Largely reflects the interests of education institutions and their financial pressures as much as concerns over differential treatment (given that immigration is inherently “discriminatory,” the question is more are their legitimate reasons and evidence to justify that discrimination):

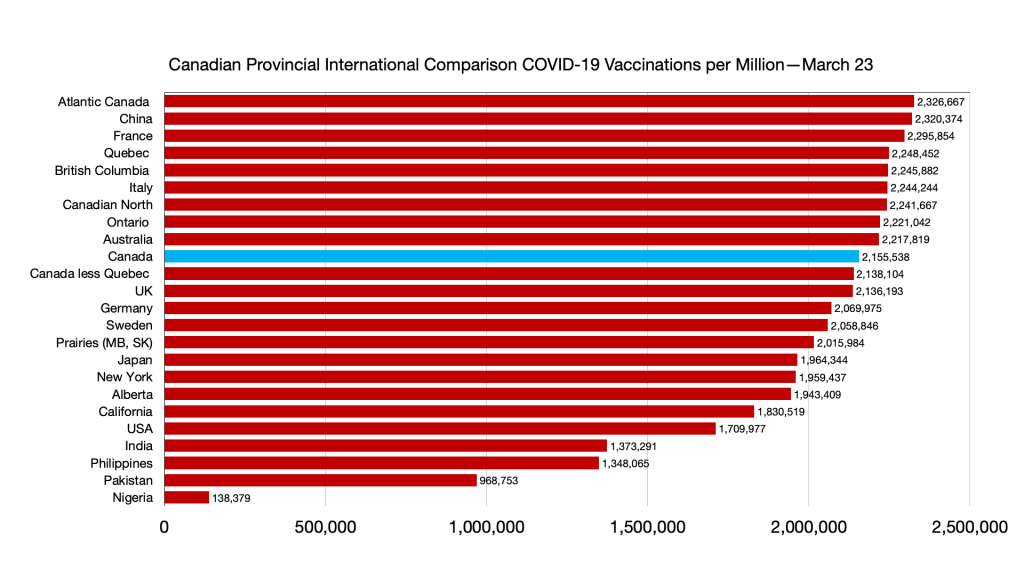

In the five years between 2018 and 30 April 2023, officials at Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada reportedly rejected 59% of the visa applications from English-speaking Africans and 74% from French-speaking Africans seeking to study in Canada’s colleges and universities.

In 2022, the disapproval rates were 66% for applicants from French-speaking African countries and 62% for applicants from English-speaking African countries.

Besides the higher rejection rate for francophone African students, the stats show a massively higher rejection rate for African students compared to students from Western countries. Refusal rates for Great Britain, Australia and the United States were 13%, 13% and 11%, respectively, while for France the refusal rate was 6.7%.

‘A certain rate of racism exists’

Referring to hearings held in 2022 by the House of Commons Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration (SCCI) during which Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) admitted there was a problem, Etienne Carbonneau, director of research and support for internationalisation at Université du Québec in Québec City, said: “Let’s put it bluntly, we think there is a certain rate of racism that exists [in IRCC].

“By this I mean negative prejudices against, particularly, French-speaking African populations. When you look at IRCC’s responses, basically, the immigration officers who process the permit application files seem to be saying that they don’t believe the students.”

Both Carbonneau and Daye Diallo, senior economist at the Montreal-based Institut du Québec, underscored that while the high refusal rate of English-speaking Africans can also be attributed to racism at the IRCC, the impact on English universities such as McGill University in Montreal, or those in Ontario or elsewhere in the country, is not as severe.

“In Ontario, it [the rejection rate] is more than 50%. Serious too, but it is higher in Quebec. And because Quebec speaks French, the recruitment pools are more limited. In Ontario there are many students who come from Asia and English-speaking countries,” says Diallo, co-author, with Emna Braham, the institute’s executive director, of the study, “Portrait de l’immigration temporaire: attraction et rétention des étudiants étrangers au Québec”.

