Ukraine: How citizenship and race play out in refugees’ movements in Europe

2022/03/14 Leave a comment

More nuanced explanation that in most articles:

As millions of refugees flee Ukraine as a result of the Russian invasion, one question that has been raised is: Why have Ukrainians been welcomed into eastern Europe, unlike Syrians, Iraqis, Afghans and Eritreans? Is it because they are white?

Criticisms imply that the European Union treats refugees from the Global South differently, and that such treatment is based on race. Critics also highlight that Romania and Poland’s hospitality to Ukrainians stands in stark contrast to their past reluctance to accommodate refugees from Africa and the Middle East. Al Jazeera looks at the treatment of Black and Indian refugees at the Polish border.

Yet hasty interpretations that single out race as the primary force in refugee favouritism simplify geopolitical realities. They also ignore the EU legislative framework that produces categories of refugees based on nationality and citizenship.

Europe rests on a hierarchy of nations, with older EU members at the top of the pile followed by new members, and then countries being considered for membership in the EU. At the bottom of the pile is everyone else.

Geopolitics play a role

Commitments to welcoming one million Ukrainians to Polandand 500,000 to Romania are linked to these countries’ geographical proximity to the Ukrainian border.

Refugees usually head to the closest safe place. Think of the Syrian war: neighbouring Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan resettled the largest number of Syrians. Turkey hosts close to four million, Lebanon over 800,000 and Jordan close to 700,000.

Similarly, more than half of Eritrean refugees are in neighbouring Ethiopia and Sudan. Bangladesh also hosts the majority of Rohingya refugees from neighbouring Myanmar.

Ethnic composition and regional labour market flows also play a role. Poland is the primary EU destination country for Ukrainian migrants. By the end of 2020, a record number of a million and a half Ukrainians had migrated to Poland for work.

In Ukraine, close to 160,000 people are ethnic Hungarians, and over 150,000 are of the Romanian minority. The Union of the Ukrainians in Romania is an ethnically based political party with a seat in the national parliament.

Ukrainians regularly cross regional borders for personal reasons, such as accessing medical care or visiting family.

Pre-existing affinities

Eastern Europe shares a common Soviet history and after the end of the Cold War in 1989, an anti-Russian sentiment. With the fall of the Berlin Wall, most eastern European states rejected communist ideas as being Russian-centric. Integration into the West and the adoption of liberal ideas of freedom, free market and democracy, have become synonymous with opposing Russian neo-imperialism.

Solidarity based on a similar history of oppression is common across the former Eastern Bloc countries (the Soviet Union, Poland, East Germany, Albania, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Romania, Czechoslovakia and Hungary). A shared memory of Russian aggression makes the pain of Ukrainians more intelligible to other eastern Europeans.

Linguistic similarities between Ukrainian and Polish make Poland more accessible to Ukrainian migrants. Both languages are Slavic and have long influenced each other. The Polish and Ukrainians close to the border largely understand what each other is saying.

Most countries from the former Eastern Bloc are Christian Orthodox. Not only is Christian Orthodoxy intertwined with national identity but Orthodoxy has also flourished since the fall of Communism. In Ukraine, about 39 per cent of the population self-identified as Orthodox in 1991 — by 2015, the number had doubled.

Ukraine’s position

Ukraine is not a member of the EU, but it is a signatory to the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) and the 2014 EU-Ukraine Association Agreement.

The 2014 Association Agreement was key in defining Ukraine as a European country with shared common history and values. It also paved the way for granting Ukrainians visa-free access to the Schengen Area, which comprises all the EU members except Ireland, as well as Norway, Iceland, Switzerland and Lichtenstein, for up to 90 days.

Both agreements outline the foreign policy expectations of countries on the path to EU integration. These agreements legally produce different categories of migrants. Ukrainians are on the path to integration into the European labour market, unlike third-country nationals, defined as non-citizens without the right to free movement in the EU.

Through a budget of 15.4 billion euros, the ENP supports economic and social reforms for neighbouring countries of the EU including Algeria, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Egypt, Georgia, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Moldova, Morocco, the Palestinian Authority, Syria, Tunisia and Ukraine.

Since 2014, the ENP has funnelled more than 200 million eurosto help Ukraine’s path to EU integration. Ukraine has received over 17 billion euros in grants and loans, inclusive of financial supports for the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fortress Europe

With central and eastern European member states joining the EU in 2004, 2007 and 2013, eastern Europe has became the bordering outskirts of the EU. And so recent refugee flows have to be managed in the peripheral east, now tasked with militarizing their borders and keeping refugees out.

In contrast to the warm welcome granted to Ukrainian refugees, Poland has recently let Iraqi and Afghani refugees freeze to deathat its eastern border. It was the EU that tripled the border management funds to Latvia, Lithuania and Poland to reduce access to asylum, and increase border push-backs and detentions.

Citizenship or race?

The mistreatment of foreign nationals fleeing Ukraine has been attributed to race.

“Black people” and “African students” are terms interchangeably used to describe those being held back at borders or being prevented from boarding evacuation buses.

Ukraine has continued the former Soviet tradition of regularly recruiting Global South students within the medical field. India, Morocco, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, Nigeria, China, Turkey, Egypt, Israel and Uzbekistan are the top 10 countries of origin for international students in Ukraine.

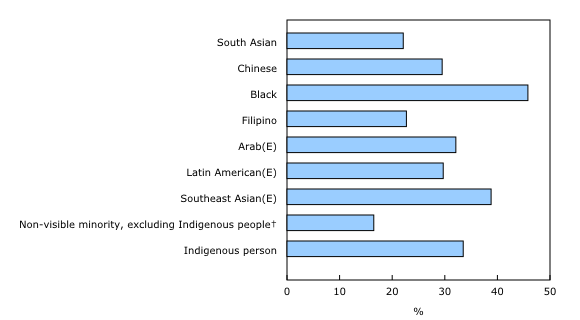

Much of eastern Europe is made out of racially homogeneous countries, where non-citizens are often visibly non-white. Using a racial lens to understand how borders respond to the attempts of international students to cross them diverts attention from citizenship regimes in allocating rights.

It also minimizes the larger problem at hand — the precarious status of temporary residents, including international students, who inhabit a marginal position by bureaucratic design.

Citizenship becomes the primary basis of exclusion. It is a related phenomenon that citizenship gets descriptively associated with race.

We do not intend to legitimize the racist and discriminatory coverage that has surfaced in relation to the Ukrainian refugee crisis.

Race does matter in refugee favouritism. But the opening of refugee corridors to Ukraine’s neighbours has little to do with race and more to do with geopolitical and citizenship regimes that determine freedom of movement within Europe.

Source: Ukraine: How citizenship and race play out in refugees’ movements in Europe