Parkin, Triandafyllidou, Aytac: Newcomers to Canada are supportive of Indigenous Peoples and reconciliation

2022/06/22 Leave a comment

Particularly relevant on National Indigenous Peoples Day and current high levels of immigration:

Public education about Canada’s treatment of Indigenous Peoples is an important component of the process of reconciliation.

Knowing the history can better help citizens understand current challenges and equip them with the tools to work respectfully with Indigenous Peoples to build a better future, in keeping with the section on “education for reconciliation” in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report.

Much of this public education occurs in schools, through the media and even via discussions among friends and within families. But new immigrants to Canada might miss some of this socialization (depending on their age of arrival) because they’ll have less exposure to Canadian schools and media in their formative years.

This could affect their attitudes to Indigenous Peoples and support for the process of reconciliation itself. Given that one in five Canadians was born abroad, this would pose a significant political risk.

Alternatively, it’s possible that, despite less exposure to Canadian schools and media, immigrants might be more supportive of Indigenous Peoples because they could be more aware of the legacies of colonialism worldwide, more open to learn about their new country or more conscious of their responsibility as newcomers to learn Canadian history.

Supportive of Indigenous Peoples

The question of how immigrants perceive Indigenous Peoples in Canada, and vice versa, is therefore relevant but rarely explored.

But data from the Confederation of Tomorrow 2021 survey, conducted by the Environics Institute and including sufficiently large samples of both immigrants and Indigenous Peoples, allows us to examine these issues.

Specifically, we can explore perceptions of immigrants towards Indigenous Peoples and reconciliation, and look at responses to three questions:

- How familiar do you feel you are with the history of Indian Residential Schools in Canada?

- In your opinion, have governments in Canada gone too far or have they not gone far enough in trying to advance reconciliation with Indigenous peoples?

- Do you believe that individual Canadians do, or do not, have a role to play in efforts to bring about reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people?

The survey results generally show that, despite less familiarity or certainty about these issues among new immigrants compared to those born in Canada, they are more likely to support Indigenous Peoples.

Gap in knowledge

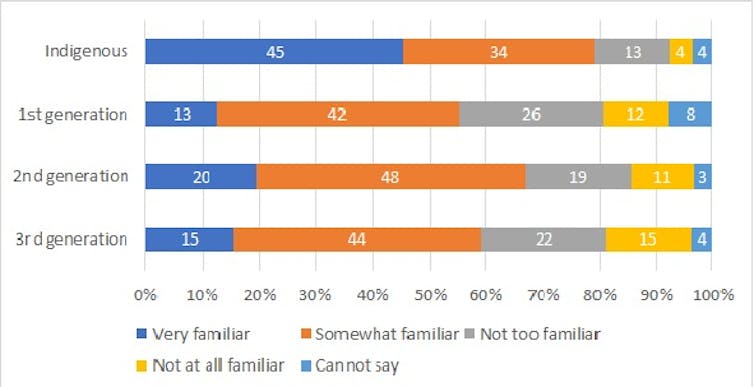

The survey shows a big gap between how familiar Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous people — both immigrants to Canada and non-immigrants — are with the history of Indian Residential schools.

The findings suggest first-generation immigrants are less likely than non-Indigenous Canadians to say they’re “very familiar” with this history, and are more likely to express no opinion.

These results indicate that first-generation immigrants don’t know as much as other Canadians about the history of Indian Schools in Canada. It is notable, however, that second-generation Canadians are more likely than third-generation Canadians to feel “very familiar” with the history of Indian Residential Schools.

This lesser familiarity among first-generation immigrants, however, does not translate into lower support for efforts to advance reconciliation.

Government response

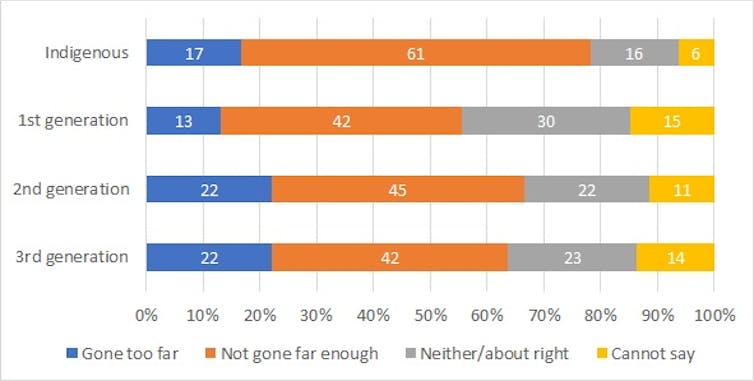

This support is evident when they were asked about whether governments have gone too far, or not far enough, to advance reconciliation.

