Interesting. Wonder if any of this is happening in Canada (apart from the Canadian Sikhs in British Columbia):

It was pitch-black in the early morning after the Washington region’s first snowfall, when the Nigerian farmer went to check on his crops. Olaniyi Balogun pushed open the fence, took two steps, then stamped his boot against the soil. He bent over the rows of kale and gently touched the underside of a palm-size, sprouting leaf.

“Hmm,” he grunted, frowning. Just like he thought — frozen.

Most farmers in the Maryland suburbs stop growing their crops by mid-January, but Balogun wants to stretch out the season as far as he can. His wife says it’s because he’s a workaholic; he disagrees. In the rural towns outside Akure, the city in southwestern Nigeria where he was born, people farm year-round.

“For me, this is the only thing I know how to do,” said Balogun, 53, a stocky man with a deep, steady voice. Every time he steps out onto his farm, he said, he remembers himself as a boy, leaping off a crowded pickup truck into the cornfields, slingshot in hand.

“This is what makes me happy.”

Agriculture was once the driving economic force of Montgomery County, now a booming suburb of 1 million people. But after World War II, rapid industrialization drew residents and resources away from the land, leaving just several hundred farmers in what is now the county’s protected 93,000-acre agricultural reserve.

As the county’s demographics change, another shift is underway. Immigrants, many of whom grew up farming in their home countries, are taking over small pockets of the land — part of what advocates say is a national trend that is most pronounced in West Coast states such as California and Washington.

In the United States, farmers have been — and are — predominantly white and male. A third of them are over 65, and as they march toward retirement, many struggle to find successors, contributing to a crisis within the industry that has seen rises in bankruptcies, loan delinquencies and suicides.

From New York’s Hudson Valley to California’s Central Coast, public and private organizations are trying to connect immigrants with the resources they need to start their own farms or cultivate land owned by others, hoping to infuse the industry with new energy and traditions.

The U.S. agriculture census does not track farmers based on national origin, but judging by its data on race, the growth of immigrant farmers seems likely, experts say. From 2007 to 2017 (the most recent year the census was conducted), the number of farms with Hispanic producers grew about 30%, from 66,000 to 86,000. Those who study the census note that since many land-leasing contracts happen informally, these figures may undercount the number of foreign-born farmers who are bringing their agricultural traditions to U.S. shores.

In her recent book “The New American Farmer,” Syracuse University professor Laura-Anne Minkoff-Zern says immigrant farmers often introduce new crops and their own, more sustainable farming practices — complementing a growing U.S. “food movement” that urges consumers to take back control of what they eat.

Some immigrant farmers in Maryland have become their neighborhood’s local producers, reviving fading relationships among buyers, farmers and landowners.

“These farmers, their heart and soul are in the land,” said Caroline Taylor, a Maryland farmer and the head of the nonprofit Montgomery Countryside Alliance. “It’s something people miss.”

A love match service: land + farmer

The alliance runs a program, called Land Link, that matches potential farmers with landowners who don’t want to farm but want to keep their land active. The goal, Taylor said, is to revitalize the agricultural reserve and in turn fend off developers hungry for the land.

Since it started in 2011, the Land Link program has helped to lease out nearly 500 acres. It has gained more momentum in recent years, Taylor said, in part because of increasing demand from immigrant and minority farmers, who constitute the majority of applicants. Alliance staff members receive a growing number of inquiries each week on the program, Taylor added, some from people not even in the country yet.

Before he moved to the United States, Balogun ran his own farm in Nigeria that spanned more than 120 acres. In 2016, he married Tope Fajingbesi, a self-described “city girl” who left Lagos in the early 2000s to study, and later settle in College Park as a lecturer at the University of Maryland. They agreed that he would join her if — and only if — he could farm. But in wealthy Montgomery, buying land, even renting, seemed impossible.

“I said to him, ‘Yes, of course we will do it,’ but inside, I thought, ‘Oh my God, there’s no way,’ ” Fajingbesi, 42, recalled. “What was the plan? I don’t know. We had no plan.”

When Land Link first matched them with landowners Dorothy and Brad Leissa, Fajingbesi crunched the numbers. “$500 a month,” she told her husband. That’s all they could shell out. At an introductory meeting, the Nigerian couple nervously asked the Leissas how much it would cost to rent the acre of land around the their 19th-century farmhouse. When the landlords asked for a dollar, Fajingbesi thought she had misheard. One dollar, the Leissas repeated.

“We’re happy to share,” said Dorothy, a soft-spoken schoolteacher. “Really, we’re happy to let them use it.”

Slowly, Balogun began to build up Dodo Farms, spending 11 — sometimes 12 — hours at the site each day. When he harvested his first tomatoes, he brought a bag to the Leissas’ farmhouse at the top of the hill. At Thanksgiving, he turned up at their door with a 25-pound turkey.

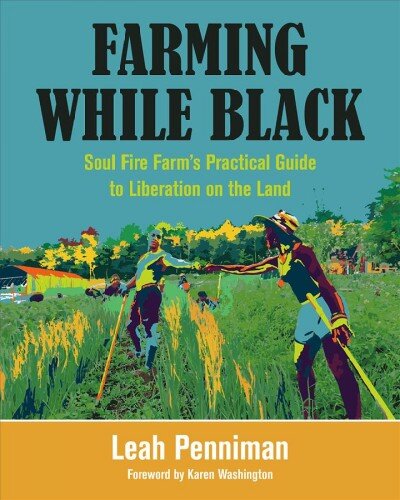

“A lot of the folks in the sustainable farming world get a lot of information through these conferences and sort of assume that … it’s either ahistorical or originated in a European community, which is an injustice and a tragedy,” Penniman says.

“A lot of the folks in the sustainable farming world get a lot of information through these conferences and sort of assume that … it’s either ahistorical or originated in a European community, which is an injustice and a tragedy,” Penniman says.