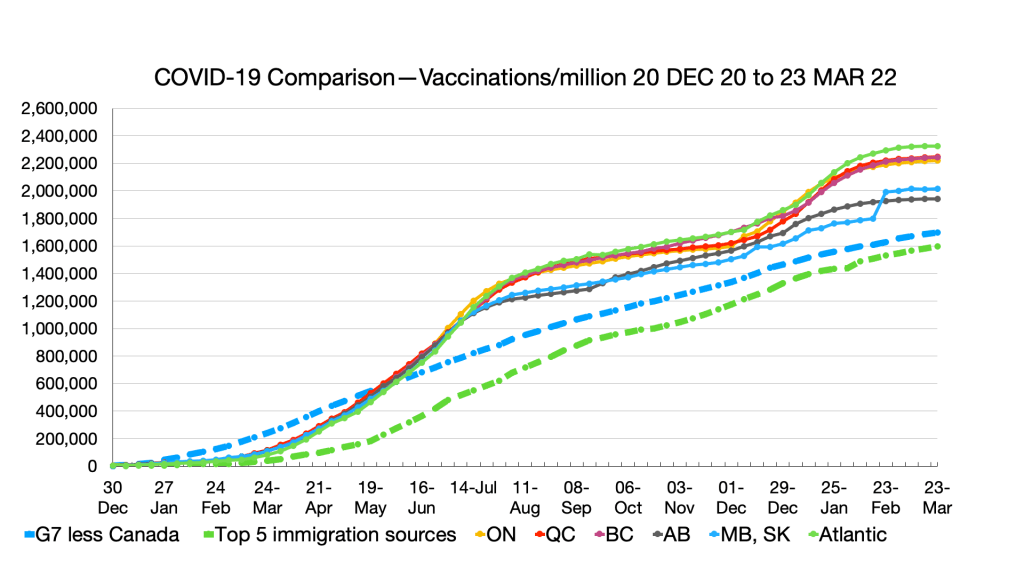

“We cannot go to India or China because Indians and Chinese are looking for training in English,” Carbonneau explained. “If I were at McGill University or University of British Columbia, and I saw that it was getting difficult on the Indian side [ie, recruiting from India], I would look to other markets. I don’t have that opportunity [recruiting for a French university].

“The potential for growth is really in French-speaking Africa, but this potential is cut off by the practices of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. Presently, some 50% of French speakers worldwide live in African countries; by 2050, the continent will account for 50% of the world’s population growth.”

SCCI report evidence

The report of the Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration (SCCI), published in May 2022, titled Differential Treatment in Recruitment and Acceptance Rates of Foreign Students in Quebec and in the Rest of Canada, found evidence of racism both in the internal workings of the department and among IRCC’s visa officers vis-à-vis African applicants for study visas.

This evidence was contained in a report of a survey of IRCC conducted by the polling firm Pollara Strategic Insights following the international protests against the murder of George Floyd by members of the Minneapolis (Minnesota) police department in March of 2020, which sparked the Black Lives Matter protests.

Racialised respondents to the IRCC survey told Pollara that they “considered racism to be a problem in the department”, which, in its response to the report, IRCC acknowledged.

Pollara was told that some immigration officials referred to certain African countries as “the dirty 30”. Nigerians, the investigators were told, were considered “particularly untrustworthy”.

According to the SCCI, IRCC “acknowledged that due to the nature of its mandate to promote a strong and diverse Canada, it must hold itself to the highest possible standards so that the programmes, policies and client services are free from any racial bias”.

IRCC policy

IRCC reiterated this policy in an email that said, in part: “The Government of Canada is committed to the fair and non-discriminatory application of immigration procedures. We continually evaluate data and make concerted efforts to address the results and the differential strategies in order to improve our approaches so that we can overcome these issues.”

The email further explained: “The strategic review of the immigration policies and programmes will enable us to identify and address the issues relating to rejections and the International Student Program will be informed by this exercise.”

Among the steps IRCC has taken is the creation of a task force dedicated to the “elimination of racism in all its forms at IRCC”. This requires IRCC staff, including middle and senior managers, “to take mandatory unconscious bias training which is tracked”, and evaluate “potential bias entry points in policy and programme delivery [ie, deciding on visa applications]”.

As of May 2022, IRCC had “nearly two dozen projects under development to reduce and eliminate racial barriers – with a large focus on … African clients, due to the fact that this region historically faces longer processing times and lower approval rates”.