The most striking difference — not surprisingly — is that Indigenous Peoples are much more likely than non-Indigenous Canadians to say that governments have failed to go far enough to advance reconciliation.

But first-generation immigrants are just as likely to hold this view than second- or third-generation Canadians. First-generation immigrants are also less likely to say that governments have gone too far in their efforts to promote reconciliation — a result that’s significant when controlling for education (which is an important step since first-generation immigrants are more likely to be university-educated than the rest of the population).

First-generation immigrants are also less likely to take a definitive position either way, and are more likely to say “neither” or “cannot say.”

The role of Canadians

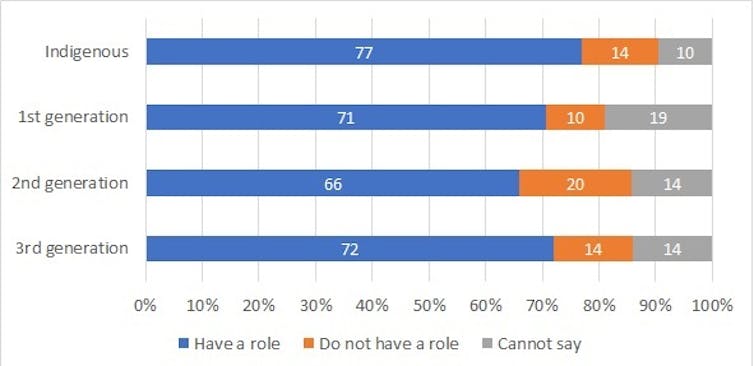

Similarly, Indigenous Peoples are unsurprisingly the most likely to say that individual Canadians have a role to play in reconciliation.

But first-generation immigrants are just as likely as second- or third-generation Canadians to hold this view (although first-generation immigrants are also more likely to have no opinion on this question).

These results are encouraging because they suggest that even if immigrants aren’t socialized in Canada at a young age, that’s not an obstacle to building understanding and support for reconciliation.

Indigenous support for immigration

Interestingly, the survey also allows us to explore the other side of the relationship between immigrants and Indigenous Peoples in Canada, namely support among Indigenous Peoples for immigration.

This is a potentially contentious issue. On the one hand, diverse sources of immigration in the post-Second World War period have already disrupted the narrative of Canada as a nation of two founding peoples (British and French). That in turn suggests a view of Canada that is not only multicultural but multi-national, and inclusive of Indigenous Peoples and nations.

In this sense, the interests of immigrants and Indigenous Peoples could be aligned. But at the same time, the ongoing arrival of newcomers can be seen as a continuation of the settler/colonization process.

Thoughts on immigration

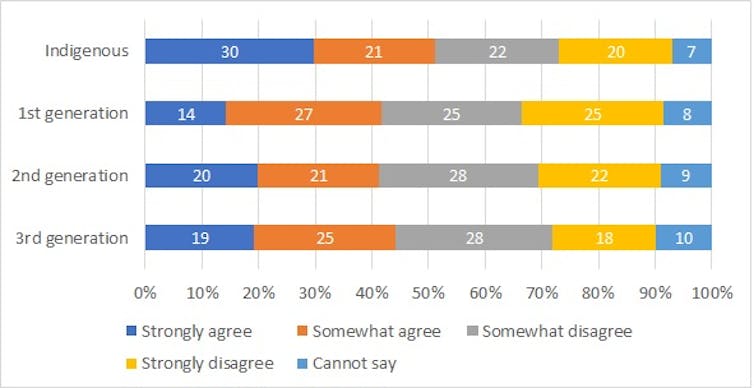

We can explore this issue by referring to a question in the survey asking Canadians whether they agree or disagree that “overall, there is too much immigration to Canada.”

The results show that there are significant differences in attitudes about immigration between the general population and Indigenous Peoples. Thirty per cent of Indigenous peoples “strongly agree” with the statement, the highest proportion among all groups.

However, this general difference about immigration levels is driven in large part by the difference in views between Indigenous Peoples and first-generation immigrants. While Indigenous Peoples, compared to first-generation immigrants, are more likely to strongly agree than strongly disagree that there is too much immigration to Canada, there are no statistically significant differences between Indigenous Peoples and second- or third-generation Canadians.

This suggests that the key factor influencing attitudes towards immigration might not be Indigenous identity, but being born in Canada.

Nonetheless, this finding is important because it’s a reminder to proponents of more immigration that they should be open to and engage with Indigenous Peoples’ perspectives on this issue. Immigration, as a policy objective, should be pursued with an eye on how it might be perceived by those who were displaced by the earlier arrival of settlers.

Source: Newcomers to Canada are supportive of Indigenous Peoples and reconciliation