Dave Snow: The federal government is spending millions on equity, diversity, and inclusion research

2024/04/03 Leave a comment

Informative data-based analysis of SSHRC funding for its Race, Diversity and Gender Initiative, revealing an overtly ideological and activist social justice and equity agenda:

…A year before, SSHRC awarded $19.2 million in funding for 46 grants of up to $450,000 for its Race, Diversity, and Gender Initiative to create partnerships to study disadvantaged groups. The program description encouraged projects that seek to “achieve greater justice and equity,” and its list of “possible research topics” included questions such as “How can cisgender and straight masculinity be reinvented for a gender-equitable world?” and “Which mechanisms perpetuate White privilege and how can such privilege best be challenged?” The language used in these new grants denotes the clearest shift yet towards more activist priorities in federal research grant funding.

SSHRC data on EDI

To determine whether the “hard” EDI of social justice activism has had a real effect on the types of projects that received funding for SSHRC grants, I conducted a content analysis of the titles of 680 grants awarded under four programs between 2022-23, the latter two of which are explicitly EDI-focused:

- Insight Grants announced in 2023, which “support research excellence in the social sciences and humanities,” valued between $7,000 and $400,000 over five years. (504 total)

- Partnership Engage Grants announced in 2023, which provide short-term support for a partnership with a “single partner organization from the public, private or not-for-profit sector,” valued between $7,000 and $25,000 for one year. (100 total)

- Knowledge Synthesis Grants to study “Shifting Dynamics of Privilege and Marginalization” announced in 2023, valued at $30,000 for one year. (30 total)

- Race, Gender, and Diversity Initiative grants announced in 2022, which support partnerships “on issues relating to systemic racism and discrimination of underrepresented and disadvantaged groups,” valued at “up to $450,000” over three years. (46 total)

First, I categorized each grant recipient according to whether their project title was clearly adopting a critical activist perspective (if there was any uncertainty, it was categorized as “no”).

I then categorized each grant according to which EDI identity markers the projects covered—Indigenous Peoples, women/gender, LGBTQ+, race, and disability (including mental health).

As Table 1 shows, the contrast between the two “traditional” grants and the two new EDI-focused grants was striking. Fully one-third of grants in the Race, Gender, and Diversity initiative focused on Indigenous Peoples, and 30 percent mentioned race or racism (compared with 3 percent and 1 percent of the Insight Grants).

The disparity is especially pronounced when you compare the Race, Gender, and Diversity grants to the Insight Grants, where there was an 11-1 ratio in the proportion of grants awarded on the topic of Indigenous peoples (33 percent versus 3 percent). There was also a 30-1 ratio in the proportion of grants awarded on the topic of race (30 percent versus 1 percent).

It might seem obvious that the two EDI-focused grants produced so many recipients with explicitly activist titles (63 percent compared with 9 percent of traditional grants). Yet it didn’t need to be this way. Examples of non-activist titles of Race, Gender, and Diversity Initiative recipients included “Understanding Race and Racism in Immigration Detention” and “Open-Access Education Resources in Deaf Education Electronic Books as Pedagogy and Curriculum.” One can study marginalized communities without engaging in social justice activism.

However, most of the EDI-focused grants awarded left no doubt as to the type of research that would be undertaken. Choice titles included:

- “‘So what do we do now?’: Moving intersectionality from academic theory to recreation-based praxis” ($450,000 grant awarded)

- “Queering Leadership, Indigenizing Governance: Building Intersectional Pathways for Two Spirit, Trans, and Queer Communities to Lead Social and Institutional Change” ($446,000 grant awarded)

- “Carceral Intersections of Gender Identity, Sexual Orientation and Trans Experience in Confronting Anti-Black Racism and Structural Violence in the Prisoner Reentry Industrial Complex” ($400,075 grant awarded)

In addition to grant titles, I also examined SSHRC’s diversity data on grant recipients from “underrepresented groups” for all major grants in SSHRC’s own EDI dashboard. This included Insight Grants, Insight Development Grants, Partnership Grants, and Connection Grants contained in SSHRCs (diversity data for the two new EDI-focused grants described above were not available).