Nigerian students deemed ‘particularly untrustworthy’

While some IRCC staff considered Nigerians to be ‘particularly untrustworthy’, critics, including the University of Calgary’s Assistant Professor of Artificial Intelligence and Law Gideon Christian, who is also president of African Scholars Initiative, told the House of Commons committee that the 2019 pilot project, Nigerian Student Express (NSE), discriminated against Nigerians.

Pointing to documents he had obtained via an Access to Information and Privacy request, Christian showed that irrespective of whether the NSE improved processing times for Nigerian students by giving them the option to use a secure financial verification system, it discriminated against these students.

The NSE required Nigerians to provide different and more onerous financial data than did students from other countries that were part of the Student Direct Stream (SDS), Christian said.

Unlike students in the other 15 countries included in the SDS, such as China, Vietnam, Senegal, Brazil and Colombia, Nigerians seeking to study in Canada had to produce a bank statement showing that they had the equivalent of CA$30,000 (US$22,600) in their account for at least six months in the last year.

While testifying before the committee, Sean Fraser, minister of immigration, refugees and citizenship of Canada, defended the CA$30,000 figure, saying that it was fair because it did not include living expenses.

“The issue is that we don’t necessarily have financial partners on the ground in Nigeria, so having proof of funds of CA$30,000 is more equitable when you look across the requirements in other countries, where you have not only [the requirement to show] CA$10,000, but also the proof of funds to cover the cost of an international student tuition.”

In his testimony, Christian dismissed Fraser’s claim, noting that a “Nigerian is required to show proof of funds that are three times more than those of other SDS countries, and yet, when this applicant overcomes this high burden of proof, most of the study visa applications from Nigeria are still refused”.

Christian also told the SCCI that since all colleges and universities exempted Nigerians from English-language proficiency tests, “the language proficiency requirement imposed by the visa offices … exudes stereotypes and racism”.

SCCI Recommendation 4

The SCCI’s Recommendation 4 called for IRCC to reconsider the financial reporting requirements imposed on Nigerians and for IRCC to “remove the English-language proficiency required for Nigerian students”.

As with Canada’s English universities, French universities in Quebec recruit international students for a number of reasons. Carbonneau began by noting the importance of universities internationalising their student bodies.

“The career of a researcher who is from Quebec will involve collaborations with people who have been trained abroad and who have worked abroad. The integration of international students into our university programmes means that our Quebec students will have contact with people from other countries. They will be made aware of international issues and the issues of intercultural work and the taking into account of intercultural issues.

“We understand how the presence of international students, particularly at the graduate level, makes it possible to develop links between researchers and students that will be maintained over time.”

Recruiting in French-speaking Africa

International students contribute CA$22 billion (US$16.6 billion) to the Canadian economy and support more than 218,000 jobs, the SCCI heard. The portion of these funds spent in Quebec is part of the third reason Quebec’s universities recruit in French-speaking Africa. The other part is that the 217,660 French African students in the province’s colleges and universities help keep these institutions economically viable.*

The tuition for Quebec residents at the province’s French universities is approximately CA$6,000; international undergraduates payCA$30,000 more. Each international student also contributes some CA$15,000 to the province’s economy in living costs.

Since Quebec universities receive grants on a per student basis from the provincial government, for universities international students mean larger government grants.

According to Carbonneau: “We need students for the vitality of several of our university programmes. Quebec universities are funded per student, so when we have students, we have funding.”

Ontario’s universities, too, it should be noted, are hungry for international student fees. For the 2021-22 academic year, for example, the 22,728 international students at the University of Toronto, for example, paid on average CA$59,320 in tuition and fees, or a total of over CA$1.3 billion.

