March blogging break

2026/02/28 Leave a comment

Back in April.

Working site on citizenship and multiculturalism issues.

2026/02/28 Leave a comment

While I largely disagree with the recommendations, good to have this data analysis on the impact of these preferences:

…Key findings include:

• In nine of 14 schools, the non-racial-minority, or non-Black, non-Indigenous applicant group had the lowest acceptance rates. Even among the five remaining schools where the “Discretionary” and “Black” applicant racial groups had the lowest acceptance rates, those rates were much higher than if the applicants from these two groups had been required to compete against all applicants, regardless of race.

• Thirteen schools (with two exceptions for LSAT-specific analysis) admitted fewer non-racial-minority or non-Black, non-Indigenous applicants than would have been the case had they selected applicants according to their top-ranked academic performance.

• Further analysis showed that 216 applicants or 10 per cent were admitted with lower grades out of 2,150 medical and law school first-year students who were all from designated racial minority applicant groups. A similar admission pattern was also observed for LSAT/MCAT scores, with 132 racial minority applicants admitted with lower scores, or 6.1 per cent of the total number of admitted students. This analysis indicates that race-based admission policies result in the admission of academically weaker students.

• In every school that provided admissions data, the non-racial-minority or non[1]Black, non-Indigenous applicant groups experienced the highest number of rejections despite higher academic scores than the admitted applicant from other racial groups with the lowest academic score from their group.

• Most medical schools and many law schools refused to release their race-based application and admission data at all. This lack of transparency raises serious concerns about accountability in publicly funded institutions.

The implications are troubling. Institutional racism potentially erodes fairness and undermines public confidence in our standards for medical and legal education. Such racism is also remarkably resistant to scrutiny – operating behind policies that limit access to basic admissions data.

These findings give some specificity to broader concerns about DEI in Canadian universities and colleges, where critics have raised alarms about the growth of DEI bureaucracies, opaque hiring policies, and admission practices that prioritize group identity over merit.

Canada also stands out internationally. University officials in Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands reported that race is not considered in admissions decisions for medical or law schools.

Policy recommendations to address the racial segregation and discrimination identified in this report include:

• Provincial governments should prohibit the use of race as an admissions criterion in medical and law schools.

• To restore academic rigour, these schools should rely exclusively on objective measures such as the MCAT, LSAT, and required prerequisite coursework. Provinces should consider suspending funding to medical and law schools that continue to factor race into admissions decisions.

• In addition, provinces that continue to consider race in medical and law school admissions should be required to publicly release race-based application and admission data using consistent, transparent measures of discrimination, preferably measures similar to the measures used in this study. Without this disclosure, governments cannot effectively oversee or correct the disturbing trend of racial discrimination that threatens the overall academic strength of our medical and law students.

Recent public debates in Canada, including high-profile campus protests, faculty resignations over DEI mandates, and legislative scrutiny of “equity hires,” reflect growing concern that universities are straying from their core missions under the banner of DEI. Rather than sorting applicants by racial category, universities should focus on ensuring that all prospective students, regardless of race, have the academic preparation needed to compete fairly. This includes access to tutoring, frequent testing, and meaningful academic feedback well before the application stage….

Source: Discrimination by design? Race-based admissions in Canadian medical and law schools

2026/02/28 Leave a comment

Interesting research and wonder whether any of those involved had a sense of how their work would be used or was it more a case of wilful blindness and complicity:

Bookbinders and restorers in the 1930s and ’40s used their craft to help the Nazi regime create a database that was used to persecute and kill Jews and others who were deemed racially impure, a British researcher has found.

Key to building this database were church, civil and synagogue records, which were often hundreds of years old and damaged beyond legibility when the Nazis came to power in 1933.

By tasking professionals with cleaning up these documents, which held information about millions of people, the Nazis gained access to generations’ worth of material — which they used to target specific population groups, the new research shows.

The findings are the result of more than two decades of work by Morwenna Blewett, an expert in conservation history.

She was working as a conservation fellow at the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts in 2004 when a question came to her: What had happened to the art restorers who did not flee Nazi Germany during World War II?

She pondered the question while sorting through an old filing cabinet in the museum’s basement — where, as she recalled in a book published this month, “Art Restoration Under the Nazi Regime: Revelation and Concealment,” the “warm, dark air smelt faintly of cigarettes, coffee and engine oil.”

Soon, she had expanded on her query: “How did the Nazi regime intend to use conservation and restoration to achieve its aims?”

The answer, she discovered, was that paper restorers and bookbinders in Nazi Germany had helped the regime track down people’s Jewish ancestry by conserving and cleaning up old records from churches, as well as from synagogues and civil registers.

