More coverage of declining public support for current high levels of immigration. Starting with the Toronto Star (arguably, there has been greater misinformation by the advocates of high levels of immigration than from those advocating caution):

A pair of new polls point to a continuing decline in Canadians’ support for immigration — findings one pollster describes as a “clarion call” for the federal government.

The two surveys were released Monday, ahead of the expected unveiling this week by Immigration Minister Marc Miller of the government’s latest immigration plan, which will set the number and composition of the various classes of permanent residents welcomed to Canada over the next three years.

The federal government’s current immigration plan, unveiled in 2022, aimed to bring in 465,000 new permanent residents this year, 485,000 in 2024 and 500,000 in 2025. The Immigration Department is on track to meet the 2023 target.

Over the past year, amid surging interest rates and the increasing cost of living, Canada’s high immigrant intake has been tied to the housing crisis as well as a strained health-care system and per-capita productivity.

The poll by the Environics Institute for Survey Research and Century Initiative found the number of respondents who agreed “immigration has a positive impact on the economy of Canada” has dropped 11 per cent from last year and reached its lowest level since 1998.

Lisa Lalande, CEO of Century Initiative, said the data is a “clarion call” for proactive economic planning, improved integration policies and investments in infrastructure such as housing in order to preserve the confidence of Canadians.

“Immigration makes us a more prosperous, diverse, resilient and influential country — but only if we do the work to grow well,” said Lalande, whose group advocates for responsible population growth.

The separate poll of 1,500 people by the Association for Canadian Studies and Metropolis Canada revealed similar trends. It found 57 per cent of respondents in Greater Toronto felt there are too many immigrants, compared to 41 per cent in Montreal and 49 per cent in Vancouver.

Respondents in Greater Toronto were also most likely to feel there were too many refugees admitted to Canada, with 55 per cent of them agreement with the statement, followed by 40 per cent among those from Montreal and 39 per cent of those from Vancouver.

“These surveys were indicative of a shift in sentiment around the numbers of immigrants coming to the country, a lot of which, I think, is connected to issues around housing,” said Jack Jedwab, president of the ACS and Metropolis.

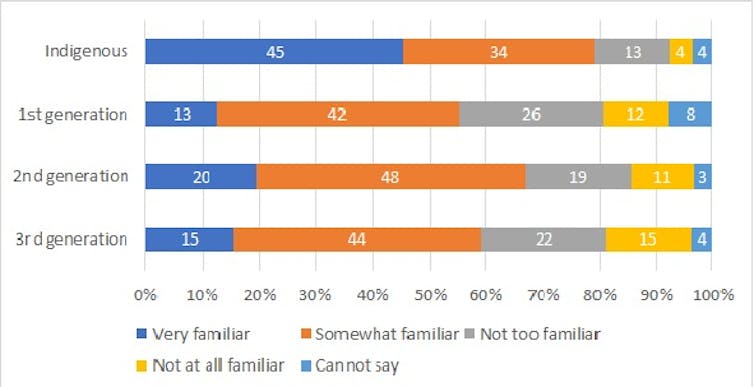

Those sentiments are fuelled in part by the lack of knowledge among Canadians of the country’s immigration landscape, he said.

Thirty-seven per cent of participants in the survey thought Canada received more than 250,000 refugees a year, when only about 76,000 were accepted. They also overestimated the number of permanent residents admitted to the country, with 27 per cent of people believing that Canada had already been taking in 500,000 newcomers a year.

The misinformation speaks to the need to better educate and inform the public about Canada immigration, Jedwab said.

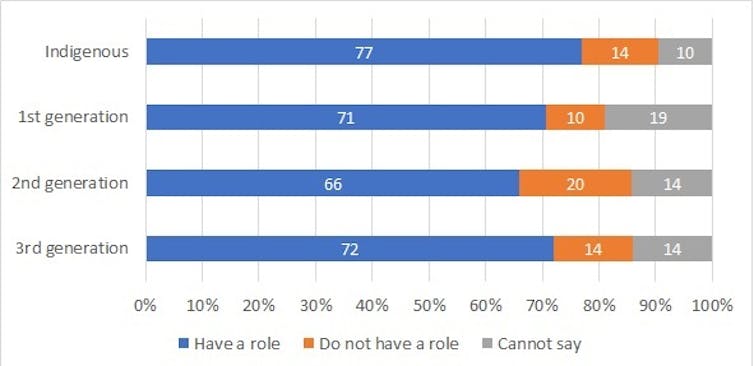

“Policymakers have to pay more serious attention to how we manage immigration and manage opinion around immigration,” he said. “They need to explain to people why immigration continues to be so vital to the future of our country.”

At an event on Friday, the immigration minister said discussions about the upcoming immigration plan were ongoing but hinted that reducing immigrant intake was not an option, even though he said he understood the public concerns.

“This is one of the most significant economic vehicles to our country, but we need to do it in a responsible way,” Miller told reporters. “The net entrance into the workforce is 90-plus per cent driven by immigration, so any conversation about reducing needs to entertain the reality that would be a hit to our economy.”

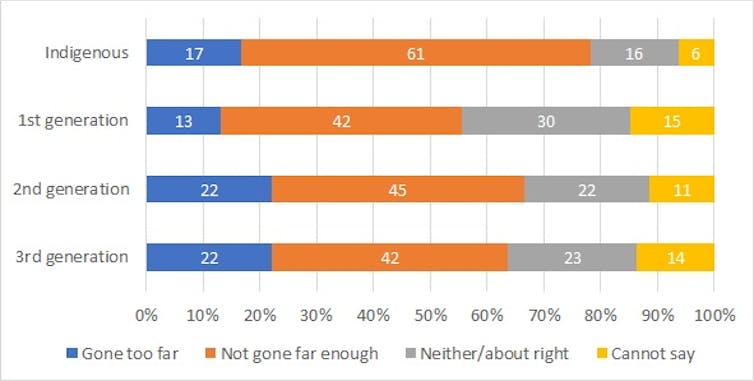

The Environics and Century Initiative report showed 44 per cent of Canadians said they were strongly or somewhat in agreement with the statement, “there is too much immigration to Canada,” up 17 percentage points from a year ago, the largest one-year change recorded on this question since the annual survey started in 1977.

