipate announcing new measures this week.

Asked where this optimism was coming from, the source pointed to the mobility data found in the Science Table’s modelling showing that, in recent weeks, fewer people have been travelling outside their home. If mobility trends downward, they think, case counts will flatten.

But that, too, runs contrary to the advice from the Science Table. “Mobility is a surrogate for contact,” Jüni says. “It’s a marker. It isn’t causal.”

As Jüni points out, declining mobility could be a sign that, through general anxiety or enforcement measures, people are staying indoors—a good sign, if social gatherings are driving transmission.

Provincial data shows that a significant number, likely the majority, of COVID-19 cases in the province are coming from workplaces and schools. I asked for data to prove that private gatherings were driving significant caseloads, but have yet to receive it.

On the flipside, however, mobility trends might not mean much if Ontarians are leaving home to engage in low-risk activity, like meeting friends in a park, or going for a walk.

The more I cited the Science Table’s work, the more the government source suggested the advice was at odds with itself. Or unclear. Or, for example, that the Table couldn’t agree on advice about the safety of gathering outdoors.

The Table doesn’t see it that way. Jüni himself presented before cabinet. “Outdoors is safe,” he told them. It can be made more safe, he added, but he says he was abundantly clear. “I do not know what more I could do,” he says.

Morris echoes the sentiment: He says it is “essential” that the province provide clear advice, encouraging outdoor activity.

***

On Tuesday afternoon, the Science Table issued a letter to the Ford government, entitled: The Way Forward.

“Ontario is now facing the most challenging health crisis of our time,” the Table wrote. “Our case counts are at an all-time high. Our hospitals are buckling. Younger people are getting sicker. The disease is ripping through whole families. The Variants of Concern that now dominate COVID in Ontario are, in many ways, a new pandemic. And Ontario needs stronger measures to control the pandemic.”

The letter put to paper, publicly, what the Table has been telling the Ford government emphatically since the third wave began swelling.

It proposed clear strategies—things the Ford government is pointedly not doing:

- Reducing the list of essential workplaces allowed to remain open to be “as short as possible,” and ensuring that those workers wear masks on the job.

- “Paying essential workers to stay home when they are sick.” And not, they note, the federal Employment Insurance benefit, which is “cumbersome” and inadequate.

- Allocating as many vaccine doses as possible to hotspot communities and essential workers—and ensuring “on-the-ground community outreach” to connect doses to those workers.

- Providing “public health guidance that works.” That means communicating a simple message: Indoor gatherings should be strictly forbidden, while underlining that “Ontarians can spend time with each other outdoors” while social distancing. That means allowing small gatherings of people from different households, while also encouraging masks and two metres distance.

The letter warns that “inconsistent policies, with no clear link to scientific evidence, are ineffective in fighting COVID.” That includes, they wrote, policies that “discourage safe outdoor activity.”

The premier isn’t mentioned by name in the letter, but the closing lines offer a stark warning for the government:

“There is no trade-off between economic, social and health priorities in the midst of a pandemic that is out of control.”