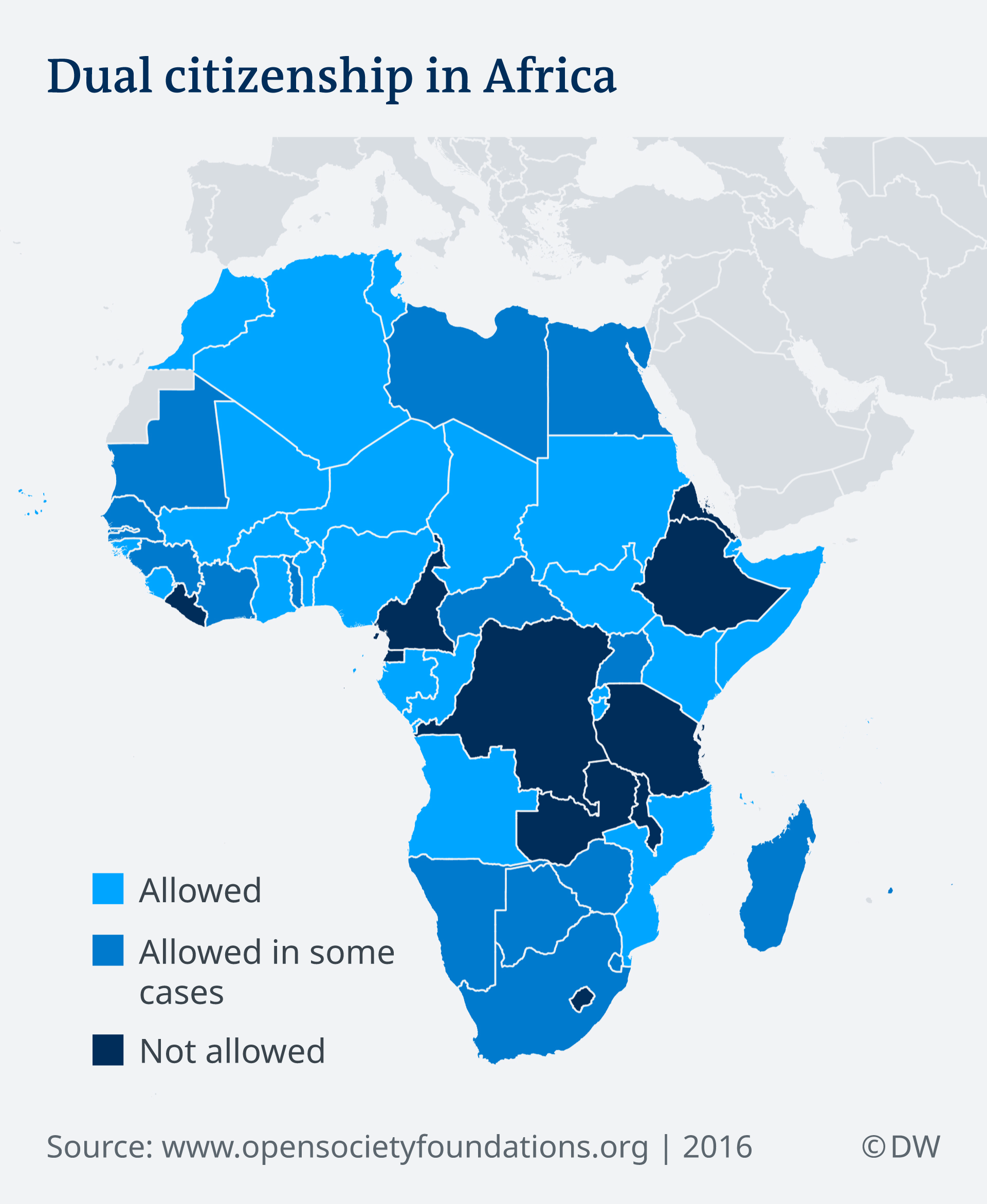

Recruiting university students from French Africa is also part of the government of Canada’s commitment to ensuring that approximately 72,000 of the nation’s immigrant target of 500,000 are French speaking. This policy was put in place to ensure that the percentage of French-speaking Canadians did not fall below the present 22.8%of the nation’s population of 40 million.

Although Fraser told the SCCI that “international students are excellent candidates for permanent residency” and that Canada has “increased our target efforts overseas to promote and attract francophone students and immigrants to Canada”, the committee heard of a number of roadblocks that prevented French African students from studying in Canada.

At the hearings, Alain Dupuis, executive director of the Fédération des communautés francophones et acadienne du Canada (Canadian Federation of Francophone and Acadian Communities), stated that irrespective of the government’s immigration goals, “we are closing the doors to them”.

