The Daily — Aboriginal peoples in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census

2017/10/27 Leave a comment

The Daily’s summary of the Census findings regarding Indigenous peoples (assume StatsCan will eventually shift to that term):

Today, Statistics Canada is releasing its first results on First Nations people, Métis and Inuit from the 2016 Census of Population. Information about past and future releases from the census can be found through the 2016 Census Program release schedule.

Aboriginal peoples have lived in what is now Canada long before the arrival of the first European settlers. Indeed, the history of Canada would be incomplete without the stories of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit. The same is true of its future.

Past censuses have emphasized two key characteristics of the Aboriginal population: that Aboriginal peoples are both young in age and growing in number. The 2016 Census reaffirmed these trends. New data also reveal both the changing nature and the diversity of the First Nations, Métis and Inuit populations.

In 2016, there were 1,673,785 Aboriginal people in Canada, accounting for 4.9% of the total population. This was up from 3.8% in 2006 and 2.8% in 1996.

Since 2006, the Aboriginal population has grown by 42.5%—more than four times the growth rate of the non-Aboriginal population over the same period. According to population projections, the number of Aboriginal people will continue to grow quickly. In the next two decades, the Aboriginal population is likely to exceed 2.5 million persons.

Two main factors have contributed to the growing Aboriginal population: the first is natural growth, which includes increased life expectancy and relatively high fertility rates; the second factor relates to changes in self-reported identification. Put simply, more people are newly identifying as Aboriginal on the census—a continuation of a trend over time.

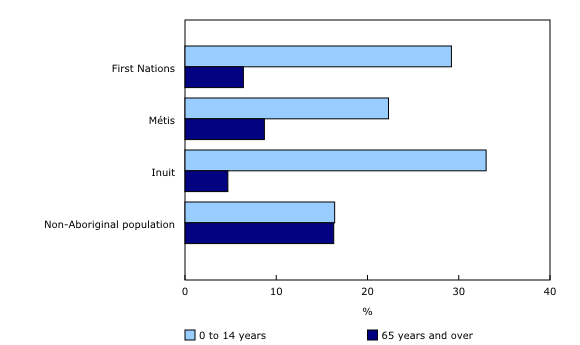

The First Nations, Métis and Inuit populations continue to be significantly younger than the non-Aboriginal population, with proportionally more children and youth and fewer seniors. However, they too are aging—in 2016, those 65 years of age and older accounted for a larger share of the Aboriginal population than in the past.

The data provide a portrait of the rich diversity of First Nations, Métis and Inuit populations. More than 70 Aboriginal languages were reported in the 2016 Census. Growth was observed in the Aboriginal population in urban areas, as well as First Nations people living on reserve and Inuit in Inuit Nunangat. Aboriginal children were more likely to live in a variety of family settings, such as multi-generational homes, where both parents and grandparents are present.

Rapid population growth among First Nations people, Métis and Inuit

The Aboriginal peoples of Canada—First Nations people, Métis and Inuit—include a diverse range of histories, cultures and languages.

The First Nations population—including both those who are registered or treaty Indians under the Indian Act and those who are not—grew by 39.3% from 2006 to reach 977,230 people in 2016.

The Métis population (587,545) had the largest increase of any of the groups over the 10-year span, rising 51.2% from 2006 to 2016.

The Inuit population (65,025) grew by 29.1% from 2006 to 2016.

The Aboriginal population is young but also aging

The Aboriginal population is young. The average age of the Aboriginal population was 32.1 years in 2016—almost a decade younger than the non-Aboriginal population (40.9 years).

As shown in the 2016 Census release on age and sex, seniors outnumbered children for the first time in Canada. This was not the case among Aboriginal peoples.

Around one-third of First Nations people (29.2%) were 14 years of age or younger in 2016—over four times the proportion of those 65 years of age and older (6.4%). For Métis, 22.3% of the population was 14 years of age or younger, compared with 8.7% who were 65 years of age and older. Among Inuit, one-third (33.0%) were 14 years of age or younger, while 4.7% were 65 years of age and older.

While the Aboriginal population is younger than the rest of the population in Canada, it is also aging. In 2006, 4.8% of the Aboriginal population was 65 years of age and older; by 2016, this proportion had risen to 7.3%. According to population projections, the proportion of the First Nations, Métis and Inuit populations 65 years of age and older could more than double by 2036.

