The rich world revolts against sky-high immigration

2024/07/24 Leave a comment

The Economist’s take but ignores likely impact of AI and automation in many sectors:

Immigrants are increasingly unwelcome. Over half of Americans favour “deporting all immigrants living in the us illegally back to their home country”, up from a third in 2016. Just 10% of Australians favour more immigration, a sharp fall from a few years ago. Sir Keir Starmer, Britain’s new centre-left prime minister, wants Britain to be “less reliant on migration by training more uk workers”. Anthony Albanese, Australia’s slightly longer-serving centre-left prime minister, recently said his country’s migration system “wasn’t working properly” and wants to cut net migration in half. And that is before you get to Donald Trump, who pledges mass deportations if he wins America’s presidential election—an example populist parties across Europe hope to follow.

It is not just words either. Australia, Britain and Canada are cracking down on “degree mill” universities offering courses that allow in people whose true intention is to work. This year Canada hopes to reduce the number of study permits by a third. Other countries are making it harder for migrants to bring family with them. Last month President Joe Biden announced measures to bar those who unlawfully cross America’s southern border from receiving asylum. In France President Emmanuel Macron wants to expedite deportations; Germany is enacting similar plans. More extreme restrictions could be on their way. After all, Mr Trump’s plans imply the removal of perhaps 7.5m people. What will this crackdown mean for economies across the rich world?

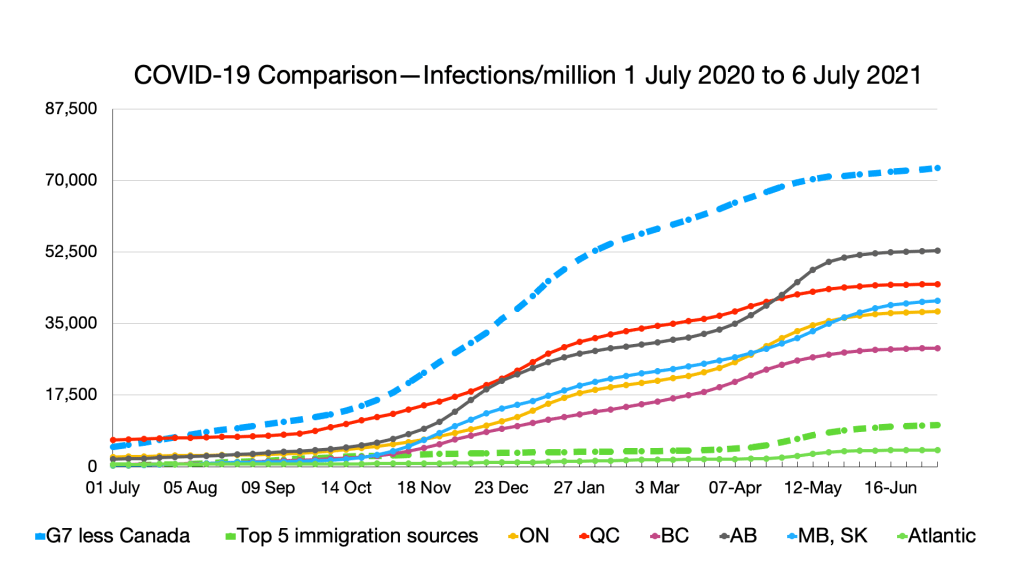

The change of approach follows a period of sky-high immigration. In the past three years 15m people have moved to rich countries, the biggest surge in modern history (see chart 1). Last year more than 3m people migrated to America on net, 1.3m went to Canada and about 700,000 turned up in Britain. The arrivals are from all over, including hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians fleeing war and also millions from India and sub-Saharan Africa.

Now there are signs the boom may be coming to an end. Net migration to Canada has nearly halved from its recent peak, while in New Zealand it is falling sharply. The rich world has fewer job vacancies than before, giving potential migrants less incentive to move, and the flood of refugees from Ukraine has slowed to a trickle. New anti-migrant measures are also starting to play a part. In the eu the number of third-country nationals who were returned to their home country, following an order to leave, has risen by 50% over the past two years. In the first quarter of 2024 “enforced returns” from Britain rose by 50% year on year. Illegal crossings at America’s southern border recently fell to a three-year low.

Some anti-immigration measures, especially large-scale deportations, could prove immensely damaging to economies. When Canada ramped up deportations during the Depression, it came at a large fiscal cost and clogged the ports. In 1972 the Ugandan government expelled thousands of people of Asian descent, whom it accused of profiteering. “There are virtually no African entrepreneurs left to take over the commerce,” a confidential cia memo reported in 1972, which also noted that it had become impossible to get a haircut in Kampala as all the barbers had shut.

