Good overview article by Aaron Wherry of CBC on diversity in government, both public service and political appointments. Some of my analysis quoted and used:

Campaigning in 2015, Justin Trudeau’s Liberals promised to “build a government as diverse as Canada.”

That job might’ve seemed nearly done on Day One. Of the 31 ministers sworn in on Nov. 4, 2015, 15 were, famously, women. Five ministers were visible minorities and two others were Indigenous.

A cabinet ratio of 48.3 per cent women, 16.1 per cent visible minorities and 6.5 per cent Indigenous comes close to matching a Canadian population that was 50.9 per cent women, 22.3 per cent visible minorities and 4.9 per cent Indigenous.

But a prime minister and his government are responsible for far more than a few dozen cabinet positions. The cabinet oversees more than 1,500 appointments, including chairs and members of boards, tribunals and Crown corporations, deputy ministers, heads of foreign missions, judges and senators.

On that much larger scale, progress has been made, but the ideal of a government that looks like Canada is still a ways off.

A new appointment process

When the government was sworn in, just 34 per cent of federal appointees were women, 4.5 per cent were visible minorities and 3.9 per cent were Indigenous.

Two years later, according to data from the Privy Council Office, 42.8 per cent of appointees are women, 5.6 per cent are visible minorities and 5.8 per cent are Indigenous.

In February 2016, the Liberal government announced a new appointment process for boards, agencies, tribunals, officers of Parliament and Crown corporations. It specified diversity as a goal and opened applications to the public.

According to the Privy Council Office, 429 appointments were made via that process through Dec. 5, 2017. Of those, 56.6 per cent were women, 11.2 per cent were visible minorities and 9.6 per cent were Indigenous.

A total of 579 appointments — including deputy ministers, heads of mission and appointments for which requirements are specified in law — were made through existing processes. Of those, 43.7 per cent were women, 3.8 per cent were visible minorities and 5.2 per cent were Indigenous.

“Mr. Trudeau has been more intentional on these issues than his predecessors and has made great progress in opening up the process. He has also clearly made great strides on gender,” says Wendy Cukier, director of Ryerson University’s Diversity Institute.

But, says Cukier, the government’s efforts toward transparency and equal opportunity need to be accompanied by “proactive outreach and recruitment as well as retention strategies” in order to “address some of the barriers historically disadvantaged groups have faced.”

Eleanore Catenaro, press secretary for the prime minister, says, “Our aim is to identify high-quality candidates who will help to achieve gender parity and truly reflect Canada’s diversity.”

She says, “We know there is more work to do to achieve these goals, and we continue to do outreach to potential qualified and diverse candidates to encourage them to apply.”

Rigorous reporting of demographic data across federal appointments could presumably drive change — or at least give the government something to answer for — but most of these numbers have not been made public.

“It is crucial that the government tracks, measures and reports on diversity in all areas,” says Sen. Ratna Omidvar, the founding director of Ryerson’s Global Diversity Exchange. “By doing so, we are able to see where we are making progress and where we need to improve.”

Beneath those top-line numbers, there are a few other points of reference.

According to Global Affairs Canada, the government made 87 heads-of-mission appointments — ambassadors, consul generals and official representatives — in 2016 and 2017. Forty-eight per cent were women and 13.8 per cent were visible minorities. There were no Indigenous appointees.

Senate and court appointments

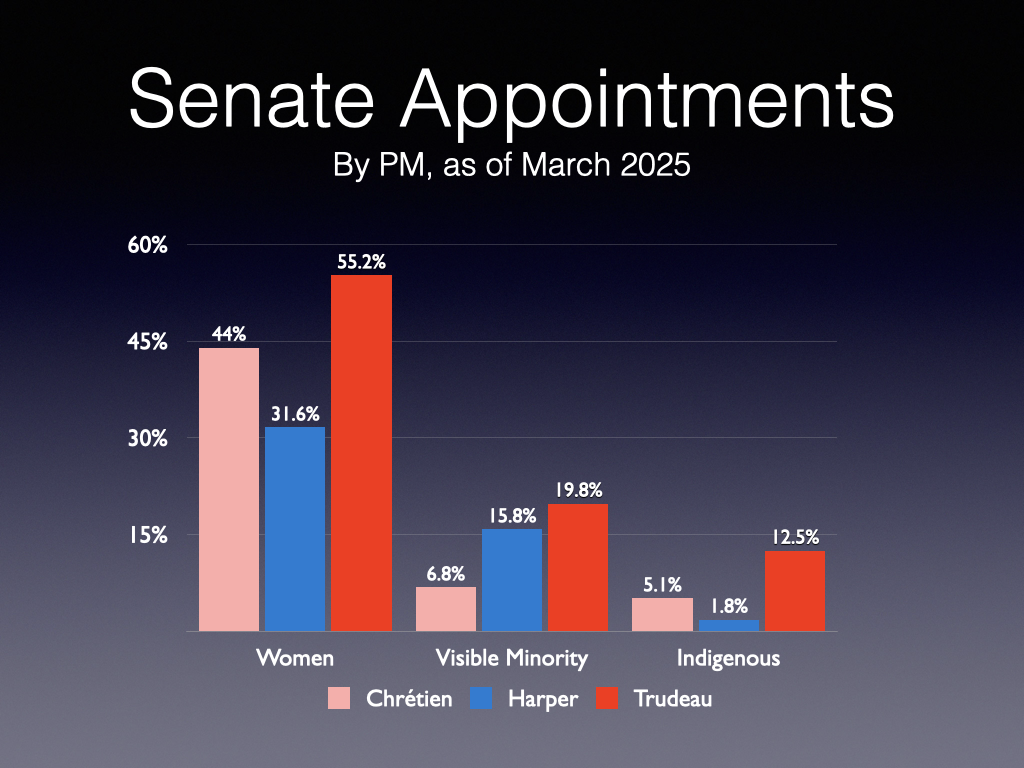

Andrew Griffith, a former official at the department of citizenship and immigration who has been tracking diversity in federal appointments, has counted 18 women, six visible minorities and three Indigenous Canadians among Trudeau’s 31 Senate appointments.

As a result of an initiative to track judicial appointees, the Office of the Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs has published a tally of court appointments from Oct. 21, 2016 through Oct. 27, 2017. Between those dates, 74 judicial appointments were made, of whom 50 per cent were women, 12.1 per cent were visible minorities and four per cent were Indigenous.

But that data also suggested the pool of candidates was limited: of the 997 applications received, just 97 applicants identified as a visible minority and 36 were Indigenous.

At some point, it might be charged that diversity is being inappropriately prioritized ahead of merit or competency — as Kevin O’Leary once alleged of Trudeau’s cabinet. But such suggestions assume that achieving diversity must come at the expense of merit.

Ideally, diversity would also amount to more than a numerical value.

3 benefits of diversity

Griffith, for instance, suggests three potential benefits of diversity in appointments: that it allows Canadians to see themselves represented in government institutions, that it brings a range of experience and perspectives to government policies and operations and that it reduces the risk of inappropriate policies (for example, an RCMP interview guide that asked asylum-seekers about their religious practices).

“It has been proven over and over that more diversity in the workplace leads to better outcomes,” says Omidvar, who is also pushing to tighten the standards included in a proposed government bill that would require corporate boards to report on diversity.

But the most profound impact could conceivably relate to Griffith’s first potential benefit. A nation that values diversity and pluralism might want its institutions to reflect those principles — and institutions that reflect those principles might advance the building of a multicultural society.

“It normalizes diversity,” Omidvar said of public appointments. “At this point, diversity is still sort of not the norm, which is why we focus on it.”