First Nations population growing both on and off reserve

First Nations people possess a rich cultural heritage of diverse languages, histories and homelands. There are more than 600 unique First Nations/Indian Bands in Canada. The First Nations population includes those who are members of a First Nation/Indian Band and those who are not, as well as those with and without registered or treaty Indian status under the Indian Act.

The number of First Nations people with registered or treaty Indian status rose by 30.8% from 2006 to 2016. There were 744,855 First Nations people with registered or treaty Indian status in 2016, accounting for just over three-quarters (76.2%) of the First Nations population. The other 23.8%, which did not have registered or treaty Indian status, has grown by 75.1% since 2006 to 232,375 people in 2016.

Among the 744,855 First Nations people with registered or treaty Indian status, 44.2% lived on reserve in 2016, while the rest of the population lived off reserve. There was growth for both on reserve (+12.8%) and off reserve (+49.1%) First Nations populations from 2006 to 2016.

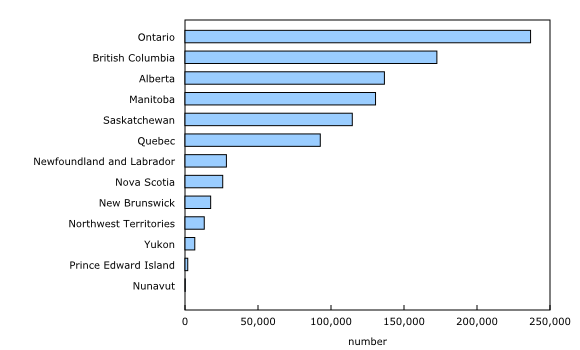

Over half of First Nations people live in the western provinces

The First Nations population was concentrated in the western provinces, with more than half of First Nations people living in British Columbia (17.7%), Alberta (14.0%), Manitoba (13.4%) and Saskatchewan (11.7%). By comparison, 30.3% of the non-Aboriginal population lived in the western provinces.

Almost one-quarter (24.2%) of the First Nations population lived in Ontario, the largest share among the provinces, while 9.5% lived in Quebec.

A further 7.5% of the First Nations population lived in the Atlantic provinces and 2.1% lived in the territories.

While First Nations people accounted for 2.8% of the total population of Canada, they accounted for one-tenth of the population in Saskatchewan (10.7%) and Manitoba (10.5%), and almost one-third of the population in the Northwest Territories (32.1%).

First Nations people accounted for a smaller share of the population in Quebec (1.2%), Ontario (1.8%) and the Atlantic provinces (3.2%).

First Nations population doubles in Atlantic Canada

While the First Nations population in the Atlantic provinces is relatively small (73,655 or 7.5% of the total First Nations population), it more than doubled (+101.6%) from 2006 to 2016. A significant part of this increase most likely stemmed from changes in self-reported identification, that is, people newly identifying as First Nations on the census.

Over this 10-year period, the First Nations population grew by 48.7% in Ontario and 37.5% in Quebec.

While the First Nations population grew at the slowest pace in Western Canada (+32.2%), the region saw the largest total increase in the First Nations population (+134,550) in Canada.

Ontario has the largest Métis population

Métis hold a unique cultural and historic place among the Aboriginal peoples in Canada, with distinct traditions, culture and language (Michif). Today, the Métis population is present in every province, territory and city in Canada.

There were 587,545 Métis in Canada in 2016, accounting for 1.7% of the total population.

Most (80.3%) of the Métis population lived in Ontario and the western provinces. For the first time, Ontario had the largest Métis population in Canada at 120,585, up 64.3% from 2006 and accounting for one-fifth (20.5%) of the total Métis population.

The Métis population grew by 32.9% in the western provinces from 2006 to 2016, to 351,020 people.

Alberta had the largest Métis population in the western provinces, accounting for 19.5% of the total Métis population. About the same number of Métis lived in Manitoba and British Columbia (15.2%), while Saskatchewan was home to 9.9% of the Métis population.

There were 69,360 Métis living in Quebec in 2016, accounting for 11.8% of the total Métis population. Meanwhile, 7.2% of the Métis population lived in the Atlantic provinces and 0.8% lived in the territories.

The Métis population grew at the fastest pace in Quebec (+149.2%) and the Atlantic provinces (+124.3%) from 2006 to 2016. Meanwhile, the Métis population grew by 64.3% in Ontario and by 32.9% in the western provinces. In the territories, the size of the Métis population was relatively unchanged from 10 years earlier.

Nearly two-thirds of Métis live in a metropolitan area

Of the three Aboriginal groups, Métis were the most likely to live in a city, with 62.6% living in a metropolitan area of at least 30,000 people.

