Europe’s ageing societies require immigration to survive – and that means anti-immigration politics is here to stay

2017/12/22 1 Comment

An interesting analysis of the correlation between increased immigration and xenophobia in Europe. Not encouraging:

The era after WWII was mostly devoid of populist party influence. Instead, Europe was on the mend, and integration at the forefront of European if not global policy agendas. Integration ensured peace. The postwar-prosperity was phenomenal, productivity and social welfare programmes expanded rapidly. Given the changes in the past decades, in particular after the latest European expansion and Eurozone crisis, a new era is upon us.

Beginning in the 1970s in Western Europe, populism has risen yet again amidst the waves of immigration that began in the 1960s. The new populist parties are often unidimensional with explicit xenophobic, anti-immigrant positions. Their messages scapegoat non-white, non-native born persons; often with a diametric opposition to Muslims or Islamic culture. In Western European countries, anti-immigrant populist parties – sometimes labelled the ‘populist radical right’ or ‘neo-nationalists’ – expanded from below 5% of the national vote share in 1962 up to 13% by 2017, on average.

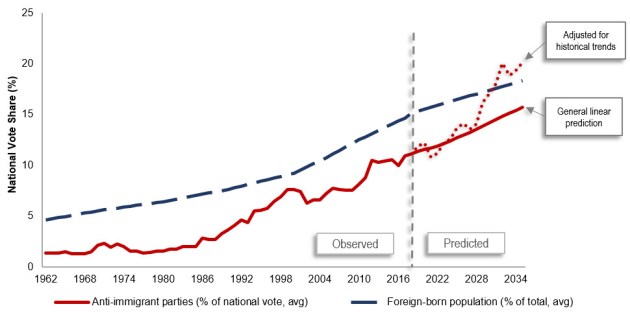

Figure 1: Immigrants and observed/predicted future support for anti-immigration parties in Western Europe (1962-2035)

Note: This chart is based on 17 countries: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Iceland, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK. Data from OECD, Global Bilateral Migration and ParlGov.

The vote share and percentage of foreign-born members of the population observed from 1962-2017 reveals a pattern. They rise in tandem. This is not a paradox of pooling Western European data. In each country on its own, the stock of foreign-born persons explains 50 to 97% of the variance in anti-immigrant party vote share (i.e., the range of correlation coefficients in 17 countries). This does not mean immigration causes anti-immigrant voting; however, social and political research explains why it is part of the causal process.

Immigration appears to be the only stable component of new populist parties and their limited policy victories. Thus far, new populist parties have successfully ushered in policies banning or criticising inter-ethnic marriage, the construction of Mosques, immigration flows and the human right to asylum (to name a few). Meanwhile, the UK voted to leave the EU; the Social Democrats in Sweden, after bleeding votes to the Sweden Democrats, introduced bureaucratic regulations against immigration; and perhaps most dramatically, 12.7% of German voters voted for the AfD, which is now Germany’s third largest party.

This marks a new era. The post-war spring season of growth has turned to autumn, with a fall in votes for mainstream parties, falling GDP growth and a potential decline in human rights. Anti-immigration views and aggressive displays of national pride, which might once have been confined to private dinner table conversations, have now moved into the public sphere, on the streets, in the media, and in political debates. The 2014 launch of PEGIDA and the sudden growth of the AfD are evidence of this public sphere change in Germany, the last place on earth one expects to find populism. At least 5 million Germans lost their lives under populist leadership last time around, not to mention those from other countries. Once out in the open, history suggests that nationalism reproduces itself because individuals see the public sphere as a safe space for them to express, if not grow their dissatisfaction with society and politics.

