Human rights commission acknowledges it has been dismissing racism complaints at a higher rate

2023/03/25 Leave a comment

More on the CHRC with a note of caution to those advocating for direct access to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, rather than going through the Commission from Cindy Blackstock, the main advocate for the First Nation children harmed by Canada’s discriminatory child welfare system:

The Canadian Human Rights Commission’s recent numbers show it has been dismissing racism-based claims at a higher rate than other human rights complaints — but the commission insists it’s working to change that.

Numbers the commission provided to CBC News show that in most of the past five years, it reported a higher rejection rate for claims based on racism than for other complaints.

The statistics released by the commission show that during the first three years of the 2018-2022 period, the commission dismissed a higher percentage of race-based claims than it did others.

The year 2020 saw the largest disparity. The percentage of racism-based complaints the commission rejected — 13 per cent — was almost double the percentage of other types of claims it rejected (7 per cent).

The commission accepted more racism-based claims in subsequent years, referring them either to mediation or to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal. Last year, for example, the commission dismissed only nine per cent of racism-based claims, compared with a 14 per cent rejection rate for other types of claims

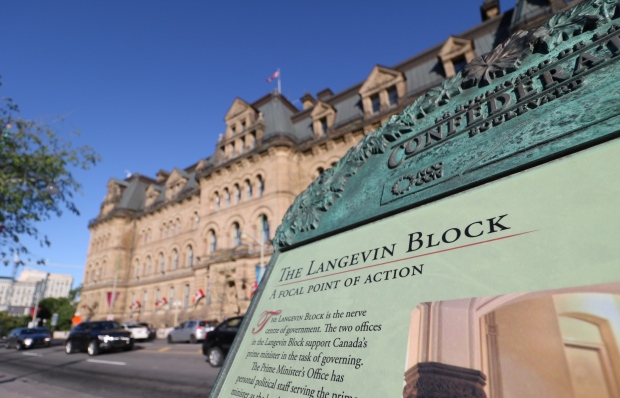

The commission describes itself as Canada’s human rights watchdog. It receives and investigates complaints from federal departments and agencies, Crown corporations and many private sector organizations such as banks, airlines and telecommunication companies. It decides which cases proceed to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal.

The commission released the data after the federal government concluded recently that the commission had discriminated against its Black and racialized employees.

The Canadian government’s human resources arm, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBCS), came to that conclusion after nine employees filed a policy grievance through their unions in October 2020. Their grievance alleged that “Black and racialized employees at the CHRC (Canadian Human Rights Commission) face systemic anti-Black racism, sexism and systemic discrimination.”

“I declare that the CHRC has breached the ‘No Discrimination’ clause of the law practitioners collective agreement,” said Carole Bidal, an associate assistant deputy minister at TBCS, in her official ruling on the grievance.

A group of current and former commission employees who spoke to CBC News said they’ve noticed all-white investigative teams dismissing complaints from Black and other racialized Canadians a higher rate.

CBC has requested interviews with the CHRC’s executive director Ian Fine and interim chief commissioner Charlotte-Anne Malischewski. The commission has declined those requests because it says the matter is in mediation.

In a media statement, the commission has said it accepts the TBCS’s ruling and is working to implement an anti-racism action plan.

Véronique Robitaille, the commission’s acting communications director, said the commission has been compiling data in the course of that work. The latest figures, she said, show the commission is taking action to address the concerns.

“The following data … shows the results of our ongoing actions to address concerns related to the handling of complaints filed on the grounds of race, colour, and/or national or ethnic origin,” Robitaille said in a media statement to CBC News.

Robitaille said the percentage of race-based complaints referred to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal has doubled between 2017 (9 per cent) and 2021 (18 per cent). In 2021, the commission said it implemented a modernized complaint process that modified how it screens complaints based on race, colour and/or national or ethnic origin.

‘Racism runs amuck’

The people behind the cases the commission dismissed in recent years say they’re still waiting for justice.

Rubin Coward is one of them. The former member of the Royal Canadian Air Force told CBC News that he filed a complaint with the commission in 1993 alleging he experienced racism and was repeatedly called the N-word while stationed at CFB Greenwood in Nova Scotia. His claim was rejected.

Now a Nova Scotia community-based advocate for military, RCMP members and seniors, he regularly helps people file human rights complaints. He said he’s noticed that the ones that have nothing to do with race tend to be more successful.

“I was severely disappointed but I wasn’t surprised,” said Coward, reacting to the news that the CHRC discriminated against its employees.

“Regrettably, I have had the opportunity of dealing with [the Canadian Human Rights Commission] for over 30 years now. I am not surprised racism runs amuck inside there because, in individuals that I have assisted over the course of the last 30 years, that’s precisely what they and I have run into.”

The experiences of people like Coward have prompted law sector organizations to call for changes to Canada’s human rights system.

Both former Supreme Court justice Gérard La Forest and the United Nations have called on Canada to give Canadians direct access to the without having to go through the commission.

“We believe it is time to heed the advice of Justice LaForest and the UN. It is time to finally move to a direct access model federally. The current model has not and is not working for racialized Canadians,” said the Canadian Association of Black Lawyers (CABL) in a 2021 letter.

Almost 30 other organizations signed the letter, which was sent to Justice Minister David Lametti.

The Canadian Association Labour Lawyers (CALL) has called for similar reforms.

“Right now, the commission acts as a gatekeeper, and the commission has demonstrated that it needs to get its own house in order before it starts determining whether other people’s claims are meritorious,” said labour lawyer and member of CALL Immanuel Lanzaderas.

CALL also calls for the cap to be lifted on the sum of penalties the tribunal can impose. Currently, the maximum that can be awarded to victims is $40,000.

As calls for change grow louder, some are urging caution.

The Canadian Human Rights Commission was a key player in the early days of a landmark discrimination case that resulted in the federal government agreeing in principle to cover $40 billion in compensation for people harmed by Canada’s discriminatory child welfare system. The settlement also required the federal government to reform the system that tore First Nations children from their communities for decades.

Cindy Blackstock represents one of the groups that launched that human rights challenge. She said the commission played a key role in making sure First Nations children received justice.

“If you are a person who is discriminated against or are part of … a group that’s being discriminated against, there aren’t a lot of options for you to get justice,” said Blackstock, executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society.

“I think we need to be really careful about not introducing ideas that may have the unfortunate side effect of gutting our human rights system when we need it the most.”

Blackstock said the fact that the commission discriminated against its own employees is still “disturbing.” She said the human rights system needs leadership with a track record of treating employees and the public with dignity.

In a statement, the commission defended its model, which triages complaints before they move to mediation at the tribunal stage.

“The commission’s model supports access to justice by working with complainants to articulate their experiences in a way that meets the requirements of the law, including identifying systemic discrimination,” said Malischewski.

“Commission mediators work closely with parties to empower them to reach speedy resolutions of their own design. When cases are referred to tribunal, commission lawyers regularly represent the public interest throughout the process, from the tribunal all the way to the Supreme Court.”

Source: Human rights commission acknowledges it has been dismissing racism complaints at a higher rate