Dr. Blewett said that, by publishing her book, she hoped to shed light on this part of the Holocaust, which she called “one of the longest and most insidious of all National Socialism’s projects to exploit the field of conservation and restoration.”…

Source: How Bookbinders Used Old Records to Help the Nazis Find Their Victims

2026/02/27 Leave a comment

Concrete impact:

« Il y a effectivement 4 démissions et 8 ruptures du lien d’emploi associé au projet de loi 94. Les organismes publics comme les centres de services scolaires sont tenus d’appliquer celle-ci », a indiqué Mélanie Poirier, porte-parole du CSSMI, dans un courriel adressé à La Presse. Nos autres questions sont restées sans réponse.

Selon Annie Charland, présidente du Secteur soutien scolaire de la FEESP-CSN, toutes les personnes qui ont ainsi perdu leur emploi étaient des surveillantes ou des éducatrices en milieu scolaire. Toutes ont refusé de ne plus porter leur voile.

« Pour ces femmes, c’est une énorme déception », souligne Annie Charland, en entrevue avec La Presse.

Elles ont étudié là-dedans et on leur enlève la dignité de pouvoir gagner leurs vies.

Selon des documents transmis par la CSN à La Presse, le CSSMI a envoyé fin janvier une note à tous les membres de son personnel rappelant les nouvelles obligations légales encadrant le port de signes religieux, à la suite de l’adoption du projet de loi 94, le 30 octobre dernier….

“There are indeed 4 resignations and 8 terminations of the employment relationship associated with Bill 94. Public bodies such as school service centers are required to apply it, “said Mélanie Poirier, spokeswoman for the CSSMI, in an email sent to La Presse. Our other questions remained unanswered.

According to Annie Charland, President of the School Support Sector of the FEESP-CSN, all the people who lost their jobs as a result were school supervisors or educators. All refused to no longer wear their veil.

“For these women, this is a huge disappointment,” says Annie Charland, in an interview with La Presse.

They studied there and they are deprived of the dignity of being able to earn their living.

According to documents sent by the CSN to La Presse, the CSSMI sent a note at the end of January to all members of its staff recalling the new legal obligations governing the wearing of religious signs, following the adoption of Bill 94, on October 30th….

2026/02/23 2 Comments

Reality check:

…But Mr. Roberge said police are reluctant to act when people use prayer as a form of protest, for fear of being seen as infringing on their Charter rights. “The guidelines are not clear enough in situations involving religious demonstrations,” he told the committee. The minister declined an interview request.

The scope of the new legislation is wide-ranging. In addition to tackling public prayer, it would extend the province’s workplace ban on religious symbols to anyone working in daycares, colleges, universities and private schools. Quebec’s original secularism law, which is now being challenged at the Supreme Court of Canada, banned religious symbols for some public-sector employees, including elementary and high school teachers, police officers and judges.

The new bill would also prohibit prayer and other religious practices in public institutions, effectively banning prayer rooms at Quebec colleges and universities.

Critics say the legislation is a thinly veiled attempt to exploit anti-Muslim sentiment for political gain. In a brief presented to the committee, the National Council of Canadian Muslims said Quebec Muslims “feel less and less that they belong” in the province.

Bishop Poisson said there’s no reason to treat religious demonstrations any differently from other public events. “We must be careful not to build a society where the laws prohibit everything except what is permitted,” he said.

“I want to live in a country where everything is permitted except what is prohibited. There’s a big difference.”

Source: Quebec’s bid to limit public prayer felt in far-flung parts of the province

2026/02/20 2 Comments

Clear message by PM Albanese:

…Former Islamic State fighters from multiple countries, their wives and children have been detained in camps since the militant group lost control of its territory in Syria in 2019. Though defeated, the group still has sleeper cells that carry out deadly attacks in both Syria and Iraq.

Australian governments have repatriated Australian women and children from Syrian detention camps on two occasions. Other Australians have also returned without government assistance.

Australia’s Prime Minister Anthony Albanese on Wednesday reiterated his position announced a day earlier that his government would not help repatriate the latest group.

“These are people who chose to go overseas to align themselves with an ideology which is the caliphate, which is a brutal, reactionary ideology and that seeks to undermine and destroy our way of life,” Albanese told reporters.

He was referring to the militants’ capture of wide swaths of land more than a decade ago that stretched across Syria and Iraq, territory where IS established its so-called caliphate. Jihadis from foreign countries traveled to Syria at the time to join the IS. Over the years, they had families and raised children there.