Investment certificate roadblock

Denise Amyot, president and CEO of Colleges and Institutes Canada, told the SCCI that one of the main roadblocks is a requirement created, not by IRCC policy, but by its visa officers: the guaranteed investment certificate to demonstrate financial sufficiency and SDS.

While this certificate may have streamlined the application process, it ignored the fact, Amyot told the SCCI, that the banking systems “in certain countries are not as well developed, and students rely more heavily on family networks in ways that may seem atypical from a Canadian cultural lens”.

Referring to the cases for which he knew IRCC’s reason for denying the application for a study visa, Diallo told University World News: “The reason in these situations is that the student does not have enough real estate; he does not have a house in his country of origin.” He then asked, pointedly: “How can an 18 year old own buildings?”

The guaranteed investment certificate is more than a proof of financial resources, Diallo further explained. It serves as a proxy for the applicant’s attachment to his or her home country: ie, as proof that he or she plans to return to their home country.

Similarly, applicants have been denied study visas because they have not shown that they have enough family in their home countries, or that they have not established a travel history that shows that they have left and returned to their home country.

This is a requirement that one brief to the SCCI mocked by asking” “How many kids of the age 15-20 years old from other countries have travelled out of their shores at such a young age? What counts as sufficient travel history? This remains unclear,” says Carbonneau.

For his part, Diallo says: “There are reasons like that that are given. But they are ‘reasons’ which, in our opinion, are not necessary. [For] these reasons, the official can say that he believes the student will not return home. But these are not facts. There are no statistics that say that African students are more likely to stay here illegally when their visas expire.”

Residency roadblocks

Notwithstanding Fraser’s statement that “international students are excellent candidates for permanent residency”, the very document applicants for study visas must fill out puts them in a ‘catch-22 situation’ with regard to what’s called ‘dual intent’, says Shamira Madhany, managing director and deputy executive director at World Education Services, told the parliamentarians studying the issue.

Canada’s Immigration and Refugee Protection Act allows for international students to apply for permanent residency upon completion of their studies if “the officer is satisfied that they will leave Canada by the end of their period authorised for their stay” and wait outside Canada for their permanent residency to be granted.

However, in practice, one witness told SCCI: “If a student has the misfortune to check that box, their chances of getting a visa are nil … The authorities believe that they really do not intend to study in Canada, and they want to stay in Canada.”

According to Carbonneau, this situation is absurd.

“A student who comes to study with us with the intention of immigrating, which is deemed desirable by our government in Quebec [the lone province to issue its own study document accepting the prospective student], is using his studies, a bachelor degree or a masters degree or a doctorate, to integrate into Quebec or Canadian society – and then immigrate.

“For us it is desirable. But for the Government of Canada, I think the second most frequent response is that the application is refused because the Canadian government is not convinced that the student will return to his country after graduation.

“It’s really absurd because on the one hand Canada really needs qualified immigrants. We also need qualified French-speaking immigrants. But, on the other hand, we tell them once they graduate our expectation as a Canadian government is that you return home.”

Reform required

In his appearance before the committee, Fraser admitted the system needed reform but pushed back against critics by saying that Canada “need to prevent a lot of students coming with the purpose of staying permanently by claiming asylum, for example, when we have different streams for people who are coming for purposes other than studying”.

While Recommendation 15 does not expressly refer to the minister’s statement, by implication it rebuked him by calling on IRCC to clarify the dual intent provision of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, “so that the intention of settling in Canada does not jeopardise an individual’s chances of getting a study permit”.

Organisations and individuals involved in recruiting in Africa are concerned that Canada’s high rate of refusal of study visa applicants is hurting the country’s reputation in Africa. Amyot told the SCCI that he had heard of students who waited months for decisions only to find out that their study permits had been rejected “often for unclear and unfounded reasons”.

“We live in a world where the competition to attract the best brains is very important. Canada cannot afford to have these difficulties. Canada must work to reduce refusal rates from French-speaking African countries that have students who want to come to Canada,” said Diallo.

“We have a poor image internationally because Canada does not grant visas and the reasons why Canada does not grant visas are not the right reasons.”