It said those who agreed with this statement were most likely to cite concerns that newcomers may be contributing to the current housing crisis (38 per cent of this group give this reason) compared to only 15 per cent in 2022.

Respondents continued to identify inflation, cost of living, the economy and interest rates as the most important issue facing the country. Overall, just 34 per cent of people said they were happy with the way things are going in Canada, down 13 percentage points from last year.

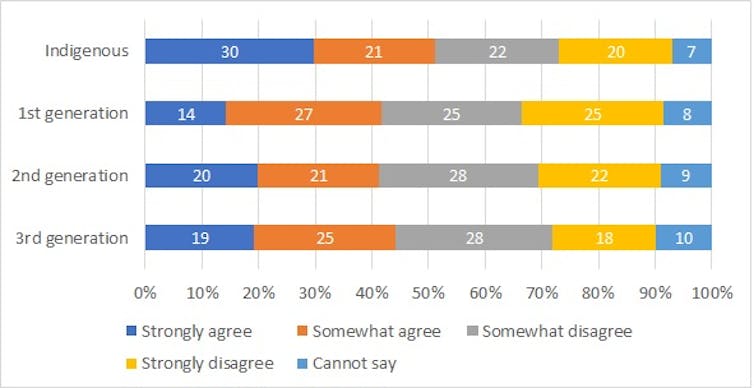

The silver lining is that the negative public sentiments toward immigration do not appear to have translated into Canadians’ feeling about immigrants themselves, the survey said.

Forty-two per cent of respondents said immigrants make their community a better place, compared to just nine per cent who believed newcomers make it worse, with the rest saying it makes no difference. Those with a positive view cited local diversity, multiculturalism as well as the role immigrants play in economic and population growth.

Of the various admitted classes of permanent residents, the respondents also want the federal government to prioritize those with specialized skills and high education, followed by refugees fleeing persecution and overseas families of Canadians.

Temporary foreign workers in lower-skilled jobs and international students were ranked the lowest, with only about one-third of people saying those two groups should be a high priority, the report found.

The 2024-26 immigration plan is expected to be tabled in Parliament on Wednesday.

L’appui aux cibles d’immigration actuelles est en chute libre. Entre 2022 et 2023, la proportion de Canadiens susceptibles de dire qu’il y a trop d’immigrants dans le pays a bondi de 17 points de pourcentage, ce qui vient renverser radicalement une tendance qui remonte à des décennies.

Quelque 27 % des Canadiens considéraient l’an dernier que « le Canada accueille trop d’immigrants ». Cette année, ils sont 44 % à affirmer une telle chose, une croissance record de 17 points.

Ces données sont tirées d’un sondage probabiliste en partie réalisé et financé par l’organisme Initiative du siècle, qui promeut l’idée d’une population de 100 millions d’habitants d’ici 2100.

« On a déjà vu des périodes où l’opinion restait en mouvement, mais là, c’est un saut. On peut dire que c’est du jamais vu », explique Andrew Parkin, l’un des chercheurs de cette étude. Il faut remonter au début des années 2000 pour observer une telle frilosité à l’égard des seuils d’immigration.

Ce changement d’opinion touche autant les Canadiens les plus fortunés (+20 %) que les immigrants de première génération (+20 %). Il touche aussi les partisans libéraux (+11 %), néodémocrates (+9 %) ou encore conservateurs (+21 %).

Économie et crise du logement

Ce n’est pas le malaise culturel que peuvent susciter les néo-Canadiens qui cause cette volte-face dans l’opinion publique, souligne le rapport. C’est plutôt le contexte économique difficile et la pénurie de logements qui fondent cette nouvelle réticence.

« Ça ne veut pas dire que les immigrants sont la cause de la crise du logement ou du manque de logements abordables, soutient Andrew Parkin. C’est plus : “Est-ce que c’est le bon moment pour avoir plus d’immigration étant donné qu’il y a une crise du logement ?” C’est une nuance. […] Le contexte économique touche tout le monde également. Ça touche aussi les immigrants, qui cherchent aussi à acheter une maison. »

Malgré tout, une majorité (51 %) de Canadiens rejettent encore l’idée que les niveaux d’immigration seraient trop élevés. Et ils sont très peu nombreux à voir l’immigrant comme un problème en soi.

« Certains disent qu’on utilise la crise du logement comme excuse pour se tourner contre les immigrants. Ce n’est pas ça. Le nombre de Canadiens qui disent que l’immigration empire leur communauté, c’est juste 9 %. Au Québec, c’est 4 %. »

Le Québec plus ouvert

Le Québec suit la tendance canadienne, mais demeure le territoire où le sentiment général reste le plus ouvert aux nouveaux arrivants. Environ un tiers (37 %) des Québécois considèrent que les immigrants sont trop nombreux, contre 50 % en Ontario et 46 % dans le reste du Canada.

La vision du Québec sur cette question a grandement évolué depuis les années 1990. Pas moins de 57 % des Québécois considéraient en 1993 que les immigrants « menaçaient la culture du Québec » ; ils ne sont plus que 38 % à avoir cette opinion aujourd’hui.

Le Canada a franchi cette année le cap des 40 millions d’habitants, en raison notamment d’un flux migratoire toujours plus important.