Those close to Mr Trump argue that “Operation Wetback”—Dwight Eisenhower’s derogatorily named policy in the 1950s which expelled thousands of undocumented Mexicans—shows mass deportations can work without ill effect. True, the period was one of strong economic growth, and inflation remained low. Yet the comparison is misleading. During the 1950s legal Mexican immigration to America sharply rose, rather than fell. There is little doubt that Mr Trump’s proposal would cause economic chaos, as entire industries would be forced to find new staff. Warwick McKibbin of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, a think-tank, reckons that in the unlikely event that Mr Trump successfully deported 7.5m people, American gdp would fall by 12% cumulatively over three years.

There is greater uncertainty about the effects of more moderate anti-immigration policies, even if they are still likely to be damaging. In the short term, efforts to bring down sky-high migration would probably reduce inflation in the housing market. Research by Goldman Sachs, a bank, suggests that in Australia each 100,000 decline in annual net migration reduces rents by about 1%. As migration to Britain has slowed in recent months, so has the pace of rent rises (other factors are playing a role, too). In time, though, falling migration would probably push up other inflation. As labour supply declined, wages might grow faster than otherwise, raising the price of services such as hospitality.

A clampdown would also benefit gdp per person—the yardstick by which economists usually assess living standards. As immigration surged in 2022 and 2023, gdp per person in Britain fell. It has tumbled in Germany. In Canada it remains nearly 4% off its high in 2022. This has happened in part because the latest arrivals are on average less skilled than the resident population, meaning that they cannot command high salaries. Although this is a mechanical effect, rather than an actual hit to natives’ living standards, reducing immigration could stop the slide in the short term.

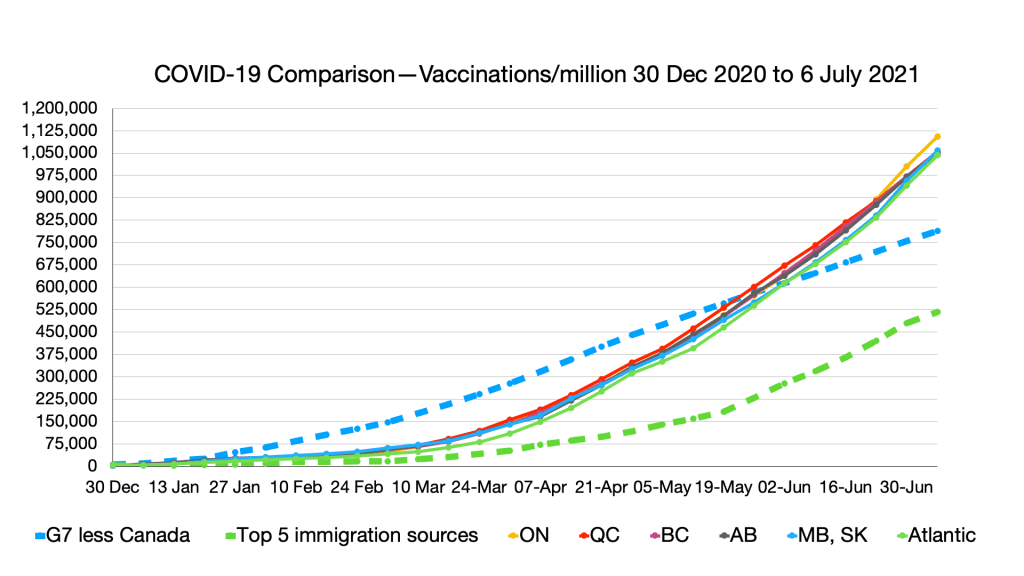

But it would do so with long-term costs. The new arrivals are finding jobs. Although for decades immigrants to Britain were less likely than natives to work, for the first time ever this is no longer true (see chart 2). The employment rate of migrants in Europe is the same as that for natives. Immigrants in America have long been likelier to work than people born in the country, and in recent months the gap has widened. Cracking down on migration risks provoking the re-emergence of labour shortages that plagued rich economies in 2021 and 2022, and which drag on gdp per person by creating inefficiencies. In the long term, immigration also allows for more specialisation in the labour force.

Crucially, the new arrivals often work in unglamorous, poorly paid but nonetheless vital industries, including construction and health care. From 2019 to 2023 the number of foreign-born people in America’s construction workforce rose sharply, even as the number of native builders fell. In Norway the number of foreign workers employed in health care has jumped by 20% since the covid-19 pandemic. The number of doctors working in Ireland but who trained elsewhere is up by 28%. During the same period the number of Chinese staff in Britain’s struggling National Health Service has doubled, while the number of Kenyans tripled.

Over time rich countries, which have ageing populations, will need more workers who are young and keen to work. This is because few politicians are talking about measures such as drastically raising the retirement age or how to make health care much more efficient. Although cracking down on new arrivals may buy politicians support for now, economic logic means the stance will be a nightmare to maintain.