Sunshine lists have helped narrow the gender pay gap, but Ottawa won’t commit to one

2021/05/18 Leave a comment

While I understand the attractiveness of sunshine lists, I find this places too much emphasis on the individuals rather than systemic trends and gaps.

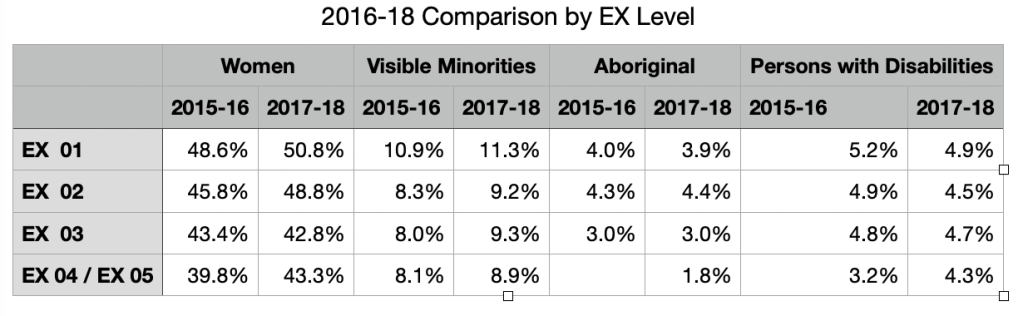

There is a wealth of government employment equity data for the four groups – women, visible minorities, Indigenous peoples and PwD – that can be disaggregated by occupational level. For example, an earlier analysis I did with TBS data:

While situations are different in universities, crown corporations and the like, where individual salary differences can be greater, in the federal public service it is the group and level that determine salaries, not individual negotiations. It would however, be useful for someone to request anonymized EX performance pay data to see if any significant gender and other differences:

The federal government does not release an annual “sunshine list” – a document outlining the name, compensation and often job title of its high-earning employees – unlike almost every province. And the Trudeau government has no plans to change this practice.

The Globe and Mail asked Treasury Board President Jean-Yves Duclos if the Liberals, who ran on a platform of government transparency and gender equity in 2015, would consider passing legislation on public-sector salary disclosure. Spokesman Martin Potvin replied that the board is “not currently working on any changes to how it reports” employee compensation.

This is despite years of feedback from equity advocates and researchers, who say sunshine laws have helped narrow the gender wage gap, as well as pressure from stakeholder groups concerned about a lack of transparency.

Beyond the issue of taxpayer accountability, sunshine laws around the country have revealed inequities in hiring practices, promotion and compensation.

For example, Anita Kozyrskyj, a professor in the department of pediatrics at the University of Alberta, was part of a group of female professors who used the university’s disclosure list to expose pay inequities within the faculty of medicine and dentistry. The academics found a $5,000 gender wage gap after accounting for factors such as rank and years of experience.

“[It] would not have been possible had we not had the sunshine list,” said Prof. Kozyrskyj, who learned she personally was making about $20,000 less than her equivalent male peers. (A similar report by academics at the University of Alberta used the sunshine list to reveal pay and representation gaps between men and women professors, as well as white and racialized faculty.)

Other research, such as a study from economists at the University of Toronto that examined the impact of sunshine laws on gender pay imbalances in academia, suggests disclosure leads to reduced inequities.

“The gender pay gap, in general, has been shrinking over time, and these laws have accounted for about 30 to 40 per cent of the closure since these laws were passed,” said one of the authors, Yosh Halberstam.

Universities that were unionized showed the clearest improvement, he added, suggesting progress requires both a mechanism to expose inequities, as well as a framework for staff to advocate for themselves.

Since January, The Globe has been publishing a series called the Power Gap, which looks at gender imbalances in the modern work force. By collecting sunshine lists from hundreds of employers across the country, the project produced an unprecedented look at where women stand within vital public institutions.