There were eight metropolitan areas with a population of more than 10,000 Métis in 2016: Winnipeg, Edmonton, Vancouver, Calgary, Ottawa–Gatineau, Montréal, Toronto and Saskatoon. Combined, these areas accounted for just over one-third (34.0%) of the entire Métis population.

Winnipeg had the largest Métis population at 52,130 in 2016, up 28.0% from a decade earlier.

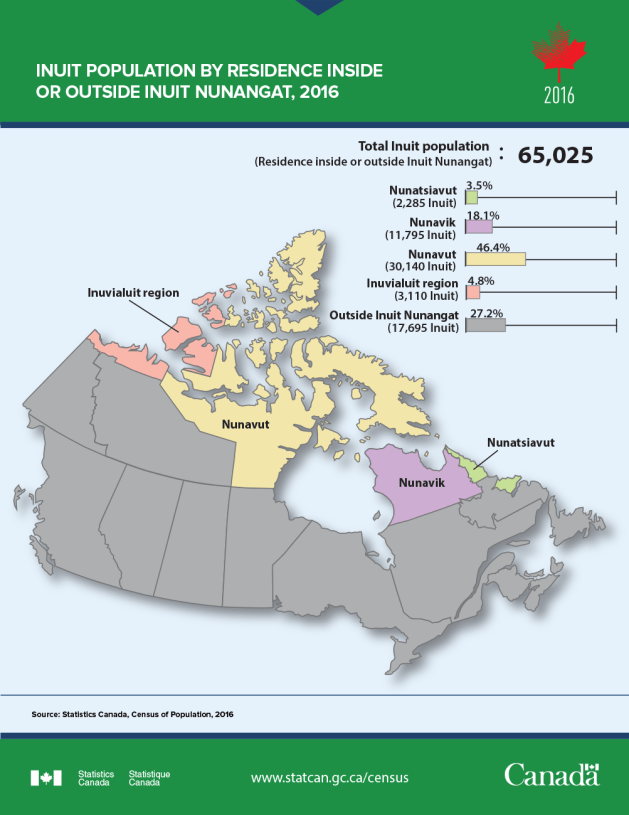

Almost three-quarters of Inuit live in Inuit Nunangat

Inuit are the original people of the North American Arctic. In Canada, Inuit have inhabited communities stretching from the westernmost Arctic to the eastern shores of Newfoundland and Labrador for uncounted generations. This area, known as Inuit Nunangat, refers not only to the land, but also to the surrounding water and ice, which Inuit consider to be integral to their culture and way of life. For more information, please visit the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami website.

There were 65,025 Inuit in Canada in 2016, up 29.1% from 2006. Close to three-quarters (72.8%) of Inuit lived in Inuit Nunangat.

Among Inuit in Inuit Nunangat, the majority (63.7% or 30,140) lived in Nunavut in 2016, while one-quarter (24.9%) lived in Nunavik, whose communities encircle the western, northern and northeastern coastlines of Quebec. Another 6.6% lived in the Inuvialuit region, which is located in the Western Arctic, while 4.8% lived in the communities of Nunatsiavut, along the northeastern coast of Newfoundland and Labrador.

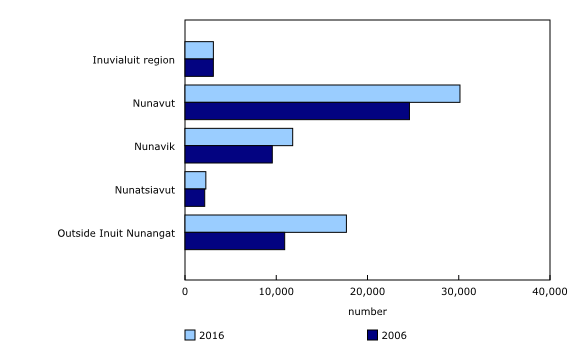

Inuit population growing inside and outside Inuit Nunangat

From 2006 to 2016, the Inuit population grew by 20.1% inside Inuit Nunangat. Outside of Inuit Nunangat, the Inuit population grew by 61.9%.

Among the four regions of Inuit Nunangat, the Inuit population grew the fastest in Nunavik (+23.3%) and Nunavut (+22.5%) over the 10-year period. In Nunatsiavut, the Inuit population grew by 6.0%, while in the Inuvialuit region the population was relatively unchanged.