“We are doing nothing to repatriate or to assist these people. I think it’s unfortunate that children are caught up in this, that’s not their decision, but it’s the decision of their parents or their mother,” Albanese added.

Source: Australia bans a citizen with alleged IS links from returning from Syria

2026/02/18 2 Comments

Not sure how practical or implementable it is, and existing prevention programs have a mixed record, but focus on behaviours, rather than beliefs is appropriate:

….A practical National Polarization Metrics model

Canada does not need a new bureaucracy. It needs a light-touch doctrine that makes prevention routine. A “National Polarization Metrics” model would use behavioural indicators that are measurable and non-partisan, focusing on coercive targeting and intimidation rather than beliefs: repeated harassment aimed at identifiable groups; doxxing and coordinated pile-ons; credible threats; and violence-normalizing signalling that changes what peers believe is acceptable.

That doctrine should assign accountable ownership. Every campus and school board needs an escalation lead with a clear mandate to consistently log incidents, coordinate support and safety planning, quickly preserve evidence, and trigger referrals when thresholds are met.

Far from weakening civil liberties, this reduces arbitrary decision-making and makes outcomes less dependent on institutional mood.

It also requires routable handoffs. Educational settings should have a consistent pathway for when matters stay at the level of documentation and support, when they require municipal policing involvement, and when patterns suggest coordination or mobilization indicators that justify a threat-assessment channel. Canada’s National Strategy on Countering Radicalization to Violence frames early intervention as a national priority, but it leaves Canada without a single escalation ladder that is understood—end-to-end—across education systems, municipal police, and federal threat assessment.

Finally, evidence preservation must become doctrine. A standardized 24-72-hour capture-and-preserve practice—time-stamped collection, secure storage, minimal access logging, and a consistent referral format—would strengthen downstream deterrence without criminalizing student life….

Prevention must become doctrine, not late reaction

A pluralist society can withstand disagreement. What it cannot withstand is normalized intimidation combined with institutional paralysis—especially when digital ecosystems accelerate conflict faster than administrators, police, or courts can react. If Canada wants to confront its fault lines before they deepen, it must stop treating youth extremism as cultural weather and start treating it as a measurable pathway.

That means building the missing bridge: shared indicators, accountable ownership, rapid evidence preservation, and standardized handoffs. Not to stigmatize communities, and not to criminalize student life—but to ensure coercion and violence-normalizing signalling do not become the price of campus politics, or the prelude to community harm.

Daniel Robson is a Canadian independent journalist specializing in digital extremism, national security, and counterterrorism.

Source: Canada has a youth extremism problem it can’t continue to ignore

2026/02/18 Leave a comment

ICYMI:

…Demographics is not the only reason Quebec’s influence in Canada is and will be diminishing, unless the province’s politics undergo a substantive change. Quebecers have not voted to separate from Canada in a referendum, but they have separated in some of their attitudes. In the Trump era, belonging to Canada may matter as a shield against the American president’s nonsensical threats. But otherwise, “les Québécois” appear less interested in our nation’s evolution than ever in my lifetime.

Quebec political leaders invest little time in engaging with their counterparts in Ottawa and in provincial capitals, except when specific files require it. The result is that very few politicians across the country have a deep understanding of Quebec’s part in Canada’s diversity. Additionally, recruiting highly qualified French-speaking Quebecers to work in the federal government is a challenge often lamented in Ottawa.

Justin Trudeau appointed a Governor General who does not speak French, a choice that, in earlier decades, would have been criticized not only in Quebec. There is pressure, for instance from the Alberta Premier, to appoint Supreme Court justices who cannot speak one of our country’s two official languages (guess which language it is?). Because of this lack of leadership at the national level, and as a result of French Canada’s relative decline, fewer Canadians value official bilingualism as a plus for our nation. A 2024 Léger poll showed that bilingualism was seen as positive by 70 per cent of Quebecers but only 35 per cent of Canadians outside Quebec. The Prime Minister’s rosy reimagining of Canadian history has no effect on today’s worrisome reality.

The demographic trends at play in Quebec will not only diminish its political weight. Population stagnation and aging threaten the province’s economic growth and fiscal situation. According to the economists at Desjardins, “the sustainability of Quebec’s welfare state model could be challenged.” Quebec’s leaders and population will face serious challenges in the coming years; their contribution to the federation will be the least of their concerns.

Quebecers’ votes played a crucial part in Mark Carney’s election win last year. But such scenarios, where Quebec has a significant impact on the shape of Canada’s federal government, will become fewer and far between. Because of high immigration levels outside Quebec, Canada is changing fast; in 2050, it will comprise close to 49 million people, many of them recent immigrants with no knowledge of French and understandably little attachment to the country’s bilingual status.