The data revealed how women’s careers are stalling out in mid-level management and how, on average, women made less than comparable male colleagues. But The Globe could not analyze federal employees, includingthose who work for the RCMP, public health, the Canada Revenue Agency or for federal Crown corporations – such as the Bank of Canada or Via Rail Canada – because the information is not available.

The Canadian Taxpayers Federation has been calling for Ottawa to introduce sunshine legislation for many years. “I think it’s a very simple transparency argument. There’s no reason that – if [almost] all the provinces are doing it, the federal government shouldn’t follow suit,” said Aaron Wudrick, the federal director of the organization.

The federation’s interest in the issue is centred around taxpayer accountability, which was then-premier Mike Harris’s motivation when his Progressive Conservative government passed Ontario’s sunshine law in 1996.

Other provinces followed suit over the past quarter century. Sunshine laws require government-owned or funded entities – such as schools and universities, Crown corporations, hospitals, the core public service and usually municipalities – to release data for all employees who earn more than a certain threshold, usually six figures. Today, every Canadian jurisdiction except Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, the territories and the federal government requires some form of disclosure for top earners. (In Quebec, only senior managers are subject to compensation disclosure.)

These lists are not without controversy. Politically, they have been used to shame well-compensated civil servants. But in daily practice, they are a vital tool of information for women and other equity-seeking groups.

Lorna Turnbull, a feminist legal scholar and law professor at the University of Manitoba, has spent decades studying and writing about the legislative attempts from government to narrow the economic inequality between men and women. A common thread in her research has been that laws alone are not enough to protect against discrimination. For example, it’s been illegal for decades to pay equally qualified men and women different salaries for the same job because of their gender, but it still happens.

In 2011, she encountered her own real-life example. Prof. Turnbull competed for – and won – the position of dean in the faculty of law. She was to be the first woman to hold that position in the school’s nearly 100-year history. But when discussions turned to salary, Prof. Turnbull realized she was being offered less than her male predecessors.

“I was able to discover this because Manitoba has a sunshine list,” she said. Prof. Turnbull used intel from the disclosure list to negotiate a higher salary. She served as the university’s dean of law until 2016.

Prof. Turnbull said modern-day discrimination is very rarely the kind of overt, easy-to-spot bias that was typical decades ago when governments began passing anti-discrimination laws. Without access to the hard numbers, women and other marginalized groups might never know they’re not being properly paid.

Sarah Kaplan, director of the Institute for Gender and the Economy at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, said sunshine lists are not without drawbacks, but on the whole they are useful.

“The downside is that if you are on the sunshine list and you can see that others of your peers are paid more than you, it can be very demotivating. Often, there is little possibility to negotiate pay adjustments once you are in the job,” she said. “But over all, the transparency can increase pressure for long-term change, such as promoting more women to the higher-paying roles and paying women more fairly when they are hired.”

The most recent province to pass sunshine legislation is Newfoundland and Labrador, after efforts from former St. John’s Telegram reporter James McLeod.

In 2015, the Progressive Conservative government promised to introduce salary-disclosure legislation, but after it lost power, the Liberals were indecisive about doing the same, Mr. McLeod says.

“I thought, if the government won’t do a sunshine list, I’ll do it myself.”

Mr. McLeod filed freedom of information requests with large public agencies and the issue ultimately ended up in court. With public pressure building, the government passed sunshine legislation on its own in 2016. (Also, Mr. McLeod’s case won on appeal.)

Gordon Scott Campbell, an information and privacy lawyer at Aubry Campbell MacLean, said one advantage that Mr. McLeod’s case had is Newfoundland’s freedom of information legislation actually states the public is entitled to know a civil servant’s salary. The federal act, on the other hand, states the public is only entitled to a salary range. As a result, it would almost certainly require a legislative change to release specific salary amounts.

Mr. Campbell said there is always tension between access and privacy.

“Privacy legislation seeks to strongly protect Canadian privacy … access-to-information legislation seeks to broadly free government information,” he said. “I think most Canadians would support [both]. So it’s a balance.”