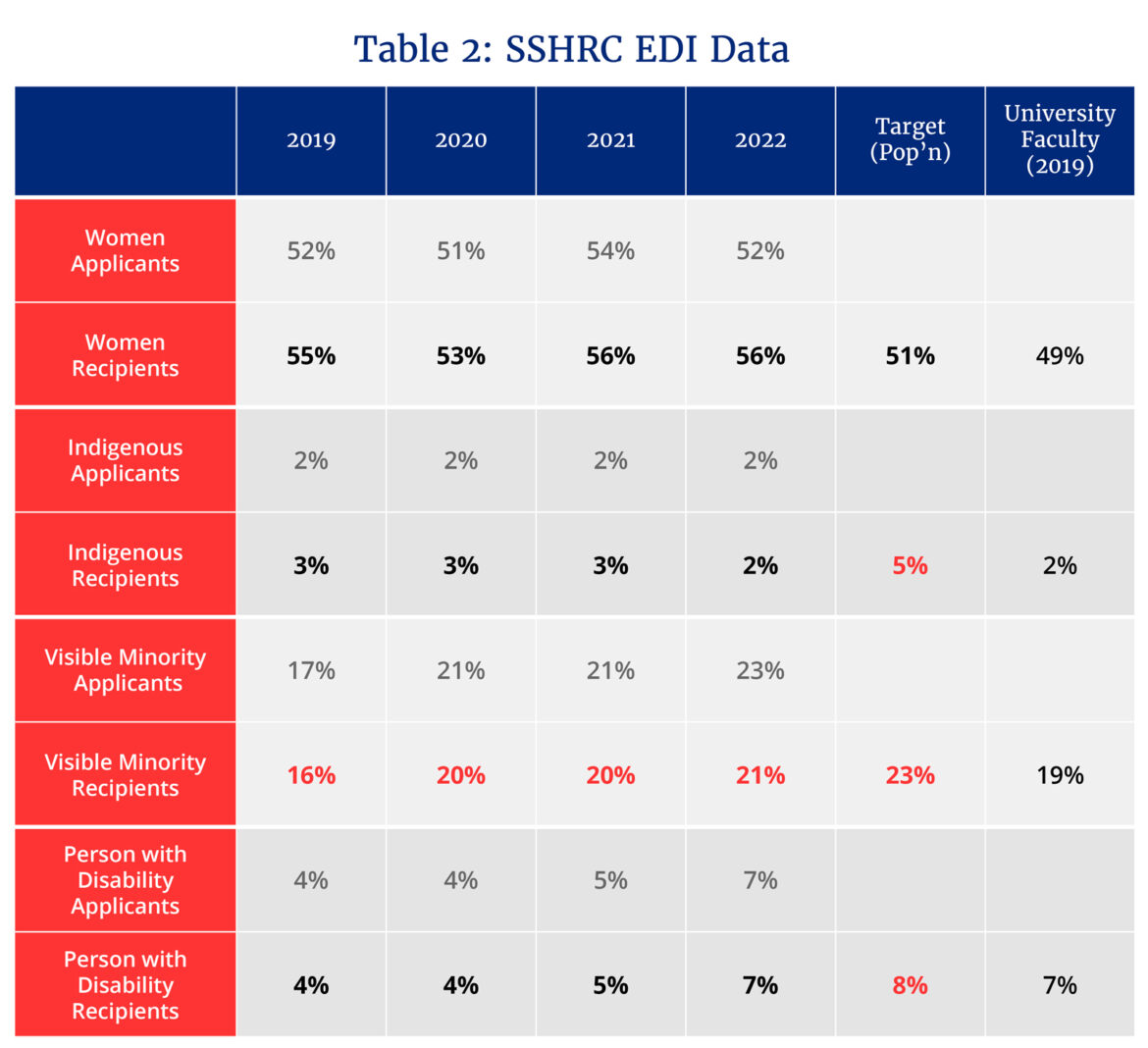

Table 2 provides these numbers alongside SSHRC’s equity targets for 2024/2025 and the groups’ proportion of Canadian university faculty as of 2019. Numbers in red show “under-performance” in the applicant-recipient ratio and SSHRC’s own targets.

Four things are notable. First, only one of SSHRC’s four target groups (visible minority applicants) has been underrepresented in terms of the applicant-recipient ratio. Second, while women are the only group who have exceeded SSHRC’s equity target, the percentage of recipients has been growing rapidly for visible minority applicants and persons with a disability. Third, no target group is underrepresented relative to its proportion of university faculty members, with women (56 percent of recipients) especially outperforming their faculty proportion (49 percent). Finally, Indigenous grant recipients (2 percent) are underrepresented relative to their proportion of the overall population (5 percent), but not relative to their proportion of university faculty members.

Damaging the pursuit of truth

The above analysis leads me to three broad conclusions. First, while the language of EDI has permeated SSHRC, the federal agency oscillates between the “soft” EDI of affirmative action and the “hard” EDI of critical social justice activism. Most of the time, SSHRC focuses on achieving “equity targets” and frames EDI as complementary to research excellence. However, SSHRC’s new EDI-themed grants explicitly adopt activist language, and it is little wonder that those awards have been dominated by activist projects.

Second, when it comes to the “soft” EDI of affirmative action, SSHRC’s policies are clearly having their intended effect for all groups except Indigenous Peoples. The number of grants awarded to women, visible minority applicants, and persons with a disability is rising. Grants are being awarded to members of these three groups at a proportion equal to or greater than their share of university faculty, and in the case of women, well above their share of the overall population. At this rate, it will soon be inaccurate for SSHRC to refer to “underrepresented groups” when it comes to prestigious national grants.

Finally, the “hard” EDI of critical social justice activism poses the biggest threat to SSHRC’s commitment to research excellence. While there are important critiques of the effects of “soft” EDI of affirmative action, it does not necessarily pose the same existential threat to research excellence. But the “hard” EDI of critical social justice activism is utterly incompatible with the objective pursuit of truth. One need only skim the titles of grants awarded under SSHRC’s two new EDI-focused initiatives to see how far they have strayed from the objective, empirical knowledge creation that we expect our national granting agencies to fund. Ironically, the more an award is pitched in terms of “diversity,” the less intellectually diverse the recipients seem to be. Thankfully, such activist research remains primarily confined to the new (and for now temporary) EDI-focused grants.

If the federal government wants universities to keep the public’s trust, it should avoid any future activist-themed grants and ensure that granting agencies eschew social justice priorities. Federal granting agencies using taxpayer dollars should be explicit that their primary commitment is to promote excellence via the creation and dissemination of objective, falsifiable research knowledge. The university is supposed to function as a system of knowledge production. Policies that openly tie research to activist political ends threaten to undermine that very system.

Source: Dave Snow: The federal government is spending millions on equity, diversity, and inclusion research