Source: André Pratte: Quebec’s slow disappearance from federal politics

2026/02/18 2 Comments

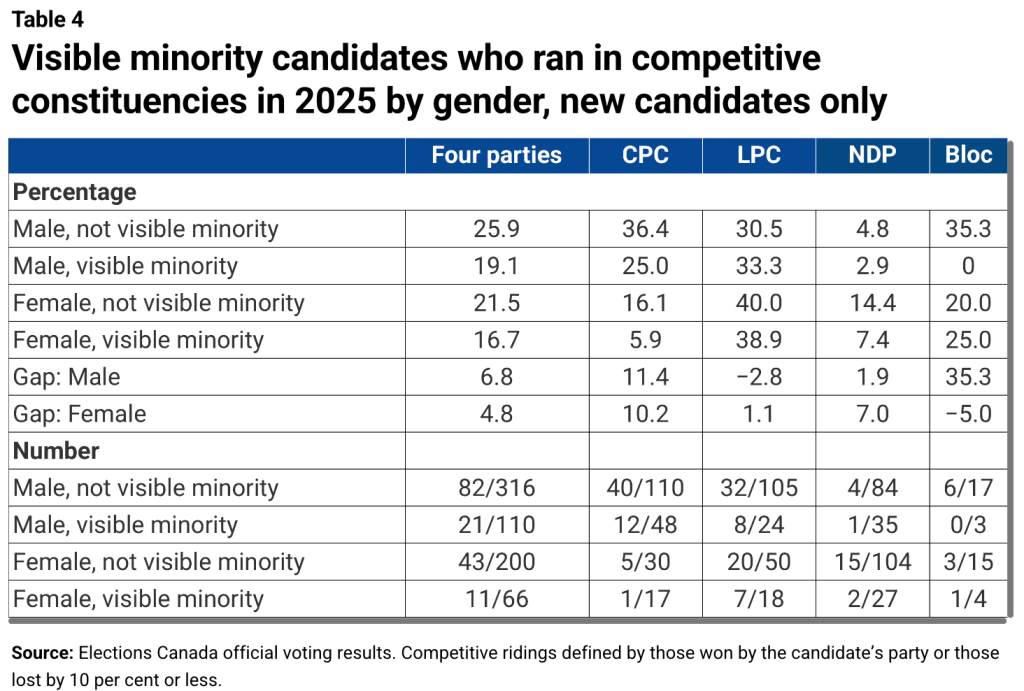

Our latest. Conclusion:

…In other words, party candidate selection incorporates affinity effects that give preference to visible minority candidates for all major parties in these ridings. Given this, it is less surprising that studies of election outcomes indicate that affinity effects are less important than “candidate competitiveness, Canada’s first past the post electoral system, and local context,” Elections Canada says, because those effects are effectively baked in at the candidate nomination stage.

This indicates positive discrimination for visible minority candidates in these ridings and the possible converse in ridings with lower numbers of visible minorities, largely rural ridings.

While one can make the crude case that nominating more visible minority women candidates would allow federal political parties to tick off two diversity boxes at once, the evidence indicates that this is not the case: women visible minority candidates do indeed have a higher percentage chance of being sacrificial lambs. This suggests they do experience biases in the political process across two fronts, as both women and visible minorities.

To encourage improved representation, the political parties should adopt a transparency approach similar to Senate Bill S-283 would require each party to provide annual information on the policies and programs they have enacted to increase the representation of designated groups (women, visible minorities, Indigenous Peoples and persons with disabilities).

This could be accomplished by the chief electoral officer administering a voluntary self-identification questionnaire to nominated candidates, thus allowing for post-election reporting on candidate and MP diversity.

Canada’s federal political parties may resist this transparency-based approach, but its use in federally regulated industries and the public service for close to 30 years has proven effective.

Source: Visible minority women are still sidelined in competitive ridings

2026/02/17 2 Comments

Good commentary:

…I unequivocally support Israel’s right to exist as a Jewish state, but I have also written repeatedly and critically about Israel’s tactics in its war on Gaza, which I believe have prolonged the conflict and created extraordinary and unnecessary human suffering.

Jewish lives aren’t more precious than Palestinian lives, and any form of advocacy for Israel that treats Palestinians as any less deserving of safety and security than Israelis isn’t just un-Christian; it’s anti-Christian. It directly contradicts the teachings of Scripture, which place Jews and Gentiles in a position of equality.

Second, internal Christian debates about whether the modern state of Israel is a fulfillment of biblical prophecy — as interesting as they can be — should be irrelevant to American foreign policy, which should be based both on American interests and American commitments to international justice and human rights.