Outside of Inuit Nunangat, the highest proportion of Inuit lived in the Atlantic provinces (30.6%). Most Inuit in the Atlantic provinces lived in Newfoundland and Labrador (23.5%), which accounted for almost one-quarter of the population of Inuit outside of Inuit Nunangat.

Over one in five Inuit (21.8%) outside of Inuit Nunangat lived in Ontario, while 28.7% lived in the western provinces. Just over 1in 10 (12.1%) lived in Quebec, while 6.8% lived in the Northwest Territories (not including the Inuvialuit region) and Yukon.

Many Inuit, outside of those living in Inuit Nunangat, lived in a city. Outside of Inuit Nunangat, 56.2% of Inuit lived in a metropolitan area of at least 30,000 people. Of Inuit living outside of Inuit Nunangat, the largest Inuit populations were in Ottawa–Gatineau (1,280), Edmonton (1,110) and Montréal (975).

The Aboriginal population living in metropolitan areas is growing

The increase in the urban population of Aboriginal peoples has been taking place for decades in Canada. This change has often been misunderstood simply as the movement by First Nations people away from reserves and into cities. In fact, the First Nations population continues to grow both on and off reserve.

Like the overall population growth of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit, the urbanization of Aboriginal peoples in Canada is due to multiple factors—including demographic growth, mobility and changing patterns of self-reported identity.

In 2016, 867,415 Aboriginal people lived in a metropolitan area of at least 30,000 people, accounting for over half (51.8%) of the total Aboriginal population. From 2006 to 2016, the number of Aboriginal people living in a metropolitan area of this size increased by 59.7%.

The census metropolitan areas (CMAs) of Winnipeg (92,810), Edmonton (76,205), Vancouver (61,460) and Toronto (46,315) had the largest Aboriginal populations. Among all CMAs, Aboriginal people accounted for the highest proportion of the population in Thunder Bay (12.7%), Winnipeg (12.2%) and Saskatoon (10.9%).

The Aboriginal population more than doubled in seven CMAs from 2006 to 2016: St. John’s, Halifax, Moncton, Québec, Saguenay, Sherbrooke and Barrie. Among all CMAs, the Aboriginal population grew the fastest in St. John’s (+237.3%), Halifax (+199.0%) and Moncton (+197.9%).

Over the same period, Aboriginal population growth was slowest in Regina (+26.4%), Winnipeg (+37.1%) and Saskatoon (+45.4%). However, even in Regina, where Aboriginal population growth was the slowest among all CMAs, the Aboriginal population grew at a faster pace than the non-Aboriginal population.

Aboriginal children more likely to live in a family with at least one grandparent

Understanding the characteristics of young children aged 0 to 4 years is important, as early childhood experiences influence not only current but also future well-being.

There were 145,645 Aboriginal children aged 0 to 4 years enumerated in the 2016 Census, accounting for 8.7% of the total Aboriginal population. Of this group, 60.1% lived with two parents.

Just over one-third (34.0%) of Aboriginal children aged 0 to 4 years lived with a lone parent. First Nations children aged 0 to 4 years (38.9%) were the most likely to live with a lone parent, followed by Métis (25.5%) and Inuit (26.5%) children in the same age group. However, many children living with a lone parent also lived with grandparent(s). In 2016, 10.5% of Aboriginal children aged 0 to 4 were living with a lone parent and grandparent(s).

About one in six (17.9%) Aboriginal children aged 0 to 4 lived with grandparent(s) in 2016, either with a parent present or without. Inuit children in this age group were most likely to live with grandparent(s) (22.8%), followed by First Nations (21.2%) and Métis (10.5%) children.

For more information on the family characteristics of young Aboriginal children, see the article “Diverse family characteristics of Aboriginal children aged 0 to 4“.

More than 70 Aboriginal languages reported

Language both shapes and is shaped by the culture to which it belongs. Aboriginal languages—grouped into 12 language families—have been central to the history of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit in Canada and continue to play a vital role to this day.

There is a great diversity of Aboriginal languages in Canada. There were more than 70 distinct Aboriginal languages reported in the 2016 Census, more than 30 of which had at least 500 speakers.

There were 260,550 Aboriginal people who could speak an Aboriginal language in 2016, up 3.1% from 2006.

In general, the number of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit who could speak an Aboriginal language was higher than the number with an Aboriginal mother tongue. This suggests that people are learning an Aboriginal language as a second language.

The article “The Aboriginal languages of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit” contains more information on the diversity of Aboriginal languages in Canada.

Source: The Daily — Aboriginal peoples in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census