This is particularly acute when rates of immigration are increasing. Immigration provides a tangible basis to support narratives among the media and social networks that then shape the perceptions and experiences of natives. This leads to an increased salience of group boundaries. The native population may feel threatened by immigrants geographically and economically, challenging both group and national identities. These feelings magnify when native populations face increasing risks to their social and material security, a situation that lower income workers have had to confront since the 1980s due to a combination of economic crises, stagnant wages and welfare state retrenchments. Thus, redrawing or redoubling group boundaries is an active response, a defence mechanism built on the belief that the group will prosper if other groups are marginalised. This belief then fuses with the rhetoric of anti-immigration parties. As Figure 1 shows, this effect is likely a function of the number of immigrants in wider society.

Figure 2: Ageing population figures and observed/predicted GDP growth in Western Europe (1962-2035)

Note: Observed and predicted data from the OECD for Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Iceland, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK.

And immigration must continue to increase. The ageing population in Western Europe demands services and resources that the native working-age population cannot provide. Figure 2 demonstrates conservative estimates of both population ageing and GDP growth stagnation until 2035 from the OECD. Today a country is lucky to have 3% growth on average. Using predictive multilevel modelling and these statistics, we can tentatively predict that anti-immigration populist parties will increase their vote share.

The most conservative prediction suggests that the vote share for such parties will cross 15% by 2035, as shown by the solid red line in Figure 1. However, the development of this support follows distinct phases. After an anti-immigration party enters the political arena and acquires support, the average time before it gains 5% of the national vote is 3.2 years (albeit with a large variance). After this 5% threshold is met, anti-immigration parties follow a trajectory of swift gains in the early phase (within 10 years of crossing the 5% mark), stability if not turbulence in the middle phase (up to 15 years) and then ultimately more gains in the mature phase (up to 30 years) as sown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Trajectory of national vote share for anti-immigration parties after crossing the 5% threshold

Note: The three country phases include the following countries: Phase (a) includes Austria, Switzerland, France, Belgium, Norway, Denmark, Italy, Sweden, the UK, Greece, Germany and the Netherlands. Phase (b) includes Austria, Switzerland, France, Belgium, Norway, Denmark and Italy. Phase (c) includes Austria, Switzerland, France, Belgium and Norway.

Using these phases as an alternative augmentation to statistical prediction, suddenly 15% turns into a 20% vote share by 2035, shown by the dotted red line in Figure 1 after 2017. In most if not all countries, 20% of the national vote would put an anti-immigration party in second place and make it a serious contender as a coalition partner, as seen in Austria’s recent election.

Even with UKIP gaining much lower levels of support than this, the UK opted for a drastic undermining of European integration with its vote for Brexit. Meanwhile in other countries, support of between 5 and 25% of the vote for anti-immigration parties has coincided with more restrictive asylum rules or bureaucratic practices being put in place in Austria, Sweden, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands and Switzerland in recent years. A 20% vote share for anti-immigration parties would equate to a roughly 5-10% increase in the overall level of support for these parties in Western Europe. Moreover, if nationalist policies undermine international actors such as the EU or international frameworks such as the Geneva Convention, supranational arbitration will become increasingly difficult as states come into competition with one another.

How likely are these estimates? Nothing is certain and exogenous shocks are commonplace. Yet demographic science suggests that increased labour force participation, higher contributions from workers and employers, and lower benefits provided to retirees would be inevitable without an increase in immigration. In hyper-ageing societies such as Germany, the necessary increase would equate to a population where as many as 60% or more of citizens are foreign-born. Using these drastic estimates, the models outlined above also predict a 20% foreign-born population by 2035. Either way, the suggestion that support for anti-immigration parties will reach 15% on average by 2035 is potentially conservative, and 20% support is entirely possible.

Populism rises and falls in its myriad variants, but the explicitly anti-immigration version is likely here to stay. This carries additional baggage, as anti-immigration parties take aim at European integration while sometimes allying themselves with neoliberalism as both are in opposition to ‘the establishment’. These parties are not normally anti-democracy, but their authoritarian tendencies, their lack of coherent economic or educational policy and their willingness to foster division are all symptoms of the new season Europe is now entering: a European fall.