But historic Christian antisemitism is rooted in a historic Christian argument, and it requires a specifically Christian argument in response.

Put in its most simple form, Christian antisemitism is rooted in two propositions — that Jews bear the guilt for Christ’s death (“Jews killed Jesus”), and that when the majority of Jews rejected Jesus (who was a Jew, as were all his early apostles), that God replaced his covenant with the children of Abraham with a new covenant with Christians. This idea of a new covenant that excludes the Jewish people is called “supersessionism” or “replacement theology.”

Put the two concepts together — “Jews killed Jesus” and “Christians are the chosen people now” — and you’ve got the recipe for more than 2,000 years of brutal, religiously motivated oppression.

Boller is a recent convert to Catholicism, and she — like Candace Owens — wields her newfound faith like a sword. But perhaps they both need to spend a little more time learning and a lot less time talking.

First, let’s put to rest the indefensible idea that “the Jews” killed Christ. As the Second Vatican Council taught, “The Jewish authorities and those who followed their lead pressed for the death of Christ; still, what happened in his passion cannot be charged against all the Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews of today.”

This isn’t a statement of high theological principle as much as basic common sense. Convicting an entire people, for all time, of the crimes of a few religious leaders is a moral monstrosity that runs counter to every tenet of Christian justice.

Second, Boller’s own church teaches that there is a deep bond between Christians and Jews. Last year, Robert P. George, a noted Catholic political philosopher at Princeton, wrote a powerful essayin Sapir, a Jewish journal of ideas, in which he described the relationship between the Jewish people and the Catholic Church as an “unbreakable covenant.”

As George writes, Pope Benedict XVI explicitly rejected the idea that the Jewish people “ceased to be the bearer of the promises of God.” Pope John Paul II said that the Catholic Church has “a relationship” with Judaism “which we do not have with any other religion.” He also said that Judaism is “intrinsic” and not “extrinsic” to Christianity, and that Jews were Christians’ “elder brothers” in the faith.

Indeed, paragraph 121 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church states that “The Old Testament is an indispensable part of Sacred Scripture. Its books are divinely inspired and retain a permanent value, for the Old Covenant has never been revoked.”

I don’t believe for a moment that the Catholic view is the only expression of Christian orthodoxy. I know quite a few Protestant and Catholic supersessionists who are not antisemitic, but I highlight the words of Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI because they starkly demonstrate the incompatibility of antisemitism with Christian orthodoxy.

But one doesn’t have to agree with Catholic teaching (or its Protestant analogues) to be fairly called a Zionist — a Christian Zionist, even — because one believes in the right of Israel to exist as a Jewish state.

The reason is rooted in Scripture’s commitment to equal dignity for all people, regardless of ethnicity, class or sex. As an extension of that commitment, no group of people should be subjected to abuse or persecution — much less genocide.

In this formulation, a so-called Christian Zionist would also likely be a Christian Kurdist (not a phrase you hear every day) or have a Christian commitment to Palestinian statehood. Kurds and Palestinians have also been historically oppressed, denied a home and deprived of the right to defend themselves.

In those circumstances, statehood isn’t a matter of fulfilling prophecies; it’s about safety and security. It’s about self-determination and the preservation of basic human rights. And if you think that can be done without supporting statehood, then I’d challenge you to consider the long and terrible historical record.

A consistent Christian Zionist would oppose both the heinous massacre of Jews on Oct. 7, 2023, and the aggressive, violent expansion of settlements in the West Bank. He would stand resolutely against Iranian efforts to exterminate the Jewish state and against any Israeli war crimes in Gaza.

Embracing the idea that the modern state of Israel is a direct fulfillment of biblical prophecies and therefore must be supported by the United States for theological reasons can lead us to dangerous places — to a belief, in essence, in permanent Israeli righteousness, no matter the nation’s conduct and no matter the character of its government.

But the opposite idea — that Christians have replaced the Jews in the eyes of God, and there is no longer any special purpose for Jews in God’s plan — has its own profound dangers. It creates a sense of righteousness in religious persecution, and it has caused untold suffering throughout human history.

The better Christian view rejects both dangerous extremes, recognizes the incalculable dignity and worth of every human being, and is Zionist in the sense that it believes that one of history’s most persecuted groups deserves a national home.

And since Christians have persecuted Jews so viciously in the past (and some still do today), we have a special responsibility to make amends, to repair the damage that the church has done. That begins by turning to the new Christian antisemites and shouting “No!” Ancient hatreds born from ancient heresies have no place in the church today.